If you can't change the child perhaps you can change the school. Alternative schools for truants and offenders, called in New Zealand 'Activity Centres', are growing. Do they work? A case study.

LET SOMEONE ELSE DEAL WITH THEM

A study of students referred to an ‘Activity Centre’

By Kevin Kelly

Waikohu College

Introduction

IF CHILDREN are ‘unteachable’ in an ordinary school what can be done? Maybe they just refuse to work, maybe they regularly truant, maybe they are regularly disruptive, disobedient, violent, anti-social. The school doesn’t fit them, they don’t fit the school.

Psychological help will ‘cure’ some, but it takes time. Others have socially or culturally different lives which clash with the way schools are run. If you can’t change the child perhaps you can change the school. Or set up a special school for these special children.

That is the premise on which a system of alternative state schools for ‘unteachable’ secondary school students has been set up in New Zealand. They have been running (and expanding) for 16 years; they are called ‘Activity Centres’; each has one group of about 15 pupils; each is different and depends a lot on the personality of the teachers and the particular pupils who attend.

Do they work?

A Case Study

In 1982 Galloway and Barrett looked at two Activity Centres and reported on their success, or lack of it. From 1986 until 1988 I was Director of Awhina High School, which is an Activity Centre in the middle of the North Island, and I was therefore able to compare my findings with theirs.

The 18 students enrolled at Awhina during 1987 formed the basis of my study but I was also able to gain information from the parents of 16 of the students, six Educational Psychologists and Visiting Teachers, local secondary school Guidance Counsellors and of course the other staff at the Activity Centre.

I interviewed all these people and gathered information from questionnaires, checklists, suspension records, Educational Psychological Service Reports, referral documents and the ‘Brown Cards’ (standard school records). Documentation from students enrolled at the Activity Centre during 1986 but who had left was also examined and 56 students at a local co-educational High School were used as a comparison group. I looked back at the theoretical literature (centres with the same philosophy started in Britain in the 1960’s) and at other reports on such ‘withdrawal’ centres.

Basic data

1. In 1982 Maori students made up 50% of the students in the two Activity Centres Galloway and Barrett studied. At the time Maori made up 10% of the New Zealand population. In 1987 at Awhina High School there were 24 Maori students and one Pakeha. This percentage (96%) must be compared to the local school population which is 40% Maori.

2. In 1982 there were significantly more boys in Activity Centres. In 1987 the numbers were almost equal.

3. In 1982 the average age at which students arrived was 14 years, 9 months. In 1987 it was 14 years exactly.

4. The students give as the main reason for their being referred to the Centre, truancy or refusing to go to school. This fits with the Educational Psychologists’ reports. The other most important reasons were: being disruptive or aggressive, having difficulty with school work, school itself or a particular teacher.

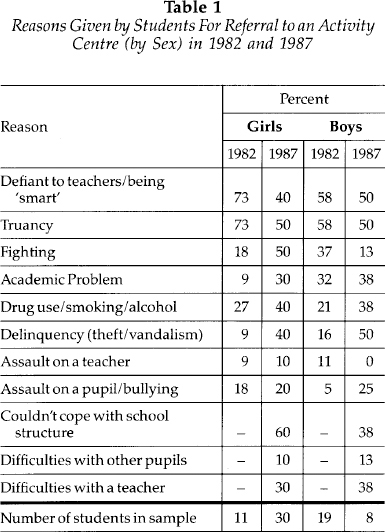

5. There have been changes in the reasons why girls and boys are referred. (see Table 1)

6. Pupils mention fighting more often than teachers or psychologists and the number of girls mentioning fighting has risen from 13% to 50% between 1982 and 1987. (See Table 1)

7. Those being referred to the Centres now are of lower IQ than those referred in 1982, on the basis of individual intelligence tests.

8. Reading: half the students in 1982 had a reading age three years below their chronological age. Seventeen of the 25 in 1987 (68%) were 3 years behind. The number of boys in this group had increased a little but the number of girls with these severe reading problems had more than doubled.

9. All the boys in my study had been in court, the 30 boys facing a total of 44 charges. Half the girls had been there too. Not all the girls had been in trouble with the police, but 10 had been to court for a total of 16 offences.

10. The primary agency that attempts to deal with family problems in New Zealand is the Social Welfare Department. The number of students whose families had been involved with the Department was less in 1987 than in 1982. A new programme for Maori families came into existence between these years called Maatua Whangai, and this may have relieved Social Welfare of some cases.

