Young children co-constructing stories with teachers

Amanda White, Shelley Stagg Peterson, and Emma Quigan

Children’s story experiences are foundational to their social, emotional, and communication development. Viewed through a sociocultural lens, variability in the ways children and teachers interact during stories across diverse learning contexts is expected. This article explores the social and cultural knowledge demonstrated by children of different ages as they co-construct meaning multimodally during stories with teachers across two early childhood educational settings, in Canada and New Zealand. Teachers’ gestures, gaze, questions, and verbal and non-verbal affirmations centred on themes, characters, and actions as they co-created stories with children. Teachers’ mediating roles and practices supported and sustained children’s embodied actions, languages, and cultures. Teacher–child stories shared in this article highlight the value of everyday stories as contexts for extending children’s learning, and the multimodal nature of story interactions underpinning the co-construction of meaning in early childhood education contexts.

Introduction

Story interactions between teachers and young children provide valuable opportunities for social, emotional, and cognitive learning and development (Reese, 2013; Schick & Melzi, 2010). Responsive, reciprocal, and multimodal story interactions in early childhood education (ECE) contexts have been found to extend children’s communicative and cultural understandings (Cremin et al., 2017). This article explores the contributions made by children of different ages and their teachers as they co-construct meaning during stories across two geographical locations, using varying combinations of modes to communicate meaning. Despite multiple points of difference across the two settings, we find common ground by identifying ways that children and teachers contributed multimodally to co-create stories. We focus specifically on children’s story roles and knowledge, as well as teachers’ efforts to support and extend child-led stories. Our research contributes to conversations about what it means for teachers to co-create stories with children in multimodal ways, illustrating what children and teachers might bring to those interactions within everyday moments of meaning, and using combinations of oral, auditory, gestural, tactile, visual, written, and spatial modes (Kalantzis et al., 2016).

We start by introducing ourselves and giving the background contexts through which this article arose. We then identify research questions and key literature and methods relating to this inquiry. In presenting findings from both settings, we employ two ways of demonstrating multimodal contributions of children and teachers during story interactions: one that foregrounds visual photos alongside written text descriptions of gesture and language during a storybook interaction, and the other that foregrounds written text to document gestures and language without visual photos during storytelling about personal family experiences. Finally, we discuss key themes and implications from both sets of findings.

The background context

We are part of a network of researchers brought together by the Marie Clay Research Centre at the University of Auckland, supported by a Royal Society New Zealand Catalyst Seeding grant, to share and build on one another’s research examining young children’s opportunities to learn through quality talk and interactions in their families and early childhood centres. Three international researchers joined 12 key researchers from Aotearoa New Zealand, including prominent Māori and Pacific scholars, who have contributed to New Zealand’s rich history of early childhood research. In this article, three members of this network—two New Zealand researchers and a Canadian researcher—collaborate. We draw upon pre-existing data generated before our initial meeting, acknowledging differences in our ECE curricular contexts, participants, methods, and presentation of findings across the two studies.

The New Zealand researchers share a prior background as speech-language therapists who were undertaking postgraduate (master’s and doctoral) research in education. Research reported in this study originates from the doctoral study focusing on multimodal story experiences of 1-year-old toddlers, within and across their family homes and ECE centres, in a culturally and linguistically diverse community of Aotearoa. In this article, we draw on data relating to multimodal interactions between two toddlers and their teacher in an ECE centre. Of central importance to this context is Te Whāriki, the national ECE curriculum, underpinned by kaupapa Māori and sociocultural theories (New Zealand Ministry of Education, 2017). Te Whāriki is a bicultural curriculum underpinned by principles of the Treaty of Waitangi where Māori people are recognised as tangata whenua, or Indigenous people of the land. As one strand of the curriculum, Mana reo/Communication includes the learning outcomes of children using non-verbal and verbal communication skills for a range of purposes and experiencing stories and symbols of their own and other cultures. Te reo Māori, the Indigenous language of Aotearoa New Zealand and an official national language, is one valued cultural resource and semiotic mode used in everyday social interactions in ECE settings.

Te Whāriki includes five areas of learning and development, as evident in the strands of Mana atua/Wellbeing, Mana whenua/Belonging, Mana tangata/Contribution, Mana reo/Communication, and Mana aotūroa/Exploration. Similarly, the document guiding kindergarten programmes in the Canadian province of Ontario (Ontario Ministry of Education, 2016) is play-based, with five developmental domains—social, emotional, communication/language, cognitive, and physical.

