Let’s talk about literacy

Preparing students for the transition to tertiary learning

LISA EMERSON, with KEN KILPIN and ANGELA FEEKERY

I have been teaching writing at university now for 25 years. Before the 1990s, academic writing skills were something universities expected students either to arrive with or to pick up by a process of trial and error. But now all universities offer writing training through learning support facilities of some kind—usually very underfunded (Cameron & Catt, 2013; Gilliver-Brown & Johnson, 2009). Some degrees require the completion of an academic writing paper.

Over the years I’ve taught writing in business, humanities, and education, before settling in the sciences. I now teach a large first-year course which most students enrolled in a BSc must complete, focusing on scientific writing and communication skills. Many of my students have avoided writing-rich subjects at school and so are somewhat surprised to be confronted with a writing teacher in their first semester of a BSc. The question they most often ask me is “what has writing got to do with science?”

Part of my motivation in teaching writing has been to spare students some of the anxieties of adjusting to academic writing by focusing on the literacy skills and processes they need. But it wasn’t until a few years ago that I realised that I’d missed two questions that are fundamental to teaching: where are my students coming from? What have they learned so far about academic literacy?

The catalyst for these questions came about when I was asked to run writing workshops for Year 13 scholarship students across the North Island. It was a joy to work with these motivated, engaged students. But even more significant for me were the conversations with the teachers who attended. I was surprised that the approach to writing I was teaching was new even to the English teachers. As we discussed writing further, I realised how little I knew about high-school literacy expectations or the learning environment to which my students were accustomed. Suddenly my students’ struggles and behaviour made more sense.

I began to canvas my colleagues: what did they know about NCEA and first-year students’ prior experience of learning? Nothing it seemed. Some had views (almost entirely negative), but they were based (if they were based on anything) on nothing more than their own children’s experience.

Nowhere, it seemed, were secondary and tertiary teachers having a conversation in the same room.

First steps

It was in this context that we won a Teaching and Learning Research Initiative bid to run a 2-year research project (2013–2014) to investigate the transition from high school to tertiary learning and literacy. The project focused on researching transitioning students from Year 13 to first-year tertiary study in five low- to mid-decile schools in the central North Island through a focus on academic literacy. (For more detailed discussion of the project, see Kilpin, Emerson & Feekery, 2014b.)

This article, then, is an introduction to our observations and the actions we took to begin a professional conversation about student literacy across the secondary–tertiary divide. We hope that it is also a clarion call or an invitation to teachers in both the secondary and the tertiary sectors: how do we find a way to extend this conversation?

Looking at the academic literacy gap

It is, of course, difficult to generalise our observations from five low-mid decile schools to the sector as a whole. But since our project ended we have shared our findings with a wide variety of schools, and the feedback suggests our findings resonate widely. The emphatic point we wish to make is this: the gap between secondary and tertiary education in terms of literacy and the learning environment is bigger than anyone is acknowledging. Three issues stand out.

The first issue is independent learning skills, a notion that lies at the very heart of tertiary education—and university education in particular. Students are expected to be independent learners from the moment they enter tertiary study. That is, they are expected to manage their time and study programme with little external monitoring. They are expected to be self-motivated, with an ability to assess, interpret, and complete assessment tasks independently and without a set of scaffolded tasks. Multiple opportunities to address an assessment point are rare.

The University of Auckland’s advice to enrolling students illustrates this position:

you are expected to work by yourself and to be a self-motivated learner. While you will have lectures, tutorials or seminars with a tutor, you are expected to work without their direct assistance. No one will follow up if you have not made a deadline for an essay—you will simply fail the paper. Nor will anyone check if you have read the relevant course material. You have complete responsibility for your study. (University of Auckland, n.d.)

We would question the extent to which the secondary school learning environment is preparing students for this expectation. Our observation was that students in the schools we worked with are generally provided by their teachers with highly structured and scaffolded assessment tasks, exemplars on which to model their own work, and pre-packaged information as the basis for their ideas—and that teachers are anxious about withdrawing this support, even at senior levels for their most able students. Pressured from multiple directions to produce high pass rates, teachers often provide the external motivation and pressure to ensure student success. A recurrent theme from our teachers was “we cannot risk our students failing”. One teacher explained:

if I do not get a good enough pass rate, there are consequences for me as a teacher, for the school, and for our community. The media and the ministry will be on our back. We just cannot take risks over outcomes.