11. When asked to go through a list of problems which were facing them, the 1982 group averaged 73 problems, the 1987 group averaged 50 problems and a comparison group at a local high school averaged 36 problems. Self centred concerns were the most often mentioned, boy-girl problems the least.

12. Girls seem to have more troubles than boys. The boys at both the local high school and at the Centre saw themselves as having about the same number of problems but Centre girls were aware of many more problems than girls at the local school.

13. The Activity Centre boys and girls were most concerned about ‘self-centred problems’. This includes such topics as ‘not good-looking’, ‘having no friends or having difficulty making friends’, ‘can’t get along with people’, ‘too little chance to do what I want to do’, ‘wishing people liked me better’, fear of failure, getting into trouble, being picked on, no-one to tell troubles to, lack of self confidence.

Back in 1982 ‘school’ (boys) and ‘home and family’ (girls) had been the chief concerns. Boys at the local high school were more concerned about ‘school’. Girls at the local high school were most concerned about their ‘relations with other people.’

14. Half of the Activity Centre students in 1987 had either been in hospital or suffered a chronic illness. Though probably healthier than the Activity Centre students in 1982 they are not as healthy as most children.

15. Mental health was checked with a self-report questionnaire previously used in Britain and New Zealand. The results do not show psychological disorder but do point out if it is likely in the future. The possibility of the girls suffering clinically significant psychiatric disorder in the future is extremely high.

16. Only four out of 18 students were living with both parents. Back in 1982 twice as many lived with both parents. The size of families had dropped; the 1982 students most commonly had 4 brothers and sisters, the 1987 students had either 1 or 2. About two-thirds lived in houses the family owned and had been there 10 years. This is a more stable situation than in 1982.

17. One-third of the students didn’t know their father’s occupation, because he was no longer around. Of the rest only three fathers were unemployed. Only four of the 16 mothers were working, only one full time. Four mothers were solo mothers on benefits. Back in 1982 half the mothers worked.

18. Overwhelmingly, parents had left school with no qualifications, only one University Entrance qualification and one School Certificate had been gained.

19. Parents were very pleased their children were at the Activity Centre.

20. The majority of students at Awhina had been suspended from school. Suspension had been the rule in 1982 also. The number of boys and girls suspended is much the same. Of the five schools in the area, one – a Catholic school but integrated into the state system – referred no students to Awhina. The others contributed almost equally, one co-ed school indirectly because pupils suspended were first found places at other schools then suspended by their new school and referred to Awhina. Co-ed and single sex schools contributed equally.

21. The average stay at Awhina was 6.9 months. The longest stay was 14 months, the shortest 3 days. Girls stayed longer than boys. Children sent, not from school, but referred by the Social Welfare Department stayed very short periods – they were usually very delinquent or seriously emotionally disturbed.

22. On leaving the Activity Centre a few went on to further Social Welfare care, a few to work skills programmes, and one or two to other schools, drug rehabilitation, or a job. The largest number became unemployed.

Discussion

That Activity Centres are overwhelmingly Maori is well known and much agonised over. The changes needed to alter this situation are so huge that one could dispair. Possible solutions proposed include (i) changes in curriculum, (ii) changes in teaching style, (iii) changes in value systems, Maoris becoming more Pakeha, Pakehas becoming more Maori, (iv) changes in the whole schooling system, (v) changes in referral systems, (vi) changes in perceptions (Awhina soon became known as a Maori school), (vii) changes in economic wealth, jobs, prospects, etc. And so on.

It has become deliberate policy to try to keep the numbers of boys and girls accepted at Activity Centres about equal. However, it does appear that girls are more frequently suspended than they used to be. This may be a reflection of changes in girls’ behaviour or a comment on how teachers behave.

School pupils are coming to Activity Centres much younger than before. Are they coming into conflict with the school system younger, or is the very existence of the Activity Centre giving schools a chance to report disruptive behaviour earlier, and shuffle off their problems? A look at the suspension figures should show if schools are experiencing more trouble than before, but unfortunately the methods for recording who is suspended and why, are very inadequate. Only a few students who are suspended are referred to an Activity Centre, and even then the circumstances and reasons are not clearly recorded. On the whole, but without hard data, it appears that students are more unruly now, and become so at a younger age.