The Canadian researcher leads a 7-year partnership research project, Northern Oral language and Writing through Play (NOW Play), involving collaborative action research with kindergarten and primary teachers to develop play-based teaching and assessment approaches and tools supporting young children’s language and writing. Kindergarten teachers participating in this project were interested in developing an assessment tool to capture children’s language and narrative knowledge in personal stories. Tool development and the tool, itself, the Language and Nonverbal Communication Assessment (LNCA) are described elsewhere (Peterson et al., 2021).

The following questions guided our analysis of child–teacher story interactions:

1.What social and cultural knowledge about stories do children demonstrate as they co-construct stories with their teachers, and what communicative modes do they use?

2.What roles do teachers take in the co-construction of stories with young children?

We explore aspects of multimodal communication in teacher–child interactions from infancy through to school in New Zealand and in Canada.

Story development in infants and young children

Stories or narratives are “a way of making sense—of giving meaning to observable events by making connections between them” (Wells, 1986, p. xii). Children’s stories have been conceptualised linguistically as oral or written forms of meaning (see, for example, Schick & Melzi, 2010). Recent studies emphasise the embodied, visual, and non-linear ways that stories are co-constructed between young children and adults with ensembles of eye gaze, body movements, gestures, and spoken language adding to the rich landscape of stories in early childhood settings (Peterson et al., 2021; White & Padtoc, 2021). Viewing stories as multimodal co-constructions of meaning gives credence to the oral, auditory, visual, tactile, gestural, written, and spatial ways that children and teachers make efforts to create stories together in ECE settings.

Sociocultural theoretical perspectives

Sociocultural perspectives allow us to see how story interactions are mediated through material and/or symbolic objects that carry cultural and historic meaning, shaping children’s understanding of their communities and the world (Bruner, 1986). Children’s stories are a heterogeneous aspect of literacy, encompassing genres that include books, oral stories, and conversations about personal experiences (Reese, 2013). Many “small stories” take place during the seemingly ordinary flow of daily interactions, conversations, and routines ( & Georgakopoulou, 2008), although they might be easily overlooked because they are so embedded within those moments. Children learn to participate in stories with others using cultural tools and resources such as language, gestures, and books valued by their communities. In doing so, children develop social and cultural knowledge about how to participate in stories, learning from adults and peers within everyday interactions (Rogoff, 1990).

Co-constructing meaning

Intersubjectivity during story interactions has been the focus of several recent studies in ECE settings. For example, in Norway, Olaussen (2019) explored ways in which toddlers aged 1–3 years engaged in shared orchestrations of meaning in embodied and relational ways during stories enacted through play, while teachers extended toddlers’ story competencies through sensitive noticing and responsiveness. In another study, older children aged 3–5 years in England co-constructed meaning using combinations of eye gaze, body posture, and speech as they enacted and told stories (Cremin et al., 2018). These studies illustrate the power of multimodal perspectives in illuminating the competencies of children of different ages, cultures, and ECE contexts as they co-construct meaning with others in everyday interactions. In this article, we extend this earlier work by using multimodal analysis to explore how 1-year-old and 5-year-old children, in two different countries, co-construct stories with their teachers during shared-book interactions and oral storytelling in Aotearoa New Zealand and northern Canada. With overlapping research focuses situated in our home countries, we reflect on common themes across both ECE settings.

Methods

Video recordings selected for our cross-case analysis come from the pre-existing data sets generated within the two ECE contexts. In each context, a case was identified to explore how children and teachers co-construct stories in multimodal ways. Table 1 describes the ECE context and purpose for the study surrounding each case, with details of location, participating children and teachers, languages spoken, data generation, and consent processes involved.

Two early learning contexts

1. ECE centre in New Zealand

The New Zealand story derives from a 30-second video segment of interaction between teacher Amy and two toddlers JT and Max (all names are pseudonyms) in their ECE centre. Amy has worked in the infant–toddler room of the centre for over 3 years. JT (aged 21 months) is of Indian descent and speaks Tamil and English with his family. Max (aged 16 months) is Filipino and speaks Tagalog and English at home. Both JT and Max’s parents immigrated to Aotearoa New Zealand as adults before JT and Max were born. The video excerpt analysed is a segment of interaction in which Amy, JT, and Max share a book of songs together. The book was a custom-made resource compiled by teachers, comprising a flip-file book of pictures representing toddlers’ favourite songs.

