Changing the conversation

(Toe fetu’una’i manatunatuga)

Exploring and utilising the attributes that are culturally embedded in Pacific students to improve their learning experiences in the classroom

Talitiga Ian Fasavalu and Kate Thornton

Key points

•Pacific students’ success is imperative to building a stronger New Zealand and scholars have identified factors that positively influence Pacific students’ learning experiences.

•An action-research pilot project was conducted to utilise attributes that are culturally embedded in Pacific students in order to improve their learning experiences.

•Talanoa was used as a method to elicit valuable information and guide the conversations.

•The skills focused on in the mentoring of three Pacific students were asking effective questions and providing support through language integration to better understand complex learning concepts, to drive the conversation and extract valuable information.

•Both the students and their teacher noticed positive change and were encouraged to change the dynamics of the classroom so students can learn from and with one another.

Pacific students’ success has been under discussion by Pacific scholars for decades and, using traditional academic measures, their academic success does not compare well with other ethnic groups. Despite the identification of this problem, specific and practical actions to counter it appear not to be well understood by classroom teachers. This article explains an action-research pilot programme that was put in place to improve Pacific students’ learning experiences with the hope that it would also help improve their academic results. The intervention focused on changing the conversation that happens outside the classroom, and exploring and utilising the attributes that are culturally embedded in Pacific students. Talanoa was used as a method to elicit information and guide the conversation.

Introduction

Pacific peoples is an umbrella term used to refer to people currently living in New Zealand who are from the islands in the Pacific Ocean. The term Pasifika has been commonly used up until recently, however this use has been critiqued by scholars such as Mara (2019) who believe the term Pacific is more culturally appropriate. While Pacific peoples share similar values, languages, traditions, and ancestry, every Pacific island nation has its own distinctiveness (Manu’atu & Kepa, 2002). Airini et al. (2011) state that, by 2021, Pacific people will make up at least 25% of New Zealand’s population. Therefore, the success of Pacific students at secondary and tertiary level is vital and strategically relevant to building a stronger New Zealand. However, Pacific students are often identified as being less successful than most other ethnic groups in traditional academic measures of educational success (New Zealand Qualifications Authority [NZQA], 2018).

The first author of this article, Talitiga Ian Fasavalu, was born and raised in Samoa and migrated to New Zealand in 2001 at the age of 16. He could not read or speak English on arrival; however, he persevered through all the educational challenges he faced and was able to navigate to the dry grounds he stands on today. He has been a secondary school teacher for 9 years. The personal pronoun used in the rest of the article refers to his perspective. The second author, Kate Thornton, was the lecturer in a postgraduate course in coaching and mentoring taken by the first author. Thornton contributed to the writing of the article.

Talitiga Ian Fasavalu’s experience

My frame of reference is born from my own experience through the education journey I took as a Pacific student learning in a system that does not value my beliefs and expectations. My hope is to create a platform where Pacific students like me can be equipped and empowered to understand that they have already obtained the culturally embedded attributes to navigate successfully within the current education system in New Zealand.

At the beginning of every school year since I began teaching, the previous years’ National Certificates of Educational Achievement (NCEA) results have been reflected on. Those of Pacific ethnicity are less successful in terms of academic achievement in my school. This concerns me because, although the need to improve Pacific achievement has been identified, no specific actions are put in place to improve students’ experience. The exceptions are catch-up workshops provided at the end of the year to get these students “over the line”; that is, to achieve at a level which looks like a success for the school in terms of statistics. The majority of study units offered in these workshops are irrelevant to Pacific students’ realities and their life outside of the school environment. The frustration caused by this situation motivated me to create a mentoring initiative to allow Pacific students to exercise the attributes that are culturally embedded in them and to equip them to use these attributes to achieve in the current education system well beyond “the line”. This article explains a pilot programme involving action research and talanoa methodology that was designed as part of my postgraduate study and put in place to improve Pacific students’ learning experiences with the hope that it will also help improve their academic results.

