Assessing and building wellbeing

Sally Boyd

A sense of belonging and wellbeing at school influences educational and health outcomes. Here we widen the traditional focus of Assessment News to focus on the use of student wellbeing data in schools. We discuss the Wellbeing@School (W@S) toolkit that is freely available to support schools to self-review as they examine and monitor student wellbeing (including measures of bullying) from the perspectives of teachers and students. Key findings from national-level W@S data, plus other New Zealand and international studies, suggest areas that might be important for schools to focus on. We encourage schools to plan for a continuous improvement process that aims to build a stronger school-wide climate and infrastructure around students.

Broadening our assessment focus can help us foster wellbeing

Traditionally, much of the formal assessment focus in schools is about tracking and improving learning outcomes such as students’ reading comprehension or their understanding of mathematics concepts. There are a number of compelling reasons to think about widening our focus to assess, track, and improve other areas. Wellbeing is one such area. Below are some examples of questions that schools could ask about student wellbeing.

•What do we know about students’ wellbeing at this school?

•Do we have a mix of actions and strategies in place at this school that aim to foster wellbeing? Do these actions include some that proactively promote belonging and wellbeing; and others that effectively address actions, such as bullying behaviour, that are detrimental to wellbeing?

•Are these actions and strategies based on evidence about what works, and are they monitored and improved over time?

•What processes do we have to involve students, staff, and parents and whānau in decision-making about wellbeing at this school?

•What are the different ways we harness students’ views and capabilities to support this school to foster wellbeing?

This article explains why these questions matter, introduces the Wellbeing@School (W@S)1 toolkit that schools can use when exploring these sorts of questions, and considers what a summary of national W@S data can tell us about the needs of New Zealand students and the practices that make a difference in schools.

The Wellbeing@School toolkit

The Wellbeing@School (W@S) toolkit was developed by NZCER for the Ministry of Education. It is provided free of charge to New Zealand schools. This toolkit can assist schools to self-review and plan ways to foster wellbeing. W@S primarily focuses on social wellbeing. However, it also includes a focus on two of the other dimensions of hauora in te whare tapa whā:2 mental and emotional wellbeing, and spiritual wellbeing.

W@S was developed from research about strengthening school climates and addressing bullying behaviour (Boyd, 2012). Student and teacher survey tools explore the aspects of school climate that contribute to social wellbeing. The student survey also includes an aggressive behaviour scale which includes questions about the extent to which students experience aggressive and bullying behaviour at school. Schools can use W@S data to identify needs and track change over time.

A sense of belonging and wellbeing at school influences educational outcomes

In New Zealand, and internationally, we are becoming more aware of the need to foster wellbeing in school settings. We know that students are unlikely to learn if they don’t feel safe or feel they don’t belong. We also know that effective social and emotional learning is a protective factor that fosters wellbeing and has many other benefits. One international meta-analysis showed benefits in six main areas: enhanced academic performance, social and emotional skills, attitudes toward self and others, and social behaviours; and decreased emotional distress and lower levels of conduct problems (this category including bullying, disruptive class behaviour, aggression, and school suspensions) (Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor, & Schellinger, 2011).

The importance of fostering students’ wellbeing is clearly stated in the vision of The New Zealand Curriculum (Ministry of Education, 2007). The National Administration Guidelines (NAG 5) (Ministry of Education, n.d.) state that New Zealand schools have a responsibility to provide a safe emotional and physical environment for students. The update of the Education Act includes objectives related to wellbeing such as schools promoting the development of:

•resilience, determination, confidence, and creative and critical thinking

•good social skills and the ability to form good relationships (Ministry of Education, 2018).

Increasingly, the New Zealand Government is also recognising the need to focus on young people’s wellbeing. A proposed outcomes framework (Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, n.d.) that is part of the Government’s children and youth wellbeing strategy aims to monitor and improve wellbeing outcomes in six areas, including that all children and young people:

•are loved, nurtured, and safe (e.g., communities, including at school and online are safe and supportive, with children and young people protected from victimisation)

•have what they need

•belong, contribute, and are valued (e.g., are actively included in schools, community, and society)

•are healthy and happy (e.g., children and young people experience mental wellbeing)

•are learning and developing.