2. Kindergarten in Ontario

Jenna, one of five kindergarten teachers participating in the development of the Language and Nonverbal Communication Assessment (Peterson et al., 2021), has taught for 10 years. Recordings from her classroom were used because she interacted with children to a greater extent than did other teachers in this branch of the NOW Play research. We analysed recordings of four boys’ and one girl’s storytelling, along with Jenna’s verbal interactions with the culturally diverse group of children whose families spoke English at home, as they told a story about a time when they had fun with family or friends. For the most part, children’s stories reflected experiences in their northern, rural environment with many lakes, many square kilometres of dense bush, and small community roads with little traffic. One by one, children sat on a chair facing Jenna. Jenna’s voice is heard in video recordings, but her non-verbal communication modes could not be viewed and analysed apart from voice intonation. This is a limitation of our cross-case analysis, but, because this analysis took place after the original research, it was only possible to gather data about Jenna’s voice intonation.

Multimodal transcription and analysis of videos

Multimodal analysis of selected video extracts allowed for patterns of communication in teacher–child stories to be explored in both studies. Video data were reviewed several times, with and without sound, alongside video logs as we looked for patterns in relation to our research questions (Bezemer & Jewitt, 2010). Examples in this article are drawn from five identified video excerpts that illustrated children’s social and cultural knowledge of stories and/or the multimodal contributions of children and teachers to the co-creation of stories. Selected excerpts ranged between 30 seconds and 3 minutes in length.

We used the Adobe Premier Pro software package to pause and record moments of interaction in the videos while teasing out the layers of spoken, audio, and visual features. Selected snippets of footage were represented as multimodal transcripts. In this article, we illustrate two ways of representing multimodal data: 1) in the transcript of New Zealand data, we foreground visual and written information; 2) in the transcript of Canadian data, we foreground written information with a focus on gestures and verbal language.

