Editorial

Tēnā koutou rangatira mā.

Te toi whakairo, ka ihiihi, ka wehiwehi, ka aweawe te ao katoa. Artistic excellence makes the world sit up and wonder.

This whakataukī gives inspiration to Issue 2, as it does for the New Zealand Curriculum (2007, p. 20), Creative New Zealand, and many involved in Ngā Toi Māori and the arts sector.

The Arts in the New Zealand Curriculum emphasises that the arts disciplines offer students unique opportunities for imaginative and innovative thought and action, for emotional growth, and for deeper understandings of cultural traditions and practices in New Zealand and overseas. (Ministry of Education, 2000, p. 5)

While only one article examines Arts as a learning area, the full spread of Issue 2 is rich in graphics. Authors supplied photos, screenshots, graphs, or other images to include with their text. Art and design bring an added dimension to the journal’s written text.Set’s online subscribers are treated to full colour.

The opening article directly addresses the power of visual art and design. Tongan artist and educator Dagmar Dyck is the deputy principal, curriculum leader, and lead arts teacher at Sylvia Park School. Her master’s studies explored how senior secondary visual arts programmes in Aotearoa New Zealand support Pasifika students’ success in culturally sustaining ways. Dagmar’s diagrammatic analyses demonstrate how art teachers encouraged students to draw from their community relationships, cultural values, personal experiences, and political viewpoints throughout their creative process. The artworks from four students are presented, all of which I find both stunning and thought-provoking. I also acknowledge feeling uncertain about how clearly my palagi eyes see into the artists’ meaning making. Dagmar speaks of students’ poignant experiences of external examination, which,

exposed them to strangers who lacked the cultural and personal knowledge about the particular circumstances and struggles of Pasifika students… Since in visual arts the students’ artworks are based on their personal narratives and life experiences, this leaves them feeling vulnerable to examiners with little understanding to the contextualisation of their works. (p. 10)

Mark Osborne’s article, “Acts of Magic—Prototyping Innovative Learning Environments”, turns to teachers’ own representations of the future they wish to create. A co-ordinate graph plots the different ways in which schools might mock-up flexible learning spaces. Mark weighs up pros and cons associated with how expensive and enduring each prototype might be. Photos show teachers huddled around drawings and models of 3D-printed furniture as they imagined, even dramatised, how learning might unfold. The article identifies that trialling pedagogy and systems can be as useful as physical exemplars.

The next article looks at digital representation and gamification. Principal Lou Reddy and academics from four separate universities tested a beta version of a mobile application (app) to support Positive Behaviour for Learning (PB4L) School-Wide.1 Data about student behaviour is captured and reported using digital profiles and award badges. The article includes screenshots of the app’s menus and emblems, a bar graph showing usage patterns, as well as a word cloud. Results of the trial suggest that the app, Ka Pai, aligned with the school’s values and strategic goals and strengthened teacher pedagogy. The next article also includes a screenshot of a new app, SMATA, which enables teachers to collect observation data, reflect, and graph against learning areas.