What we know about Pacific achievement

Many Pacific education researchers, such as Schumacher (1998), Anae et al. (2001), Rakena, Airini, and Brown (2016), and Airini et al. (2011), have identified factors contributing to Pacific students’ underachievement in the New Zealand education system. The following section will explain some of these issues and what has been suggested to improve educational success among Pacific students..

The perception of schools and teachers about their Pacific students is a significant factor in their academic success. Teachers may come with preconceived ideas of Pacific students based on prior achievement, and these ideas may hinder the teacher’s ability to implement strategies to improve Pacific students’ results. Scholars such as Jones (1991) and Delpit (2006) show that teachers seem to “teach down” on Pacific students when they do not recognise their strengths. However, having high expectations is imperative to a student making progress, and seeing Pacific students as achievers can and will contribute to their success.

Another issue identified in the literature is the constant pull of Pacific students from familiar environments to less-familiar ones. This often occurs without a real consideration of the impact that change has on a student’s educational experience. Schumacher (1998) states that harm is caused when students transition from familiar settings to unfamiliar ones. Raivoka, cited in Kabini and Chu (2009), has explained how his values and beliefs were discouraged by the school principal as he was told to leave them at the gates before entering the school every morning. This disconnection from familiar environments is likely to significantly contribute to the lack of success of Pacific students. Academically successful Pacific students may have been encouraged to lose their identity and, as Taufe’ulungaki (2009) explains, Pacific educational success in a Western education system comes at great cost to families and communities.

Scholars such as Airini, Anae, and Mila-Schaaf (2010) and Fletcher, Parkhill, Fa’afoi, Taleni, & O’ Regan (2009) highlight establishing relationships between teacher and students as one of the keys to Pacific students’ success in education. Gorinski and Abernathy (2007) suggest that it is fundamental to establish positive and reciprocal relationships between teacher and learner in order for students to develop self-efficacy and subsequent success. Anae et al. (2001) state that Pacific students thrive through the promotion of strong relationships between teacher and students, when teaching is student-centred, and there are high expectations that all students can achieve. Chu et al. (2013) also acknowledged teaching relationships as one of three key components that contribute to Pacific success, along with appreciative pedagogy and institutional commitment to Pacific success.

Utilising Pacific tools

There has been a huge shift in the academic realm in terms of utilising the attributes that are culturally embedded in Pacific people to improve the learning experience of a Pacific learner in predominantly Westernised curricula and education. Indigenous institutions such as Curtin University of Technology in Western Australia (Abdullah & Stringer, 1999) and Māori-medium institutions seek to apply the philosophy of making the learner’s own culture central to their learning. They have been successful in raising indigenous or minoritised students’ academic achievement. Indigenous and Pacific researchers such as Thaman (1993), Gegeo and Gegeo (2000), and Sanga and Chu (2009) have also explored traditional ways of learning in order to develop a learning identity in Pacific contexts. For example, Gegeo and Gegeo’s (2000) study highlighted the use of traditional learning techniques of the village to improve English learning in the Solomon Islands.

Sailing and navigation has been a huge part of the lives of Pacific peoples. According to history, our ancestors mastered the art of adaptation in order to control and direct sails through the unforgiving currents of the seas (Tamayose & De Silva, 2017). Scholars such as Si‘ilata, Samu, and Siteine (2017) and Taleni, Macfarlane, Macfarlane, and Fletcher (2017) have used the notion of duality to make meaning between Western perspectives and traditional ways of thinking. This interweaving of two perspectives is also supported by Taleni et al.’s (2017) work on leadership qualities. They suggest that in order to be an effective leader one must also take into consideration traditional leadership qualities embedded within cultural values such as integrity, love, reciprocity, spirituality, respect, and belonging. Such action will allow one to navigate effectively through educational changes for the betterment of Pacific learning experience and achievement.

“Indigenous institutions such as Curtin University of Technology in Western Australia and Māori-medium institutions seek to apply the philosophy of making the learner’s own culture central to their learning.”