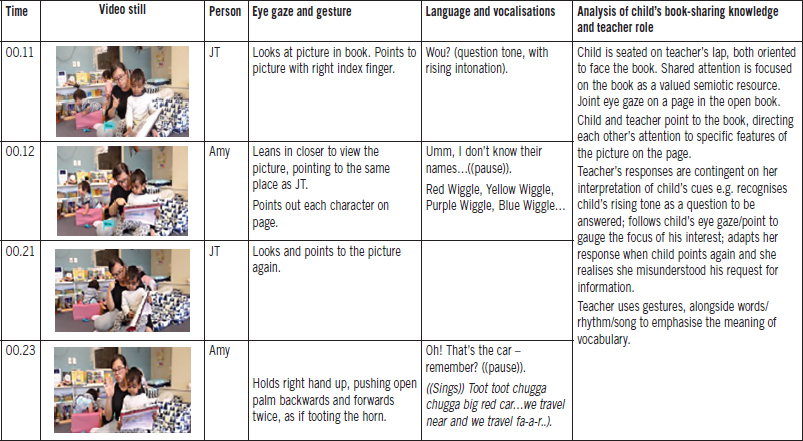

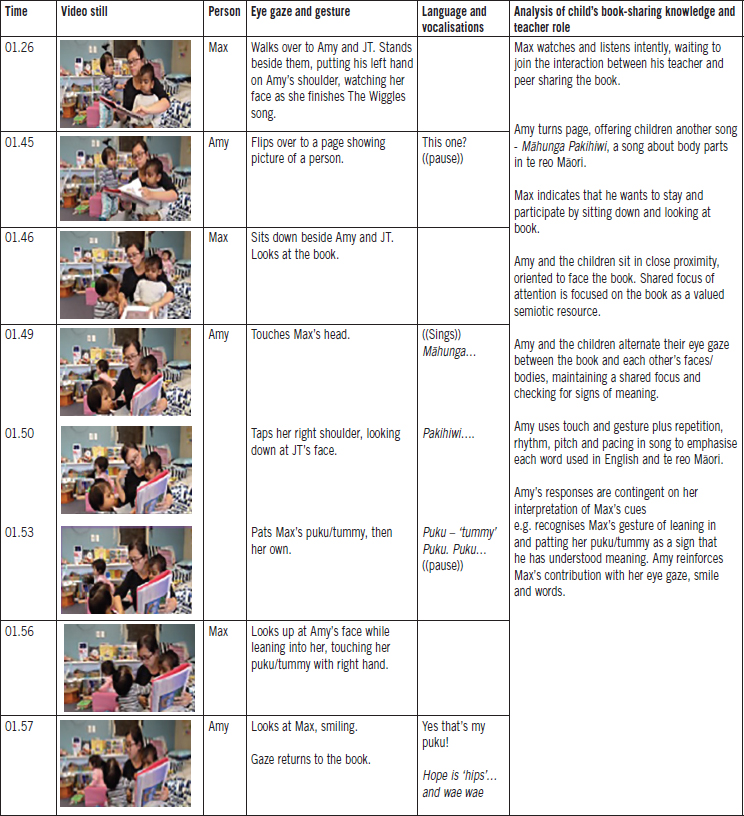

Table 2 shows an example of the multimodal transcription format from the New Zealand study that illustrates how the teacher and children communicate together, moment by moment in this story episode, with modes of eye gaze, gesture, language, and vocalisations shown horizontally, and time shown vertically in the tabular format. Corresponding analysis of social and cultural book-sharing knowledge and teacher role is shown in the right-hand column.

Despite the described difference in our two studies, the iterative process of documenting and reviewing moments of interaction allowed for shared themes relating to our two research questions to become evident. As co-researchers, our ongoing process of sharing video data and discussing interpretations also strengthened the rigour of analysis relating to story co-constructions within and across the studies.

In the following section, we discuss children’s demonstrations of social and cultural knowledge using a range of modes, as well as the roles played by teachers in co-constructing stories.

Teacher–child Interactions in a New Zealand ECE centre

The interaction between teacher Amy and the two toddlers took place one morning in the ECE centre after the toddlers and teachers had shared morning tea. Amy sat on the floor while the toddlers moved freely around her, exploring the infant–toddler room. Video recording began when JT sat on Amy’s knee, bringing the songbook over as a request for Amy to share it with him. Songs, rhymes, and picture books had been identified in parent and teacher interviews as forms of story enjoyed by adults and children together. JT’s actions were, therefore, a cue for the researcher to start recording this interaction as an example of a story in the group setting.

In the selected excerpt in Table 3, JT is sitting on Amy’s lap, looking at a picture representing a song by one of his favourite children’s groups, The Wiggles, as Max approaches the interaction.

This transcript demonstrates the reciprocal and contingent ways that Amy and the toddlers made meaning together while using multiple modes to engage in songs from the book, with examples of children’s cultural knowledge and teachers’ roles.

Children’s social and cultural book-sharing knowledge and communicative modes

While Max and JT did not use any spoken language in this story interaction, they were still actively engaged in the interaction through looking, listening, and embodied actions. Sociocultural understanding of book sharing was demonstrated in the way that children positioned themselves during the story event. JT sat on Amy’s lap facing outwards towards the book. Max joined the interaction by first watching, while letting Amy know he was there by putting his hand on her shoulder. When the page was turned and a new song presented, Max indicated his decision to stay by sitting down and making direct eye contact with Amy as he willingly joined in some of the actions. Amy and the children alternated their gaze between the book and one another’s faces, maintaining a shared focus of attention as they observed and followed one another’s signs of meaning.

Teacher roles in story collaboration

Amy ensured both toddlers were included in the story by shifting her eye gaze between the book and the children, checking in with their facial expressions and body actions. Their close physical proximity enabled Amy to hold JT while also touching heads, shoulders, and tummies as she named each part. Amy used touch and gesture to relate each word to their bodies in a way that linked the Māori and English vocabulary to something tangible and familiar in the “here and now”. Amy modelled the body part concepts in both Māori and English using a slow pace and repetition of words (e.g.,“puku”). Her use of gesture was timed to match each spoken word, reinforcing the meaning visually, kinaesthetically, and verbally. Amy’s use of rhythm and pitch in presenting each word also maintained the toddlers’ attention, along with regular pauses that afforded a more relaxed pace, allowing everyone time to notice, recognise, and respond to one another. Amy followed Max’s cues, acknowledging his gesture of leaning in and patting her tummy as a sign that he understood the meaning of “puku/tummy”. Amy reinforced his response by looking and smiling at him, saying “Yes, that’s my puku!”