Receiving a Not Achieved is often not a terminal grade, but rather a rationale for further assessment opportunities to deliver high levels of quality “student achievement”. One teacher observed, “I have one student who has passed a particular standard by doing it 10 times—and I really cannot say, in all honesty, that I know they understand the material.”

Many tertiary teachers, by contrast, are resistant to providing the kind of scaffolded support, exemplars, and processed information that students are familiar with from secondary school (Parsons, 2015). Most assessment points are end-points, something many transitioning students fail to understand. One of the tertiary teachers we interviewed expressed considerable confusion over students not submitting or failing assignments and asking her, “so what happens now?”

Modes of university course delivery underline the idea that universities expect students to engage as independent learners: first-year courses are commonly large, with many compulsory courses having rolls in excess of 400 students; much course material and support has to be accessed independently online; interaction with teachers is limited, and in some cases not encouraged. We would hope that the situation in New Zealand is better than in other parts of the world—a recent article in the New York Times, for example, commented that “for a majority of undergraduates, contact [with university teachers] ranges from negligible to non-existent” (Bauerlein, 2015)—but with the high administrative demands of managing large classes, tertiary teachers are not positioned to follow up on students who miss classes or fail to submit assignments.

Transitioning students, therefore, may arrive at a university that expects them to be something more than their prior learning experiences have prepared them for, and without the support to learn such skills. There is no gradual withdrawal of scaffolded support from teachers: the change in teacher attitudes and expectations hits all at once as students move from one sector to another: the training wheels drop off without warning and without someone to hold on to the back of the bike.

The second issue we observed was a significant disconnect between each sector’s views about the role of writing in relation to learning. We observed that, under pressure to pass students, product was prioritised over process in the senior secondary curriculum. Teachers told us that students resist writing, especially extended writing tasks, and in the face of this resistance teachers in some disciplines tended to limit written tasks.

Yet literacy capabilities are likely to be a key determinant of tertiary student success (Owen & Schwenger, 2009). In particular, we observed that the ability to write a sustained argument or analysis, of 1200 words or more, was critical to student success at tertiary levels.

The final observation we made in relation to the academic literacy gap was that secondary students in most disciplines were not developing the levels of information literacy expected for tertiary study. Students’ search skills were limited—often restricted to simple Google searches—and they (and their teachers) showed a lack of awareness of available databases; in many disciplines, they rarely engaged with primary texts; and they were insufficiently trained to avoid practices which might lead to plagiarism

By contrast, tertiary students are assumed to have effective information-search strategies, be able to read and critique long, dense primary texts, and then synthesise their findings and develop an argument in the context of the literature. Unless students enrolled in an academic writing course, the most support they could expect for developing those skills was an introduction to the library and a copy of the institution’s plagiarism policy.

One example illustrates these key findings: when we shared tertiary assessment instructions for first-year courses with secondary teachers, the most sustained response was astonishment—or horror. They observed that the assignments were longer and more complex (both conceptually and in terms of literacy demands) than anything their students would have encountered in Year 13, that they placed much heavier information demands on the students than they had expected, and they couldn’t imagine how their students could achieve the tasks in the absence of individualised support, scaffolding, and exemplars.

At the heart of the gap

At the heart of the gap our students must traverse lie fundamental misunderstandings between teachers across the sectors. Neither group fully understands the extensive changes the other sector has undergone within the last 10–20 years. None of the tertiary teachers we engaged with had read the revised New Zealand Curriculum (Ministry of Education, 2007) (NZC), or were aware of the recently completed standards realignment project, let alone considered the implications of the realignment for incoming students (for more information on the realignment, see Ministry of Education (2013, 29 January), and New Zealand Qualifications Authority (2013, 27 February)). They knew very little about the National Certificate of Educational Achievement (NCEA) or its assessment structures, but were willing to lay the blame for perceived falling standards at NCEA’s door. We would go further and suggest that tertiary institutions themselves understand little about literacy within the senior high school curriculum—for example, Auckland University’s recent requirement for increased English credits as a basis of enrolment demonstrates a misunderstanding of both how academic literacy is embedded in the senior secondary curriculum and the nature of the English curriculum (Radio New Zealand, 2014).