The most important reason given for referral to the Activity Centre is truancy. But that is a symptom rather than the reason. ‘Inability to get along with a particular teacher’ and ‘disruptive or aggressive’, the next most often given reasons, seem closer to the heart of the matter, but still beg the questions, ‘Why the clash?’, ‘Why the aggression?’ Both girls and boys mention fighting as a reason and 50% of the girls nowadays mention it – many more than boys (12%). This must be a change in society in general, as fighting amongst girls was very rare in the past.

The ability and reading tests point clearly to one of the reasons why the Activity Centre children are not in tune with the ordinary school system. That the Centres are now taking children who are less intellectually able and further behind in reading has strong messages for us, but they are difficult to sort out. Are more slow children getting to high school? That seems unlikely; we are 50 years beyond the New Zealand Proficiency exam which did keep slow children out of secondary school. Are the slow children now less docile than they were? Possibly. Are the sharper disruptive children now just disappearing and not getting to Activity Centres at all? Possibly. Are Activity Centres seen as a substitute for ‘slow-learner’ classes at ordinary schools? Quite likely. Problems with reading are not just an Activity Centre phenomenon. In 1987 in Rotorua Lakes High School 78% of the 13-year-olds had reading ages below 11 years.

It is not clear from the data why the 1987 Activity Centre students had been caught for more burglaries, shop lifting, and other criminal offences than the students in 1982. The number of girls offending has certainly jumped. The major difference immediately visible is that Maori gangs, such as the Mongrel Mob and Black Power, have gained prominence over the years. Many of the 1987 Activity Centre students considered themselves affiliated to a gang, gave a gang support, said they believed in their value system, and looked forward to membership of a gang.

The health figures show few problems for present day Activity Centre students, but girls still have more health problems than boys. It is also clear, from wider data, that Maori students have more problems than Pakeha. Farewell to the myth of the happy-go-lucky, poor-but-cheerful, family-stabilised, Maori! The psychological outlook for these young people is not good. They were highly aware of health problems so perhaps there is hope they will seek the right help, but where it is expensive, or buried in an unknown system, it is hard to get.

The number of students living in one-parent homes has increased. Living with one parent may be more satisfactory than living with two where there is violence or unhappiness or instability but lack of role models is a disadvantage, as are a lack of supervision, discipline or control, not to mention finance.

The data I have given on where the students went after leaving the Activity Centre cannot be taken as typical – it was too limited for generalisation. But the destinations, given the economic times and the children’s troubles, are not surprising.

What Next?

Knowing the multiple disadvantages these Activity Centre students have if I had some control of the country’s purse strings I would want answers to the following questions – and wish to see some action.

1. Why are Maori Children over-represented in Activity Centres?

2. Why are Maori children not remaining and achieving success in ordinary high schools?

3. The age students come in conflict with the school system is decreasing (9 months in 5 years). How can at-risk children be identified, and helped, well before crises are reached?

4. How can truancy be reduced? It is a symptom, and warning light. The underlying reasons for it must be addressed.

5. A Home and School Liaison staff member, not necessarily a teacher but someone persona grata with local families, would be a help to schools, the Social Welfare Department, and new helping agencies such as Maatua Whangai.

6. How can reading instruction be improved, early, to cut out a common trouble at school? A secondary school ‘reading recovery’ programme seems essential.

7. How can mathematics recovery be instituted also?

8. Alternative texts with sound ideas but easy reading should be written and published.

9. Alternative courses more suitable to children whose learning style is more visual and oral than literary should be set up.

10. Schools must be more responsive to teacher-pupil personality clashes which many Activity Centre students give as major reasons for their disruptive behaviour.

11. Similarly, schools can be more aware when subjects are becoming unpopular. What can they recommend be done about it?

12. Many Activity Centre students, especially those who are not intellectually quick would benefit from ‘work experience’ classes. How can more be set up? Such classes may be unlikely, given the present trend towards Mainstreaming, so how can adequate provision for these students be ensured. The new Special Needs equity funding may go’some way towards this end, but it remains to be seen.

13. Over one thousand students under the age of fifteen years are suspended indefinitely from New Zealand secondary schools each year. Only a small percentage are enrolled at an Activity Centre. Others are re-enrolled at another secondary school. However many others simply disappear. What happens to these students should be of major concern to education administrators and policy makers, especially. Their destinations should be known so that appropriate provision can be made. There is a need for urgent and detailed research into this problem.