The W@S self-review toolkit can support schools or Communities of Learning / Kāhui Ako to self-review and strengthen approaches related to these outcomes.

New Zealand has a high rate of bullying behaviour which is detrimental to wellbeing

New Zealand data suggests we have some work to do. International studies show that we have high rates of bullying behaviour in our schools compared to other countries (Martin, Mullis, & Foy, 2008; Ministry of Education, 2017; Mullis, Martin, & Foy, 2008; Mullis, Martin, Foy, & Hooper, 2016).

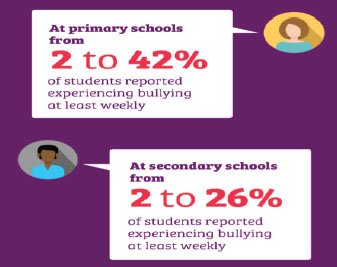

An analysis of national W@S student and teacher survey data (Lawes & Boyd, 2017, 2018) also found high rates of bullying behaviour reported by students, and wide variation between schools in the average rate of this behaviour.

Bullying behaviour has many negative impacts on students. Being involved in bullying as either a target or perpetrator is associated with poorer short and longer-term health and education outcomes for young people (Wylie, Hipkins, & Hodgen, 2008). Being a target of bullying is detrimental to young people’s mental health and contributes to suicide behaviours (Fortune et al., 2010), and New Zealand’ high rate of youth suicide is an ongoing concern for us all (Gluckman, 2017; OECD, 2009).

In the 1990s, a key longitudinal study showed us that a sense of connectedness to school is a protective factor related to positive longer-term education and health outcomes for young people (Resnick et al., 1997). To give all students the best start at education, we need to create a space where they feel they belong. The national W@S analysis found substantial variation in the extent to which students reported they felt they belonged at school, and in the extent to which schools engaged in actions that fostered wellbeing.

Changing the system around students can assist in fostering wellbeing

Assessment of learning outcomes such as literacy primarily look at the situation of individual students or classes. To assess wellbeing we can also use tools that identify individual students who may need more support.3 However, to best support student wellbeing we need to broaden our concept of assessment from a singular focus on individual traits to one that also recognises the infrastructure and system around students. We know that students’ wellbeing is influenced by the different layers of school life including the social climate of a school, how relationships and belonging is fostered, how extra support is provided, as well as what happens in the classroom. W@S is designed to explore these and other aspects of the system around students.

Schools can use local evidence to design a Whole School Approach to promote wellbeing

Evidence suggests Whole School Approaches are an effective way of building a health and wellbeing focus in schools (Langford et al., 2015, 2015; Smith, 2011; Ttofi & Farrington, 2011). A multifaceted action plan to foster wellbeing is an aspect of a Whole School Approach. Whole School Approaches commonly include a range of actions that relate to the different layers of school life, rather than single solutions, such as a curriculum approach.

One question that is often asked is‚ “What are the most important actions to include in our plan?” National W@S data provides us with some ideas. In the schools where staff reported more school-wide actions were in place, students reported lower rates of bullying behaviour (Lawes & Boyd, 2017, 2018). These school-wide actions included five subgroups of practice:

•collaborative leadership

•creating a wellbeing culture

•effective policies and practices

•support for students

•prioritising professional learning and development.

One example of an action that can make a difference is consistent and fair behaviour management. This practice falls under the heading of Effective Policies and Practices. Only two-thirds of teachers in the W@S analysis agreed that “Behaviour management policies or procedures are applied consistently and fairly to all students”, suggesting this is an area where changes in practice could make a difference. In the recent Education Matters to Me student consultation, building a stronger sense of fairness was one of things students would like to change about their school (Office of the Children’s Commissioner & NZ School Trustees Association, 2018a, 2018b). A review of 133 studies on school relationships, and their impact on student mental health and academic learning, found perceived levels of teacher support and fairness were key teacher behaviours which fostered good relationships than in turn contributed to positive mental wellbeing for young people (McLaughlin & Clarke, 2010).