Teacher–child interactions in a Canadian kindergarten

Jenna and children’s co-construction of stories started with an invitation to the children: “Tell me a story about a time when you had fun with your family or friends.” The five children used contact, body movement, and, in two instances, gestures, to tell their stories. They demonstrated cultural knowledge about stories and about interacting with a teacher audience. These two themes are developed with illustrative examples in the following.

Demonstrations of story knowledge: The children sometimes started their stories by describing where their family had gone. Carter explained: “I went to Pukaskwa Park and went hiking with Hugo and Hudson and my aunt.” Other times the story began with a description of the setting. Grayson said: “So it was yesterday and me and, like, Kyle, and we were making a tarantula.” Children’s stories also started with an explanation of the overall activity carried out with family members (e.g., Mateo said: “We had a movie night.”)

After establishing the setting, characters, and theme, Lydia and Grayson, the two children who continued their stories without teacher prompting, detailed actions within the setting or elaborated on the theme. Actions were often connected using the word, and. Lydia, for example, continued her story after introducing the setting by saying: “And we went swimming and to a store for clothes.” The other three children provided additional information with teacher prompting, as discussed in the following section.

Children interacting with a teacher audience to tell stories: All five children showed nervousness throughout the video clips by casting their eyes down to the floor, up to the ceiling, and around the room when not telling the story or listening to Jenna. However, when they narrated their story and when Jenna made encouraging sounds, commented, or asked a question, the children looked at Jenna. The excerpt from the transcript of Grayson’s storytelling explaining how he and Kyle made a tarantula in Table 4, shows how his gestures provided information that was not communicated through language. The researcher did not have permission to make the faces of the children public, so no images are provided in this excerpt.

Teacher roles in co-constructed storytelling

Jenna’s talk reflected her genuine interest in the children’s stories and her willingness to try different approaches encouraging children to tell their stories as fully as possible. She prompted children to go beyond their stories’ initial phrases and sentences by making encouraging sounds. For example, after Hayden explained that he had gone fishing with his parents, Jenna vocalised: “Uh huh.” Hayden then added that his brother had also gone fishing. Jenna also helped children move their story along by repeating information that children had previously provided.

Jenna asked each of the five children open-ended questions, often related to the actions in the stories and close-ended questions about the setting, characters, and actions. For example, after Lydia described her family trip to Punta Cana as being filled with swimming and shopping activities, Jenna asked: “What else did you do?” This prompt elicited Lydia’s further description of something she had done in Punta Cana: “I got to ride on dolphins.”

After Matao said he had watched a sad movie with his family, Jenna asked: “What was so sad?” Matao explained: “When he ran away from his dad”, and Jenna responded: “Oh no!” Jenna’s responses took the form of authentic exclamations that are often part of everyday conversation.

Discussion and implications

In this section, we discuss insights about young children’s use of sociocultural knowledge and teachers’ roles during story co-construction within and across the two contexts.

Children’s sociocultural knowledge and story-making

Children in both studies demonstrated that they were competent in orchestrating multiple modes to shape themes and events of their stories (Olaussen, 2019). Differences across contexts were apparent, however, with the 1-year-old children primarily using gesture, facial expression, gaze, and movement with some language to create their stories, whereas the 5-year-old children used language to the greatest extent with some use of gesture and eye gaze. These aspects of communication were highlighted in the multimodal transcripts of story interactions where different combinations of modes were foregrounded across the two settings.

The older children verbally identified various narrative elements such as characters, setting, and action in their personal stories. Younger children identified characters and actions through their gesture, eye gaze, and embodied actions, as highlighted in other studies of early story in ECE settings (e.g., Cremin et al., 2018; Olaussen, 2019). Across both contexts, children showed awareness of social and cultural expectations for engaging in story interactions with teachers. One-year-old Max and JT, for example, drew on their knowledge about participating via looking and listening, as well as the value of books in keeping adults’ attention. Their gaze on the book and their gestures to identify characters’ features led to Amy’s invitation to sit beside her and to her singing, talking, smiling, and gazing. The five-year-old children’s gaze was on Jenna whenever she said something to them and whenever they used language to narrate their personal story. It appears that they were applying sociocultural knowledge about holding the attention of an audience and showing teachers respect through their gaze.