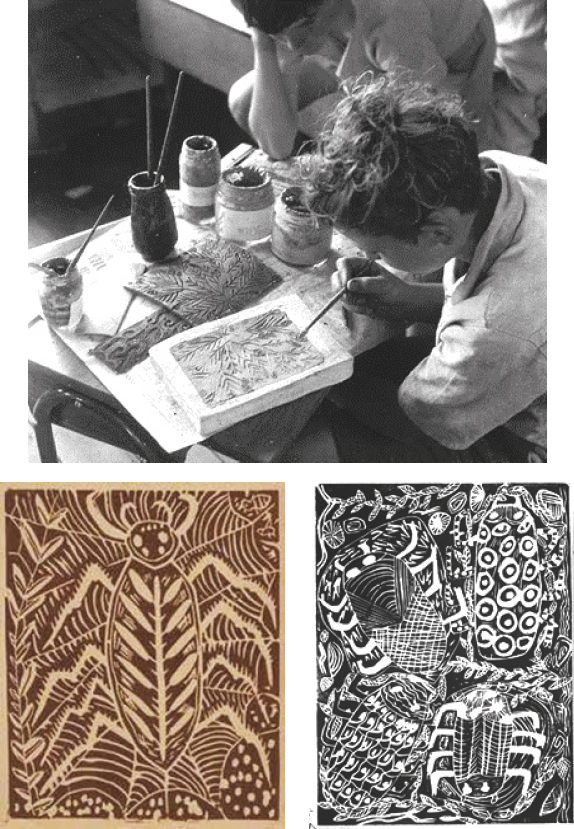

Visual arts/art history head of department Kirsty Grieve worked with Bevan Holloway, a professional learning and development provider, prior teacher, and founder of SMATA, to prepare “Creative Agency in Action” for Set’s Practitioner Inquiry section. Their article illuminates the background thinking and outcomes from an innovative cross-curricular course centred on student agency and relational pedagogy. Infographics depict a design-thinking model, designed by the teachers and students, to help generate metacognitive awareness throughout. The photo of students engrossed in their personal projects surrounded by wood cut prints reminds me of Elwyn Richardson and the Early World of Creative Education in New Zealand (MacDonald, 2016).

In fact, a posthumous appreciation of teacher Elwyn Richardson makes for a nice segue into He Whakaaro Anō, where the topic is climate-change education. Elwyn was renowned for intertwining art and science in an uber local, student centred, environmentally focused curriculum.

As a scientist who had learned to love his botanical specimens as a child, Richardson found that he had a personal aesthetic desire to understand the beauty of nature, and he taught so his children were able to discover, recognise and witness these values … [He] sought and struggled to find a path that would bring together the scientific and the aesthetic. (Macdonald, 2016, p. 99)

Elwyn is also a protagonist in The HeART of the Matter (Bieringa, 2016), a documentary that Māori TV recently screened about “postwar education programmes that put Māori arts into the classroom” (Māori TV, 2021). If you haven’t seen the film or read the book, I highly recommend both. A written editorial cannot do justice to Elwyn’s own poetic quotes, the compilation of his students’ vivid artworks, nor documentary footage. What I’m left with is a wondering about the potential global impact of students everywhere having spacious learning opportunities, which allow them to deeply connect with the natural world and indigenous cultures, all with an inquiry mindset and creative spirit.

PHOTOS COURTESY OF MARGARET MACDONALD (2016)

Thomas Everth and the University of Waikato Climate Change Educators network have more-than-pondered potential pathways between student learning and global environmental forecasts. Their article adapts their original submission to He Pou a Rangi Climate Change Commission. The Waikato authors address the role of education in achieving the government’s goal of a carbon-zero future. As they say, “building capacity to meet the challenge requires a cohesive and agile climate-change education strategy” (p. 34). They argue for teacher professional development towards empowering pedagogies and centring both mātauranga Māori and Western climate science in the curriculum. The article provides readers with a strong follow on from Set’s special issue, Climate Change, Education and a Sustainable Future (Eames, Bolstad and Roberts, 2020).

If you wish to catch up on how education features in the post-submission final advice from the Climate Change Commission (2021), you might like to read Rachel Bolstad’s June 2021 blog.2 Since then, in August, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released a concerning report (IPCC, 2021).3 Its predictions are intense. A glass-half-empty reading might leave one feeling dispirited. However, deliberately choosing to see the glass-half-full (as teachers must) invigorates commitment to the carbon-zero cause and shows the vital impact of positive human action.

For teachers and students feeling the dual weight of climate change and COVID-19, please remember Te Rito Toi.4 The online resource supports educators to promote wellbeing after traumatic events. It is based on research about the role of the arts in making meaning and renewing hope. As co-founder Peter O’Connor’s puts it, the arts can provide a “bridge to a better future” (2020).

Visual representation and artistic expression enable students to work through problems in rich ways. For schools, it is important to consider where assessment fits with non-text ways of thinking and doing. Assessment News offers some insight. Jonathan Fisher leads the team that designs the Assessment Resource Banks (ARBs). A recent online development has been the addition of an interactive drawing tool. The ARBs team “wanted to provide less constrained ways for students to express their thinking” (p. 39). Jonathan outlines a range of resources that utilise the web-based drawing tool-panel in several learning areas. He points to their benefits while also acknowledging that the power of sketching with pencil on paper should never be underestimated. Pragmatically, “There is also nothing stopping students working in a hybrid fashion with off- and online” (p. 41).