Si‘ilata (2014) developed the Va‘atele Framework as a metaphor for Pacific success. The analogy of the va‘atele (the double hulled deep sea canoe) may be applied to Pacific learners as they navigate their way through the education system “in order that schools and educators might understand how it is possible to both privilege and utilize students’ linguistic and cultural resources within curriculum learning at school” (Si‘ilata, Samu & Siteine, 2017, p. 1). Notions of Pacific success should include Pacific learners’ linguistic and cultural identities, and schools must examine critically whose knowledge is valued at school.

There has also been a push to focus on education-based mentoring by scholars such as Chu (2009), Mara and Masters (2009), and Farruggia et al. (2011). Pacific students view mentoring as a relationship of influence that can counter the lack of positive relationships with teachers within schools (Chu, 2009). Chu also emphasises the need to create a space where Pacific students can relate culturally in order to enhance academic success.

This literature has highlighted reasons why Pacific students are underachieving according to academic notions of success in the New Zealand education system and has identified strategies the current education system needs to consider to see Pacific students succeed academically. These strategies involve strengths-based approaches focusing on what is working already and utilising the skills and attributes that are culturally embedded in Pacific students to equip them to know that they, too, can experience success in an unfamiliar education system. Resources such as Tapasā (Ministry of Education, 2018) provide guidance for teachers on how to improve engagement with Pacific learners and there are also case-study reports with a focus on school leadership practices that support Pacific student achievement and success (Ministry of Education, 2016) which illustrate that many teachers can and do make a difference to Pacific student learning. As a teacher of Pacific students, I take full responsibility for the students I teach, hence my venture to rethink and create a mentoring space utilising the strengths identified from the literature to improve Pacific students’ educational experiences. My study, focused on coaching and mentoring, encouraged me to try a different approach which is explained below

This literature has highlighted reasons why Pacific students are underachieving according to academic notions of success in the New Zealand education system and has identified strategies the current education system needs to consider to see Pacific students succeed academically.

Research approach

This action-research project focused on engaging three Samoan students in meaningful conversations to recognise and utilise their culturally embedded attributes to improve achievement in their chosen subject. The intervention involved student-driven conversations based on the content these students were learning in their chosen topic. The value of changing the conversation was born from my own experiences as a learner. I wanted to re-create this space for these three students so that they were comfortable to share their learning experiences. Building relationships at the start was vital as the students needed to be comfortable to open up.

The project utilised the talanoa methodology. Talanoa is a tool used to gain valuable information for analysis purposes. Vaioleti (2006) defined talanoa as talking about nothing. Halapua (2008) understood the concept as engaging in dialogues with, or telling stories to, each other. Farrelly and Nabobo-Baba (2014) alert us to the emotional connection and the deep empathic understanding necessary in those exchanges. Sanga and Reynolds (2018) introduced “tok stori” which is a Melanesian term similar to the concept of talanoa. Tok stori can be understood as a relational ontology where the act of storying contributes to relational closeness as a shared reality is constructed (Sanga & Reynolds, 2018).

I wanted to utilise aspects of these interpretations of talanoa in a mentoring platform because talanoa is a practice Pacific people are familiar with. I saw an opportunity to explore talanoa in a mentoring platform as the principles of research and mentoring are similar (Chu, 2009). Therefore, as the mentor/coach, I need to identify the skills that best guide the conversation and allow the students to stay engaged in the education-centred process. The two skills I chose for this specific intervention were first, asking effective questions—a concept discussed below—and secondly, providing support through language use and language integration.