Teacher roles in co-constructed story-making

As the children created stories, teachers served roles as both mediators of semiotic resources and as interested listeners. Amy’s and Jenna’s questions, verbal and non-verbal encouragement, gestures, and gaze were centred on themes, characters, and actions of the stories that were being collaboratively created, with children taking the lead. Both teachers exhibited the expectation that the children were symbolic beings and communicative partners capable of composing stories. Teachers’ questions and prompts in both contexts were respectful of the knowledge and experiences that children brought to the story-making settings and responsive to the information, ideas, and experiences that children were communicating (Hedges & Cullen, 2012).

Silence was part of the collaborative story-making process. Amy and Jenna allowed time for children to draw on their funds of knowledge and modes of communication that they were able to use to create stories. Through waiting for children to respond, the teachers created spaces for children to take turns in the interaction. When the two teachers observed that the children needed input to further their story-making, they repeated what children had previously said, provided encouragement verbally and non-verbally, gestured, and asked questions. Both teachers tried various alternatives to support children’s storytelling.

Amy also supported children’s bilingualism and sociocultural knowledge by using words in te reo Māori and English, reinforced by use of touch, gesture, and song. In New Zealand, use of te reo Māori by teachers in ECE settings reflects their commitment to Te Whāriki, underpinned by bicultural principles of the Treaty of Waitangi where te reo Māori is prioritised (New Zealand Ministry of Education, 2017). In this story interaction, Amy’s concurrent use of te reo Māori and English plus touch, gesture, rhythm, and repetition all served to extend bicultural understandings in a multimodal, playful way that was aptly suited to match the interests and understanding of the 1-year-old children alongside her (Kress, 2013).

Implications

The teacher–child stories shared in this article highlight the importance of considering everyday informal stories constructed between children, adults, and peers as meaningful contexts for extending children’s learning. Adult–child interactions relating to small stories about seemingly ordinary events ( & Georgakopoulou, 2008) have received less attention than print-based story texts in scholarly literature on children’s early learning. We argue that it is important not to overlook the learning potential of children’s personal stories about people, places, and things that feature prominently in their daily lives, even though these stories may not be as structured or complete as more formal story genres.

As well as recognising everyday stories as authentic story contexts, a sociocultural, multimodal lens provides a way for early childhood educators to examine children’s social and cultural knowledge, while also considering the roles teachers play in supporting children to create meaning. Our multimodal analyses demonstrate clear evidence for children’s competencies in co-constructing stories with teachers in embodied and verbal ways, while illuminating some differences that might manifest depending on the ages of children, the sociocultural setting, and the type of story involved.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to participating children, early childhood educators, and teachers for their willingness to share their collaborative storytelling with us. We acknowledge and thank the Social Sciences and Humanities Council of Canada for funding the Canadian branch of this research through a Partnership Grant. We also gratefully acknowledge the Marie Clay Research Centre and Royal Society New Zealand Catalyst Seeding network for fostering our connection and supporting our collaboration.

References

Bamberg, M., & Georgakopoulou, A. (2008). Small stories as a new perspective in narrative and identity analysis. Text & Talk, 28(3), 377–396.

Bezemer, J., & Jewitt, C. (2010). Multimodal analysis: Key issues. In L. Litosseliti (Ed.), Research methods in linguistics (pp. 180–197). Continuum.

Bruner, J. S. (1986). Actual minds, possible worlds. Harvard University Press.

Cremin, T., Flewitt, R., Mardell, B., & Swann, J. (Eds.). (2017). Storytelling in early childhood: Enriching language, literacy and classroom culture. Routledge.

Cremin, T., Flewitt, R., Swann, J., Faulkner, D., & Kucirkova, N. (2018). Storytelling and story-acting: Co-construction in action. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 16(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X17750205

Hedges, H., & Cullen, J. (2012). Participatory learning theories: A framework for early childhood pedagogy. Early Child Development and Care, 182(7), 921–940. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2011.597504

Kalantzis, M., Cope, B., Chan, E., & Dalley-Trim, L. (2016). Literacies (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Kress, G. (2013). Perspectives on making meaning: The differential principles and means of adults and children. In J. Larson & J. Marsh (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of early childhood literacy (2nd ed., pp. 329–344). SAGE Publications.

New Zealand Ministry of Education. (2017). Te whāriki: He whāriki mātauranga mō ngā mokopuna o Aotearoa. Early childhood curriculum. Author.

Olaussen, I. O. (2022). A playful orchestration in narrative expressions by toddlers—A contribution to the understanding of early literacy as event. Early Years: An International Journal of Research and Development, 42(2), 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2019.1600138

Ontario Ministry of Education. (2016). The kindergarten program. Author.