To end, I want to put in a final plug for Ngā Toi in Te Marautanga o Aotearoa (2008) and The Arts in The New Zealand Curriculum (2007), including the learning areas’ abilities to integrate effectively with others in authentic contexts. Remember,

The arts develop the artistic and aesthetic dimensions of human experience. They contribute to our intellectual ability and to our social, cultural, and spiritual understandings. They are an essential element of daily living and of lifelong learning. (Ministry of Education, 2000, p. 9)

In te ao Māori,

He toi whakairo, he mana tangata. Where there is artistic excellence, there is human dignity.5

May we collectively walk a path of integrity as we find our way through pressing crises in human and planetary health. Full strength to the teachers and school leaders who are responsible for crafting learning opportunities at such a pivotal time.

Ngā mihi nui ki a koutou katoa. As always, our thanks go to our authors and our readers. Gratitude also to all those behind the images contained in this issue, artists, designers, app developers, photographers, and their willing subjects.

Josie Roberts

Notes

1.For a short video and text about Positive Behaviour for Learning School-Wide look up https://pb4l.tki.org.nz/PB4L-School-Wide/What-is-PB4L-School-Wide

2.The blog The Climate Change Commission updated its advice, what does it say now? can be found at https://www.nzcer.org.nz/blogs/climate-change-commission-updated-its-advice-what-does-it-say-about-education-now

3.Stuff’s climate editor, Eloise Gibson, provides a readable New Zealand-centric summary of the report at https://www.stuff.co.nz/environment/climate-news/126014839/planetary-healthcheck-delivers-unprecedented-terrifying-picture?rm=a. The IPCC’s own summary of headline statements is here: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_WGI_Headline_Statements.pdf

4.Te Rito Toi is freely available at www.teritotoi.org

5.This whakataukī, referenced in the NZQA’s (2014) Māori Performing and Creative Arts needs analysis report, illustrates “how, through Ngā Toi Māori, people young and old, are able to artistically express and articulate not only their dreams and aspirations, but also those of whānau, hapū, iwi and hapori” (p. 12). The report fed into the development of the current New Zealand Certificates in Ngā Toi Māori, with Levels 3–6 now under review in 2021. The whakataukī also titled Waiheke’s Matariki 2021 art exhibition in recognition of its reference to “how the making of art relates to and enriches the well being of humankind” (see https://www.waihekeartgallery.org.nz/whats-on/exhibitions/matariki-2021-he-toi-whakaaro-he-mana-tangata/).

References

Bieringa, L. (Director). (2016). The HeART of the Matter [Film]. Blair Wakefield Exhibitions.

Eames, C., Bolstad, R., & Roberts, J. (2020). Editorial. Set: Research Information for Teachers, (3), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.18296/set.0179

He Pou a Rangi Climate Change Commission. (2021). Ināia tonu nei: A low emissions future for Aotearoa. [Advice to the New Zealand Government on its first three emissions budgets and direction for its emissions reduction plan 2022–2025.] https://www.climatecommission.govt.nz/our-work/advice-to-government-topic/inaia-tonu-nei-a-low-emissions-future-for-aotearoa/

IPCC. (2021). Climate change 2021: The physical science basis. Cambridge University Press.

MacDonald, M. (2016). Elwyn Richardson and the early world of creative education in New Zealand. NZCER Press.

Ministry of Education. (2008). Te marautanga o Aotearoa. Author.

Ministry of Education. (2007). The New Zealand curriculum. Learning Media

Ministry of Education. (2000). The arts in the New Zealand curriculum. Author.

Māori TV. (2021). The heart of the matter. https://www.maoritelevision.com/shows/feature-documentaries/S01E001/heart-matter

O’Conner, P. (2020). Te Rito Toi. https://www.teritotoi.org