Grant and O’Connor (2010) state that asking effective questions is vital and the heart of coaching conversations. Pelan’s (2012) study highlights that a good coach asks the right questions instead of giving the right answers. Asking open-ended questions can allow the students to explore and discover new ways of thinking for themselves (Thomas & Smith, 2009). I wanted to improve my questioning ability to guide the talanoa better. From my own observation of the Samoan culture, a conversation about anything to do with education sounds as such: “Uaumanafai au meaaoga” (Have you done your homework?) or “E iaini au meaaoga e fai?” (Have you got homework to do?). The approach lacks curiosity. There are no open-ended follow-up questions that allow the student to explain or describe a learning story. However, when discussing sports or other matters, the conversations are filled with laughter and good feelings, with both parties connecting, exploring, and enjoying the process. I wanted to explore how this energy could be re-orientated to telling learning stories. Thus, I followed McLaughlin’s (2017) steps of asking curious questions to improve my questioning. For example, she believes asking rather than knowing is at the heart of an intelligent inquiry. Therefore I intentionally positioned myself as a learner as I was curious about what these three students were learning in their class.

The second skill I wanted to improve on was providing support through integration of Samoan and English language. The three students I mentored are all beginners as English speakers. Thus, I decided to explore how I could utilise my Samoan language to teach and translate certain concepts that the students do not understand. However, the amount of support I intended to provide was dependent on the amount of support the students needed (Ruru, Sanga, Walker, & Ralph, 2013). Brockbank and McGill (2006) state that comments such as, “I like the way you …” or using the word “and” rather than “but” are better for students’ learning than evaluation or comparison. Knowing this, I wanted to improve on my responses to their questions by not shutting down their ideas but finding a way to allow them to rethink the situations or come up with a different point of view. Therefore, I needed to be cautious about what I said and how I said it.

Participants

Three students who recently migrated from Samoa participated in this project. Two were 18 and one 19 years old, and all were in their last year of school at a high school in the Wellington region (not the first author’s school). While this is a small sample, the experience of these students may be of interest to those working in education as their experiences are unlikely to be unique. The students were given an information sheet explaining the research and all gave written informed consent. They were given the opportunity to select a subject that they were all enrolled in for the purposes of the mentoring and coaching conversations. We met on Thursdays every week for 5 weeks for between 1–2 hours. As their mentor/coach I focused mainly on changing the conversations outside the classroom, trying to encourage these students to share their learning stories about their progress in class each week. The assumption is that, in talanoa, when one shares a story, others can either relate, challenge, or expand on the points mentioned. In doing so, those involved extend on their own prior knowledge and gain confidence in their ability to learn within class.

I wanted to improve my questioning ability to guide the talanoa better. From my own observation of the Samoan culture, a conversation about anything to do with education sounds as such: “Uaumanafai au meaaoga” (Have you done your homework?) or “E iaini au meaaoga e fai?” (Have you got homework to do?). The approach lacks curiosity. There are no open-ended follow-up questions that allow the student to explain or describe a learning story.

Findings

The intervention was divided into five sessions. The first session was short as I was only aiming to lay out the purpose of the intervention. Therefore, the conversation started with my explanation of what was expected from them during the intervention. The second session aimed to identify what these students were struggling to learn in their chosen subject as well as how much support they needed.

