Creating collaborative effectiveness

One school’s approach

SARAH MARTIN AND CHRIS BRADBEER

Key points

•For teachers shifting into innovative learning environments the time spent developing an understanding of effective collaboration and what is important to work on together, is time well spent.

•Developing a collective understanding of what we are aiming for in “synergetic” teams helps to identify areas for team and individual growth.

•Building teacher capacity to manage conflict is an important focus for ongoing teacher professional learning and supports teachers to address issues that arise.

Creating the conditions for effective teacher collaboration has been seen as a critical component of the work that leaders have been engaged in at Stonefields School since it opened in 2011. Acknowledgement that collaboration can be an opportunity, but also be challenging at times, has informed elements of ongoing professional learning. One of these has been in growing teacher capacity to have sensemaking conversations, a disposition seen as especially relevant when teachers are working together in shared innovative learning environments.

Introduction

As Michael Fullan (2002) notes, “the single most important factor common to successful change is that relationships improve. If relationships improve, schools get better. If relationships remain the same or get worse, ground is lost” (p. 17). Keeping in mind that a prime reason for creating a culture of collaborative relationships and responsibility is, as DuFour and Mattos (2013) note, to impact positively on student outcomes, the relational work we do as leaders of change should be foremost in our thinking. Creating and maintaining relationships within schools, and between teachers, is a critical element of positive school-wide change. Yet the web of relationships embedded within schools is intricate and complex. As we develop greater understandings of teacher collaboration within schools, accentuated by a shift into innovative learning environments, the teacher–teacher relationship component becomes increasingly highlighted. This, as we have discovered at Stonefields School, has necessitated an exploration of the nature of highly effective teams, along with the design of frameworks to support the growth of collaborative capacity.

Background

Stonefields School originally opened its doors to 48 foundation learners and 10 teachers in 2011. The school is made up of a series of learning hubs where around 75 learners and three teachers learn together. Five years on, the school has in excess of 500 learners and 30 teachers who work and learn collaboratively within a series of open innovative learning environments that we call hubs. An important decision early on was that teachers wouldn’t operate in the hub in isolation and have their “own class”. Instead, the intention was to pool teacher strengths, be purposeful, and use evidence about how to best organise the learning, so that we could best serve the needs of the cohort of learners.

The school is on track to grow to 800 learners. One consequence of this rapid roll growth is the need to induct significant numbers of teachers each year, and with it foster a growing awareness of the role that teacher collaboration plays. Clearly, collaboration is instrumental to the organisation’s success on many levels—in our view it is the most significant contributor to the school organisational culture. Unsurprisingly, though, working so closely with colleagues comes with its benefits and challenges. The small stuff, often quite low level, can have huge “get up your nose” potential. How tidy, how timely, or how your hub colleagues do a wall display has the potential to cause dissonance, or what we have simply come to term rub amongst team members. Consequently the reluctance or inability to address what Ronald Barth (2002) terms “non-discussables” can have a detrimental impact on the organisational culture. For Barth, non-discussables are:

subjects sufficiently important that they are talked about frequently but are so laden with anxiety and fearfulness that these conversations take place only in the parking lot, the rest rooms, the playground, the car pool, or the dinner table at home. Fear abounds that open discussion of these incendiary issues—at a faculty meeting, for example—will cause a meltdown. (p. 8)

What led to a focus on growing collaborative capability?

Between 2011 and 2013 important learning began to emerge as we started to notice those teams that stood out as operating highly effectively. We were intrigued by the systems, conditions, ways of being and operating that led to their effectiveness. It became obvious that these teams had mechanisms and systems in place to surface and talk about the non-discussables. The teams that were less effective didn’t appear to have the same capacity to talk about the “hard to talk about” things. Often, potential conflicts or problems were avoided from fear of hurting another person’s feelings. Sometimes small things like tidiness created great tension, as did different standards and expectations between individuals. What resulted was increased frustration within teams, because time would elapse with issues being left unaddressed and unresolved.

Building collaborative capacity was identified as a priority as the predicted roll growth continued. Strategic goals were set in 2014 to address the challenge ahead, and a collaborative inquiry began. The inquiry question was “How do we accelerate a team’s function into a highly synergetic state?” – where “synergy” here is taken to mean a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts (Senge, 2006).

A group of interested staff unpacked what we were aiming for in a “synergetic team”. We asked ourselves questions such as the following.

•How much time do you spend meeting as a team?

•How do you work to your team strengths?

•How do you organise what you do together?