14. More detailed information should be available about students who have been suspended for two or three days or have been suspended indefinitely. At present this information is not generally available. Whenever a student is suspended, information should be recorded in a common format in all secondary schools and the recording of this information should be mandatory. Such information should include: age, sex, ethnic group, detailed and specific reason for the suspension including background incidents which led to the crisis, number of times previously suspended, types of informal suspension used previously, previous action taken within the school and by whom, a copy of a recent education psychologist’s report if one is available or a copy of a report that was specifically requested for this purpose, alternative education placements considered, follow up action to be taken and a record of all those who were sent copies of this information and some verification that they received it.

Suspension is a drastic course of action with severe ramifications for the student and the family. It should not be taken without this information being available and a strict format followed.

15. Parents of suspended students should receive specific details of their right of appeal and clear instructions of how to go about it.

16. No student should be indefinitely suspended without first being seen by an educational psychologist and a report being made available to the committee making the decision.

17. Procedures must be put in place to ensure that the student is enrolled at a new school as soon as possible. Clear deadline dates must be in place and they must be enforceable. New Legislation makes this action the responsibility of the suspending school but is this entirely fair?

18. The scope and role of Activity Centres should be broadened. Rather than simply providing an education, they should be the focal point for intervention with a student in the widest sense. A Department of Social Welfare social worker, a Maatua Whangai worker or some such person should be attached to the Activity Centre for a least one day per week. They would be involved with the students and families who required assistance. In many cases the Activity Centre is the one place the students attend on a regular basis and as such it is a logical place to begin any intervention. At present much of the Activity Centre staff’s time is spent providing written and verbal information on their students for a variety of purposes.

19. Community health workers should regularly visit the Activity Centre and preferably should spend at least one day per week there. The physical and mental health of the students is not good and they are in need of regular attention. A Community health worker can readily organise appointments with health professionals and teach health education covering a wide range of topics. They can work with parents to see that treatments are followed and can offer health education advice to them as well.

20. An ‘At-Risk Index’ should be developed so that students can be identified at the earliest possible stage in their education and high-risk students can be closely observed. While this may be unpopular and certainly it would not be infallible, it would go some way towards ensuring that students are identified before it is too late. Such an ‘At-Risk Index’ would be complicated and difficult to produce but worthwhile.

21. Greater provision must be made within the secondary school (and primary) for disruptive or aggressive students. At the present time these students disrupt classes, causing stress for both the teacher and pupils. A range of options are available such as ‘time out’ or withdrawal rooms, resource units staffed by trained teachers, and alternative programmes. But such provisions require extra staffing and finance. Unless these become more freely available this problem will continue. Other solutions such as lowering the leaving age or making secondary education no longer compulsory are not viable. Altering social behaviour (promoting positive behaviour) is the best option but this would also require extra staffing, resources and finance.

22. The secondary school curriculum continues to be too inflexible to allow appropriate provision for students with special needs. Schools should identify the needs of their students, all their students, and adapt the curriculum to meet these needs. A school should be able to respond to the rapidly changing needs of their students quickly and in the most appropriate manner. It is not possible at the present time. The appointment of ‘Special Needs’ or Resource Teachers in some schools is a move in the right direction but it is still not enough to have a big impact. This approach needs to be expanded within schools and over all schools.

Notes

Kevin Kelly is a teacher at Waikohu College, Box 21, Te Karaka, New Zealand. The work from which this item is derived was for an MEd from Canterbury University. The full report can be requested on interloan from the Canterbury University Library, Christchurch, New Zealand.

The work of Galloway and Barrett can be found in

Galloway, D.M. and Barrett, C. (1982) Unmanageable Children? A Study of Recent Provision for Disruptive Pupils in the New Zealand Education System.

Other work on disruptive children can be found in

Galloway, D.M. (1981) Disruptive Pupils, set: Research Information for Teachers, No. 1, 1981, Item 6.

Galloway, D.M. (1980) Exclusion and Suspension from School, Trends in Education (ii), pp. 33-38.

Galloway, D.M. (1982) A Study of Pupils Suspended from School, British Journal of Educational Psychology, Vol. 52, pp. 205-212.

The checklist used for health measures can be found in

Mooney, R.L. and Gordon, L.U. (1950) Manual to the Mooney Problem Checklist, New York: Psychological Corporation.