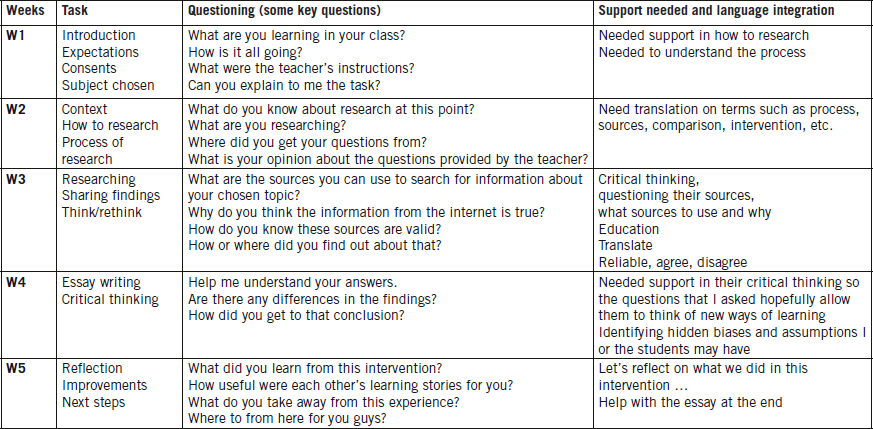

As the mentor, I needed evidence of my current questioning practice as well as how much support I give. Therefore, I recorded this session to get a snapshot of the progress of the session as well as the questions that came easily for me to ask. Each student had an opportunity to answer, and from there I was able to guide the conversation. I asked questions like: “What are you guys learning about in this subject?” which positioned me as a learner in this situation as I was curious to know what they were learning in their chosen subject. Once the needs were identified, in the second session I organised the rest of the sessions into specific focuses. Table 1 explains how the sessions were broken down.

The students identified a few issues that they were dealing with in class. The conversation indicated the need for the students to learn how to research their chosen topic, in this case the Mau Movement, which can be historically linked to Samoa gaining independence, a task that they were expected to do to gain the available NCEA credits. Students shared how their teacher overloaded them with internet resources and with instructions to copy what they found from the internet and paste it into their workbook. The workbook would later be used as a resource for writing their essays, the final piece of the task.

The students also reflected on their relationship with the teacher and indicated that it only existed when they asked for help. Students’ comments revealed the lack of a strong relationship between them and their teacher and it seemed clear that they felt that the teacher had low expectations of them.

I decided to support the students to learn how to research and formulated some key questions to drive the conversations. Instead of teaching them how to research, I asked questions like “What do you know about research?” or “How can we research your topic?” These questions cued the conversation to use the knowledge that they had already attained and, while one student shared what she knew, the others started to identify the links, therefore creating new knowledge.

Because of the nature of the intervention, some questions I asked had to be thought of on the spot as I did not know the content of the conversation until we were operating in that moment. I knew I must ask open-ended and curious questions. Therefore, I had to be actively listening throughout the session, anticipating the best time and questions to ask. I wanted to make sure that the questions I asked would challenge the students and also encourage them to reflect on their learning, thus enhancing their motivation and helping their learning. I stayed open minded about what questions to ask and when to ask them.

As the students increased their confidence, my level of support decreased. This transition was clear by comparing the first and the last sessions. At the start, students seemed a bit shy and just answered questions. However, at the end, students were confident enough to question one another’s point of view, debate issues, and form new learning.

Discussion

This intervention was student-driven so its success was measured by how the students felt at the end of the process as well as their academic success. At the start of the intervention, these three students reflected on what I considered accounts of poor teaching practice. This teacher’s actions seemed to confirm the deficit theory identified in the literature more than two decades ago. For instance, Jones (1991) identified how teachers teach down to their students when they do not recognise their strengths, hindering students’ learning experiences. Therefore, students are not able to reach their full potential and their confidence declines as a result. Although my conclusions in this project are based on three students’ feedback and reflection only and it would have been interesting to hear the teacher’s perspective so as to minimise the assumptions made during the intervention, the likelihood that deficit theorising persists is disturbing.

TABLE 1. TIME FRAME

I was always aware that the participants were beginners as English speakers so I was constantly checking to see if they understood terms I used and terms they had come across in school. When the students were stuck during the conversation, I was able to ask questions or reflect on the points they made. This allowed the students to extend the points, debate issues, and use questions so they could understand the subject better. Chu (2009) refers to this process as new knowledge created from the relationships formed through conversations between people, rather than individual group members.

I also noticed a change in the language I used when I was asking questions. In the beginning sessions, I found through the recordings that I was demanding a lot in terms of asking the questions to guide them towards where I wanted them to go. For example, I would ask “Where did you get your findings?” “How do you know?” These questions assumed that I knew what was right from wrong. As the intervention continued, I thought deliberately about being curious so I changed the language I used. Instead, I asked questions such as “Were there any differences between the information each source provides?” “Can you help me understand these findings?” Asking these questions put the authority back to the students as experts teaching me what they found in their research projects (McLaughlin, 2017).