As the dialogue developed, underpinning principles of team effectiveness began to emerge. Through this process a key contributing factor came to be constantly highlighted—the management of conflict in the team. This insight led to the realisation that the key capability of a team member working so intimately with hub colleagues is to be able to engage in conversations that might be avoided. Often these conversations have been couched in terms of “hard to have”, or “courageous” conversations—a language that we felt potentially created a barrier or left a negative connotation. At this point Gaye Greenwood influenced our thinking through her PhD work (Greenwood, 2016) on making sense of conflict management in the workplace. She introduced us to the term sensemaking, theorised as a response to ambiguity, uncertainty, and change (Weick, 2001).

Importance of collaborative capability (sensemaking)

From Weick’s (2001) definition we came to understand sensemaking as the conversation that needs to occur when there is a point of difference or a point of “not understanding” between colleagues. Coupled with this is a need to grow an awareness of the conversation that needs to be had, when it needs to happen, and the right person to have it with. Audits of hub collaboration suggested that some teams engaged in sensemaking in ways that other teams found challenging. But if this capacity forms the crux of effective teacher collaboration, it is not something that we can afford to leave to chance. The capacity to give and receive trust, to sensemake and be open, bridges a threshold that helps to move from the ‘I’ space to the ‘we’ space—a critical component of working together in a shared innovative learning environment. For some teachers this is easy to do; for others, it constitutes a more challenging area of personal and professional growth. Perhaps ego might get in the way of team members transitioning and being comfortable and successful in the “we” space?

By way of example, some ways into sensemaking conversations might be:

“Can you tell me more about why you think that?”

“I’m not sure I understand. Could you explain that another way?”

“Let me see if I’m understanding this. So you’re saying…”

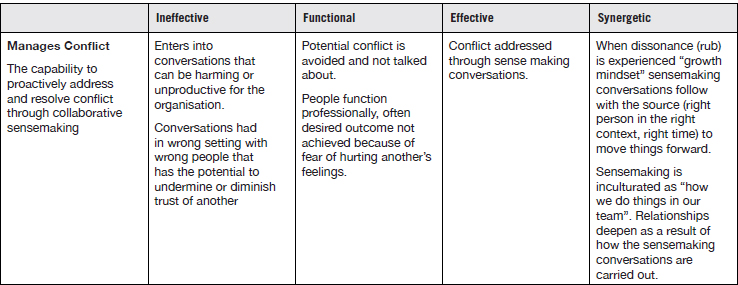

The capacity to have sensemaking conversations now forms one of a set of key collaborative teacher dispositions that we have developed for self and team reflection. One of the personal development pieces we are seeking is illustrated in the continuum in Table 1.

Our inquiry and evidence suggests that that there is a significant impact on outcomes for learners when teams operate at a more “synergetic” level. After conducting many interviews with teams that function at a synergetic level we have tried to identify additional “effectiveness indicators” that underpin the capacities and conditions that support this collaboration. As our collaborative inquiry deepened, further questions were interrogated.

TABLE 1. COLLABORATIVE TEACHER DISPOSITIONS: MANAGES CONFLICT

•Is there a certain time frame required for a team to develop to a deep synergetic level?

•Given the tools can all teams move to a “synergetic” level?

•Are there certain personality traits and types that enable a team to become synergetic?

Honing in on key elements of collaboration

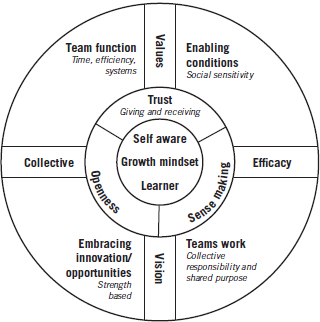

As the group of interested staff continued to inquire together, the elements underpinning a successful synergetic team became clearer. At the heart of a highly functioning team are conscious, self-aware individuals. They are open to learning, they continue to learn and to further their own learning for the betterment of self and the learners they serve. They are constantly growing and evolving their self-awareness through reflection, self-questioning, and a drive to self-improve. Mental models are evaluated as learning continues. The outlook of an individual who contributes constructively in a team is one of a growth mindset—they are optimistic, open, and reflect on what can be learnt, changed, and adapted in challenging times. These dispositions are seen as critical when transitioning from an “I” space to a “we” space.

This thinking went on to form the central component of a model that the inquiry group developed (see Figure 1). The model outlines four key elements to a team’s success: its function, the conditions (culture), the work the team does together, and how it operates in a strength-based way. Once it had been created, the model helped to identify areas where professional learning time might be invested most purposefully.