Effective support for students can also make a difference. The Youth 2000 surveys of secondary school students tells us that schools with well-structured, on-site health services have better wellbeing outcomes for students including lower levels of reported depression and suicide risk (Denny et al., 2014). Denny et al. also found that health services provision varied substantially between secondary schools. W@S explores different forms of support for students. As one example, our national analysis showed that three-quarters of teachers agreed that their school provided extra support for students who were the target of bullying or harassment (such as counselling).

Social and emotional learning is a core part of a Whole School Approach

What happens in the classroom is a core part of a Whole School Approach. W@S data showed that, in schools where teachers planned a focus on the social and behavioural skills they would like to develop, and used active teaching strategies, students reported higher levels of social wellbeing (Lawes & Boyd, 2017, 2018). Examples of these active strategies included: teaching students to manage their feelings in non-confrontational ways; using classroom discussion time for students to share and resolve any concerns they have; and using role plays or drama activities to support students to develop and practise effective strategies for relating to others.

The national W@S data also showed variations between schools in the extent to students felt they had strategies to manage their wellbeing, which suggests that students could benefit from an increased focus on planned social and emotional learning. For example, over one-third of students disagreed that they can say how they are feeling when they need to, and around one-third disagreed they had help-seeking skills such as asking another student or teacher for help if they were having a problem with another student (Lawes & Boyd, 2018).

It’s not just about data, it’s also about working collaboratively

Collecting data is important, but so is the process that is used to collect and unpack it and decide on ways forward. Collecting data can help to identify needs and show if actions are making a difference. However trying to shift the climate of a school to better promote wellbeing and deter actions such as bullying behaviour is not something that happens overnight. We all need to be on the waka for the long haul.

As noted above, collaborative leadership is an example of a school-wide action that makes a difference. The W@S support materials and Whole School Approaches promote this style of leadership. Data is seen as one starting point for collaborative sense-making conversations with all key stakeholders—including students. Students are our core stakeholders—the education system is for them. We want our students to leave school with a sense of individual and collective agency and the ability to effect change in their own environments (Hipkins, Bolstad, Boyd, & McDowall, 2014). The active involvement of young people in creating change is particularly important in trying to address issues such as bullying behaviour because of its covert “under the radar” nature. Research shows much of this behaviour is not reported to adults, but also that the actions of student bystanders can either maintain or disrupt negative peer norms (Salmivalli, 1999; Winslade et al., 2015). Therefore partnering with students as co-developers of a school action plan is a vital facet of any approach that aims to address behaviours that are detrimental to their wellbeing.

Final thoughts

This article aims to prompt reflection about the data collected in schools and the processes that could be used to ensure this data is one stepping-off point to create change. We hope that the evidence and ideas presented can help schools to think about how the system around students can be redesigned to better support their wellbeing. To assist in this process, the W@S toolkit includes resources such as reports that can identify areas to build practice, an action planning template4, and archived data from surveys with your teachers and students that can be used to track change over time.

McLaughlin and Clarke (2010) make the point that there is a complex “spider web” (p. 99) of interconnections between relationships, belonging, engagement, and wellbeing, and argue for greater pedagogical and policy attention to be paid to this spider web. It is important that we are all thinking about how we can be more purposeful about our approaches to this spider web and what it might mean for our assessment practices.

Notes

References

Boyd, S. (2012). Wellbeing@School: Building a safe and caring school climate that deters bullying— Overview paper. Wellington: New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Denny, S., Grant, S., Galbreath, R., Clark, T., Fleming, T., Bullen, P., ... Teevale, T. (2014). Health services in New Zealand secondary schools and the associated health outcomes for students. Auckland: New Zealand: University of Auckland.

Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. (n.d.). Child wellbeing strategy proposed outcomes framework: New Zealand is the best place in the world for children. Retrieved from https://dpmc.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2018-11/appendix-b-proposed-outcomes-framework.pdf

Durlak, J., Weissberg, R., Dymnicki, A., Taylor, R., & Schellinger, K. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432.

Fortune, S., Watson, P., Robinson, E., Fleming, T., Merry, S., & Denny, S. (2010). Youth ’07: The health and wellbeing of secondary school students in New Zealand: Suicide behaviours and mental health in 2001 and 2007. Auckland: The University of Auckland.

Gluckman, P. (2017). Youth suicide in New Zealand: A discussion paper. Wellington: Office of the Prime Minister’s Chief Science Advisor.

Hipkins, R., Bolstad, B., Boyd, S., & McDowall, S. (2014). Key competencies for the future. Wellington: NZCER Press.

Langford, R., Bonell, C., Jones, H., Pouliou, T., Murphy, S., Waters, E., ... Campbell, R. (2015). The World Health Organization’s Health Promoting Schools framework: A Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 15(130).

Lawes, E., & Boyd, S. (2017). Making a difference to student wellbeing. Wellington: NZCER. Retrieved from http://www.nzcer.org.nz/infographic-making-difference-student-wellbeing

Lawes, E., & Boyd, S. (2018). Making a difference to student wellbeing—a data exploration. Wellington: NZCER.

Martin, M., Mullis, I., & Foy, P. (2008). TIMSS 2007 international science report. Chestnut Hill, MA: TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center.

McLaughlin, C., & Clarke, B. (2010). Relational matters: A review of the impact of school experience on mental health in early adolescence. Educational & Child Psychology, 27(1), 91–103.

Ministry of Education. (n.d.). The National Administration Guidelines (NAGs). Retrieved from https://www.education.govt.nz/our-work/legislation/nags/

Ministry of Education. (2007). The New Zealand curriculum. Wellington: Learning Media.

Ministry of Education. (2017). PISA 2015 New Zealand students’ wellbeing report. Wellington: Author.

Ministry of Education. (2018). Establishing enduring objectives for the education system. Retrieved from https://www.education.govt.nz/our-work/legislation/the-education-update-amendment-act-2017/establishing-enduring-objectives-for-the-education-system/

Mullis, I., Martin, M., & Foy, P. (2008). TIMSS 2007 international mathematics report. Chestnut Hill, MA: TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center.

Mullis, I., Martin, M., Foy, P., & Hooper, M. (2016). TIMSS 2015 international results in mathematics. Boston: TIMSS and PIRLS International Study Center.

OECD. (2009). Doing better for children. Paris: Author.

Office of the Children’s Commissioner, & NZ School Trustees Association. (2018a). Education matters to me: Key insights. Wellington: Author.

Office of the Children’s Commissioner, & NZ School Trustees Association. (2018b). He manu kai mātauranga: He tirohanga Māori. Education matters to me: Experiences of tamariki and rangatahi Māori. Wellington: Author.

Resnick, M., Bearman, P., Blum, R., Bauman, K., Harris, K., Jones, J., ... Udry, J. (1997). Protecting adolescents from harm. Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. Journal of the American Medical Association, 278(10), 823–832.

Salmivalli, C. (1999). Participant role approach to school bullying: Implications for intervention. Journal of Adolescence, 22(4), 453–459.

Smith, P. (2011). Why interventions to reduce bullying and violence in schools may (or may not) succeed: Comments on this Special Section. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 35(5), 419–423.

Ttofi, M., & Farrington, D. (2011). Effectiveness of school-based programmes to reduce bullying: A systematic and meta-analytic review. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 7, 27–56.

Winslade, J., Williams, M., Barba, F., Knox, E., Uppal, H., Williams, J., & Hedtke, L. (2015). The effectiveness of “Undercover Anti-Bullying Teams” as reported by participants. Interpersona: An International Journal on Personal Relationships, 9(1), 72–99.

Wylie, C., Hipkins, R., & Hodgen, E. (2008). On the edge of adulthood: Young people’s school and out-of-school experiences at 16. Wellington: Ministry of Education.