There was also a shift in terms of the responses, behaviour, and confidence levels of the three students when the first and last sessions were compared. Their confidence increased with the quality of their responses to my questions. In the first session, all three students were really just answering the questions without connecting or expanding or challenging what the other person was saying. It was more like me interviewing them and not them having a conversation with each other about their learning stories. However, as time went by, students started to enjoy the process and were looking forward to Thursday to tell me their stories.

The effect that this conversation series had on the students was significant. Their subsequent academic results within the unit of study indicated success as all three students passed while one student achieved with Merit. The students reflected on struggling alone and how the conversations changed that. They also revealed the fact that now they have conversations in places such as bed, and are constantly asking questions to better understand concepts. They have also changed the conversations within their class, and other students have embraced the idea because they are able to learn from each other. The teacher also noted what was happening and asked the girls where they got the idea from.

Ruru et al.’s (2013) adaptive mentorship model fits well with this mentoring approach because the amount of support I gave was dependent on students’ abilities to converse. My responses to their questions were modified to suit their level of confidence. The approach encouraged me to recognise and readjust the language I used in order to give authority to students as experts rather than learners. As a result, they created new knowledge for themselves. As mentors, sometimes we are afraid to expose our vulnerabilities. However, McLaughlin (2017) encourages us to show this side as she believes “asking, rather than knowing is really at the heart of intelligent enquiry” (p. 1).

Reflection and implications

The next step for me as a teacher is developing my questioning abilities to a stage where I am operating from an autonomous position. There is a lot of literature around different types of questioning approaches and the more I practise the better I will become at it. Sometimes I think my only job is to be the expert in the room, but I have learned a lot by being vulnerable. I reflected on how the language I used played a vital part in positioning myself as a learner instead of a mentor/coach. This way, rather than teaching, I am facilitating the students’ learning by activating the knowledge that is locked away in their minds.

It is vital for teachers to make sure they set high and achievable expectations and do not fall into the deficit theorising of Pacific students. High expectations are identified by students through the relationships they build with each Pacific student in the class. Showing vulnerability can be a way of forming connection with students as students need to relate to what you say or do as a teacher. Everyone has a story to tell. Once the connection is established, the relationship will bloom and results will take care of themselves.

Asking the right questions may sound easy, but can be complicated at the same time. Curious questioning was the key that opened the doors of the students’ minds to express their feelings through their stories. I found in this intervention that the more I became curious about what they were learning, the more they were able to connect the dots in terms of the stories they were telling each other. As educators, we have an unspoken expectation coloured by society’s views that we teachers are the source of knowledge and it is vital for us to educate while learners learn. There is some truth in this; however, I have found it most rewarding to listen to facilitate learning in this intervention. Although I am not suggesting that we neglect teaching—since it is our primary job—but I am proposing that we need to rethink it.

The students’ reflections about the intervention have given me the confidence to solidify this mentoring approach and start putting it into practice starting at my own school. I know from my own experiences as a learner that this approach works. The intervention also found success in re-orientating the thinking of the three students. It will be interesting to see this mentoring tool on a bigger scale such as a whole class or wider group of people.

Conclusion

This action-research intervention helped a small group of students realise their own potential during ongoing mentoring conversations. Talanoa was used effectively to guide conversations and provide the information needed for the project. The chosen skills were utilised successfully with the students not only achieving the credits needed for their record of learning from this unit, but also taking what they have learned through this intervention and applying it in their learning in the classroom environment and beyond. This caused a shift in the thinking of students as well as the teacher towards this fresh approach to learning. This use of curious questions within mentoring conversations may be of interest to other teachers within New Zealand secondary schools working to increase the confidence of Pacific learners or other students.

References

Abdullah, J., & Stringer, E. (1999). Indigenous knowledge, indigenous learning, indigenous research. In L. Semali & S. Kincheloe (Eds.), What is indigenous knowledge? Voices from the academy (pp. 143–155). New York, NY: Falmer Press.