Peterson, S. S., Eisazadeh, N., & Liendo, A. (2021). Assessing young children’s language and nonverbal communication in oral personal narratives. Michigan Reading Journal, 53(2),15–25.

Reese, E. (2013). Tell me a story: Sharing stories to enrich your child’s world. Oxford University Press.

Rogoff, B. (1990). Apprenticeship in thinking: Cognitive development in social context. Oxford University Press.

Schick, A., & Melzi, G. (2010). The development of children’s oral narratives across contexts. Early Education and Development, 21(3), 293–317.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10409281003680578

Wells, G. (1986). The meaning makers: Children learning language and using language to learn. Hodder and Stoughton.

White, A. (2022). Exploring multimodal story interactions between toddlers, families, and teachers in a culturally and linguistically diverse community. Doctoral thesis, University of Auckland.

White, A., & Padtoc, I. (2021). Supporting toddlers as competent story navigators across home and early childhood contexts. Early Childhood Folio, 25(2), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.18296/ecf.0095

Table 1. Summary of methods

|

Aotearoa New Zealand

(White, 2022)

|

Canada

(Peterson et al., 2021)

|

|

Purpose of the larger study

|

To investigate how 1-year-old toddlers experienced story interactions in and across their homes and ECE settings

|

To develop an informal assessment tool for kindergarten teachers to gather information about children’s narrative knowledge, vocabulary and sentence structures, language fluency, and use of non-verbal communication modes to tell a personal story

|

|

Location

|

Urban Wellington

|

Rural Ontario

|

|

Participants

|

Eight 1-year-olds from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds

|

Forty-four children aged 4–5 years old from culturally diverse backgrounds from five kindergarten teachers’ classrooms

|

|

Languages spoken

|

Home languages included te reo Måori, Samoan, Tamil, Farsi, German, English, and Tagalog

English was the primary language spoken in ECE centres, with some reo Måori

|

English

|

|

Data collection methods

|

Video observations and interviews with parents and teachers

|

Teacher-directed video recordings of the children

|

|

Consent process

|

Parent and teacher written consent. Video recording gradually introduced while closely monitoring the ongoing assent of all participants throughout the study

|

Parental written consent and children’s verbal assent

|

TABLE 2. JT AND AMY ENGAGE IN THE “BIG RED CAR” SONG BY THE WIGGLES

TABLE 3. MAX, JT, AND AMY ENGAGE IN MÅHUNGA PAKIHIWI, A SONG IN TE REO MÅORI ABOUT PARTS OF THE BODY

Table 4. Grayson’s gestures and language to describe his

and Kyle’s tarantula making

|

Gestures

|

Language

|

|

Grayson made a rectangular shape with his hands to create the bag in which he put the tarantula. He looked at his hands and then moved his hands back and forth to show dimensions of the bag.

|

So we had um, a thing with a bag.

|

|

Grayson brought his hands together so all fingers and both palms were touching and motioned downwards.

|

and we . . . this yellow thing which we put the tarantula in. Then we put it in um, the bag . . .

|

|

Grayson separated his right hand with all four fingers and thumb together away from his left hand and then pointed his index finger on his flattened left palm as if pressing a button. His eyes were cast downward, looking at his pointing finger.

|

and then we had to press the button until it stopped.

|

Amanda White’s research interest centres on early childhood communication and literacy. Amanda recently completed her doctoral research at the University of Auckland, using video methods to explore children’s multimodal story interactions. She worked previously as a speech-language therapist and is now a researcher / kairangahau at the New Zealand Council for Educational Research (NZCER). Email: amanda.white@nzcer.org.nz

A former elementary teacher in rural western Canada, Shelley Stagg Peterson is a professor in literacy education in the Department of Curriculum, Teaching and Learning of the University of Toronto, Canada. Email: shelleystagg.peterson@utoronto.ca

Emma Quigan (Kai Tahu) is the work-integrated learning coordinator at Massey University for the Bachelor of Speech and Language Therapy programme. She is a registered speech-language therapist (SLT) and the Co-President of the New Zealand Speech Therapy Association. Emma completed her master’s degree in 2018, investigating the power of SLTs divulging power and supporting parents to coach other parents on early language skills. Email: e.quigan@massey.ac.nz