FIGURE 1. COLLABORATIVE FRAMEWORK

The model also prompted thinking about being more disciplined around the tasks on which teachers collaborate. As Hansen (2009) notes, disciplined collaboration is the “practice of properly assessing when to collaborate (and when not to) and instilling in people both the willingness and the ability to collaborate when required” (p. 15). There needs to be a reason to collaborate. The last thing teachers need is to be meeting and spending time collaborating when it is not fit for purpose. As time goes on, teams become very savvy about what they will and won’t collaborate on.

We have found that the success of a team can be quite immediate if time and energy is put into building the function and culture of the team. Flexibility about when a team is going to meet, what it is going to spend time on, and who is going to take responsibility for what, are all important routines to establish. “Sharing the load”, along with individuals following through with what they said they would do, are critical to the wider team integrity and trust. We have watched the most synergetic teams provide time and forums to have conversations about how individuals like to be supported, how they like to be communicated with—“elephant time” on meeting agendas, where potential elephants growing within the hub are addressed and worked through.

The teams that initially invest time and energy in creating collaborative norms underpinning “how they do things around here” flourish. The culture of a team is critical when faced with a crisis (e.g., challenging student behaviour, learners not progressing). Although a crisis would not be manufactured, we do believe such an event can deepen trust, effectiveness, and overall team bonds between the members of a hub team.

A framework of matrices has subsequently been developed to inform individual and team effectiveness and stimulate conversation and action about where the team aspires to be. Each row of the matrix matches a part of the model.

Where are we in 2016?

Once again we have had a number of new staff to induct in 2016. The development and refinement of the collaboration framework has been invaluable. It has been used as a significant part of our whole staff professional learning and induction. The collaboration framework helps to make tangible what has historically been hard to pinpoint. Development of additional continua have helped teams evaluate their effectiveness and to start conversations that typically have been put in the too-hard basket. They have also enabled forward-focused conversations about where teams are aspiring to be.

The framework makes the collaboration we are aiming for visible. Our staff survey data would suggest that the longer people have been at Stonefields the greater their comfort in having the sensemaking conversations that need to be had. Our goal is to develop all teachers’ comfort in being uncomfortable—to grow individuals’ and teams’ comfort with challenge, provocation, and dialogue, in order to have a greater collective impact on outcomes for our learners. John Hattie at the recent 2016 global chat said that “The essence of teachers’ professionalism is the ability to collaborate with others to maximise impact”.

We are starting to make some early correlations between “synergetic teams” and their ability to accelerate outcomes for learners. We are pleased to say that this is now enculturated in the “way we do things around here” at Stonefields. The culture is purposeful, focused on causing learning for every learner, and collaborating to reap the benefits of collective efficacy.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Rose Hipkins for her valuable feedback and encouragement. Thanks also to Gaye Greenwood for sharing her wisdom and expertise, particularly in the area of sensemaking and conflict.

References

Barth, R. (2002). The culture builder. Educational Leadership, 59(8), 6–10.

DuFour, R., & Mattos, M. (2013). How do principals really improve school? Educational Leadership, 70(7), 34–40.

Fullan, M. (2002). The change leader. Educational Leadership, 59(8), 16–20.

Greenwood, G. (2016). Transforming employment relationships? Making sense of conflict management in the workplace. Unpublished PhD thesis, Auckland University of Technology.

Hansen, M. (2009). Collaboration: How leaders avoid the traps, create unity and reap big results. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press.

Hattie, J. (2016, February 12) Global dialogue webinar.

Senge, P. (2006). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organisation (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Random House.

Weick, K. E. (2001). Making sense of the organisation. New York, NY: Blackwell Publishing.

Sarah Martin is the foundation principal of Stonefields in Auckland. She is a forward thinking educator with a real commitment to improving outcomes for all learners. Sarah is passionate about future focused approaches to learning as well as strategies for creating organisational change.

Sarah Martin is the foundation principal of Stonefields in Auckland. She is a forward thinking educator with a real commitment to improving outcomes for all learners. Sarah is passionate about future focused approaches to learning as well as strategies for creating organisational change.

Email: sarahm@stonefields.school.nz

Chris Bradbeer is an associate principal at Stonefields. He is currently engaged in research focused on the opportunities engendered by the provision of new learning spaces, and in particular the nature of collaborative teacher practice.

Chris Bradbeer is an associate principal at Stonefields. He is currently engaged in research focused on the opportunities engendered by the provision of new learning spaces, and in particular the nature of collaborative teacher practice.

Email: chris@stonefields.school.nz