Airini, Anae, M., & Mila-Schaaf, K. (2010). Teu le va: Relationships across research and policy in Pasifika education. Report to the Ministry of Education. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Airini, Curtis, E., Townsend, S., Rakena, T., D., Sauni, P., Smith, A. et al. (2011). Teaching for student success: Promising practices in university teaching. Pacific–Asian Education, 23(1), 71–90.

Anae, M., Coxon, E., Mara, D., Wendt-Samu, T., & Finau, C. (2001). Pasifika education research guidelines. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Brockbank, A. & McGill, I. (2006). Facilitating reflective learning through mentoring & coaching. London: Kogan Page.

Chu, C. (2009). Mentoring for leadership in Pacific education. Doctoral thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington.

Chu, C., Abella, S. I., & Paurini, S. (2013). Educational practices that benefit Pasifika learners in tertiary education. Wellington: Ako Aotearoa, National Centre for Tertiary Teaching Excellence. Retrieved from http://akoaotearoa.ac.nz/pasifika-learners-success

Delpit, L. (2006). Other people’s children: Cultural conflict in the classroom. New York, NY: New Press.

Farrelly, T., & Nabobo-Baba, U. (2014). Talanoa as empathic apprenticeship. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 55(3), 319–330.

Farruggia, S., Bullen, P., Davidson, J., Dunphy, A., Solomon, F. & Collins, E. (2011). The effectiveness of youth mentoring programmes in New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 40(3), 52–70.

Fletcher, J., Parkhill, F., Fa’afoi, A., Taleni, L., & O’ Regan, B. (2009). Pacific students: teachers and parents voice their perceptions of what provides supports and barriers to Pacific students’ achievement in literacy and learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(1), 24–33.

Gegeo, D., & Gegeo, K. (2000). The critical villager: Transforming language and education in Solomon Islands. In J. Tolletson (Ed.), Language policies in education: Critical issues (pp. 1–30). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erbaum.

Gorinski, R., & Abernathy, G. (2007). Māori student retention and success: Curriculum, pedagogy and relationships. In T. Townsend & R. Bates (Eds), Handbook of Teacher Education (pp. 229–240), Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer.

Grant, A., & O’Connor, S. (2010). The differential effects of solution-focused and problem-focused coaching questions: A pilot study with implications for practice. Industrial and Commercial Training, 42(2), 102–111. https://doi.org/10.1108/00197851011026090

Halapua, S. (2008). Talanoa process: The case of Fiji. Honolulu: East West Centre.

Jones, A. (1991). “At school I’ve got a chance.” Culture/privilege: Pacific Islands and Pakeha girls at school. Palmerston North: Dunmore Press.

Manu’atu, L., & Kepa, M. (2002, October). Towards reconstituting the notion of study clinics: A Kakai Tonga Tu’a community based educational project. Presentation given to the First National Pasifika Bilingual Education conference, Auckland.

Mara, D. (2019). Towards an authentic implementation of Teu Le Va and Talanoa as Pacific cultural paradigms in early childhood education in Aotearoa New Zealand. In A. Gunn & J. Nutall (Eds), Weaving Te Whāriki (3rd ed., pp. 91–105). Wellington: NZCER Press.

McLaughlin, D. (2017). Curious questions. Insights Magazine, Fall, 38.

Ministry of Education. (2016). Leadership practices supporting Pasifika student success: Otahuhu College case study. Wellington: Author.

Ministry of Education. (2018). Tapasā, a cultural competencies framework for teachers of Pacific learners. Wellington: Author.

New Zealand Qualifications Authority. (2018). Annual report on NCEA and New Zealand scholarship data and statistics 2017. Retrieved from https://www.nzqa.govt.nz/studying-in-new-zealand/secondary-school-and-ncea/find-information-about-a-school/secondary-school-statistics/

Pelan, V. (2012). The difference between mentoring and coaching. Talent Development Magazine, February, 34–37.

Rakena, T., Airini, & Brown, D., (2016). Success for all: Eroding the culture of power in the one-to-one teaching and learning context. International Journal of Music Education, 34(3), 285–298. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761415590365

Ruru, D., Sanga, K., Walker, K., & Ralph, E. (2013). Adapting mentorship across the professions: A Fijian view. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, 11, 70–93.

Samu, T. W. (2015). The ‘Pasifika umbrella’ and quality teaching: Understanding and responding to the diverse realities within. Waikato Journal of Education, Special 20th Anniversary Collection, 129–140. https://doi.org/10.15663/wje.v20i3.229

Sanga, K., & Chu, C. (Eds.). (2009). Living and leaving as legacy of hope: Stories by new generation Pacific leaders. Wellington: He Parekereke Institute for Research and Development in Maori and Pacific Education, Victoria University of Wellington.

Sanga, K., & Reynolds, M. (2018). Melanesian tok stori in leadership development: Ontological and relational implications for donor-funded programmes in the Western Pacific. The International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives, 17(4), 11–26.

Sanga, K., & Walker, K. (2012). The Malaitan mind and teamship: Implications of indigenous knowledge for team development and performance. The International Journal of Knowledge, 11(6). https://doi.org/10.18848/1447-9524/CGP/v11i06/50213

Schumacher, D. (1998). The transition to middle school (Report No. EDO-PS-98-6). Washington, DC: Clearinghouse on Elementary and Early Childhood Education.

Si‘ilata, R., Samu, T., & Siteine, A. (2017). The va’atele framework: Redefining and transforming Pasifika education. Handbook of Indigenous Education, 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-1839-8_34-1

Si‘ilata, R. K. (2014). Va‘a tele: Pasifika learners riding the success wave on linguistically and culturally responsive pedagogies. Doctoral thesis, The University of Auckland, Auckland. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/2292/23402

Si‘ilata R., Samu T.W., & Siteine A. (2018) The Va‘atele Framework: Redefining and Transforming Pacific Education. In E. McKinley & L. Smith (Eds), Handbook of Indigenous Education (Vol. 2, pp. 907–936). Springer, Singapore

Taleni, T. O., Macfarlane, A. H., Macfarlane, S., & Fletcher, J. (2017). O le tautai matapalapala: Leadership strategies for supporting Pasifika students in New Zealand schools. Christchurch: University of Canterbury.

Tamayose, A., & De Silva, S. (2017). How did Polynesians way-finders navigate the Pacific Ocean? Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m8bDCaPhOek

Taufe’ulungaki, A. (2009). Tongan values in education: Some issues and questions. In K. Sanga & K. Thaman (Eds.), Re-thinking education curricula in the Pacific: Challenges and prospects (pp. 125–136). Wellington: He Parekereke Institute for Research and Development in Māori and Pacific Education.

Thaman, K. H. (1993). Culture and the curriculum in the South Pacific. Comparative Education, 29(3), 249–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305006930290303

Thomas, W. & Smith, A. (2009). Coaching Solutions. London: Bloomsbury.

Vaioleti, T. (2006). Talanoa research methodology: A developing position on Pacific research. Waikato Journal of Education, 12, 21–35. https://doi.org/10.15663/wje.v12i1.296

Talitiga Ian Fasavalu is an educator working in Physical Education and Health at a secondary college in the Wellington region. He recently completed his Masters of Education on a TeachNZ scholarship study award at Victoria University of Wellington. He is passionate about changing the learning experiences of Pasifika students in schools with the hope that this will be reflected in their academic and personal success. His research interests include mentorship and the relevance of Pacific thinking to education.

Talitiga Ian Fasavalu is an educator working in Physical Education and Health at a secondary college in the Wellington region. He recently completed his Masters of Education on a TeachNZ scholarship study award at Victoria University of Wellington. He is passionate about changing the learning experiences of Pasifika students in schools with the hope that this will be reflected in their academic and personal success. His research interests include mentorship and the relevance of Pacific thinking to education.

Email: talifasavalu@gmail.com

Kate Thornton is an associate professor at Victoria University of Wellington who teaches a postgraduate course in coaching and mentoring for educational leadership.