On the other side of the equation, most teachers we worked with based their assumptions about tertiary education on their own (often nostalgic) memories of university study. They demonstrated limited awareness of demands made on students’ independent learning skills by the digital nature of tertiary study, the explosion in information-literacy expectations, or the wide range of assessment genres. One teacher commented, “I feel ashamed. I have been telling my Year 13 students every year that I was preparing them for university: I was not.”

What the gap means

What we’re not suggesting here is that secondary teachers are not doing their job. Teachers are feeling the pressure to prioritise finding a way to pass students, to make visible the immediate effectiveness of their practice, and to ensure success for all students regardless of the multiple variables students present with. Within a culture of measurability and accountability, teachers are doing what they’ve been asked to do.

Neither are we suggesting (as tertiary institutions seem all too willing to assume given that, in most institutions and for most programmes of study, academic literacy courses are optional) that it’s the schools’ job to furnish transitioning students with all the requisite literacy skills to pass a degree programme. Such an expectation shows multiple misunderstandings of the nature of literacy: literacy skills are not generic, transferable, or context-free. Academic and disciplinary literacy should be taught within tertiary disciplinary studies since literacy cannot be separated from content, and must be engaged with at all levels of tertiary learning. Rather, literacy learning is a continuum, evolving according to the contexts in which it is practised. It is not a pre-determined kete of skills, the learning of which is the responsibility of pre-university teachers, nor does it terminate the minute students exit the secondary school system.

Nor are we suggesting that NCEA itself is responsible for the academic literacy gap. Unlike older qualifications, NCEA is not primarily a gatekeeper for the universities. It is not primarily an information or academic literacy curriculum. Rather, as the national qualification, it must be flexible enough to work for students exiting school directly into the workforce, into apprenticeships, to short-, medium-, and long-term vocational and professional studies, and into academic study.

So what are we suggesting?

First, we are suggesting that the pressures teachers face, and the particular aims for which NCEA is used, make it difficult for secondary teachers to look beyond the classroom to the future of their highest-achieving students, or to see a role for themselves in preparing students for those challenges.

Second, we are suggesting that that the two sectors are not communicating well enough to understand the extent and complexity of the transition students face, leaving students largely unsupported with complex cognitive tasks.

The third idea we want to suggest is that there is a fundamental misunderstanding about the nature of literacy, in both the secondary and the tertiary sectors, which is preventing a true embedding of literacy and learning across the two sectors.

Despite these pressures and constraints, what remains at the centre of the educational experience is the dynamic process of learning and knowledge building. For that experience to mean something more than retention, pass, and completion rates, teaching and learning must have advanced literacy instruction as an intrinsic feature of instructional design for senior secondary and for tertiary courses. So placed, disciplinary literacy instruction becomes more than a supplement to existing practices, or sets of strategies, activities, or plans that help “scaffold” students into content-area texts. It is rather, a deeper pedagogic approach that explains for teachers how and why students learn through text, what principles and theories of learning underpin decisions we make about literacy-centred instruction, how texts work to structure and instantiate knowledge discourses, and what metacognitive understandings students need to locate, retrieve, and critically use relevant information from challenging and unfamiliar texts. Educators need to know metacognitively why they are effective readers and writers of subject content texts. By understanding ourselves as readers, writers, and thinkers, we can begin to teach students how to critically think and use disciplinary texts to amplify content learning.

We need to embed a pedagogy of disciplinary literacy learning at the heart of subject and discipline instruction. A strong academic-literacy pedagogic foundation is the wellspring from which emerge effective instructional approaches and practices that actively immerse students in reading and writing for academic success. Our project revealed that placing disciplinary literacy at the pedagogic heart of educator practice challenges deeply held, historic discourses about what senior secondary schooling and university study are about.

So what do we do? Getting the conversation going

It is beyond the scope of this article to discuss in depth the methodology and processes of our project on smoothing the transition to tertiary literacy. More detail is provided in Kilpin et al. (2014a, 2014b). But, in brief:

•Our project used an action research methodology to build collaborations between the researchers and secondary and tertiary teachers.

•Stage 1 of the project (2013) focused on the secondary schools, through resourcing literacy leaders, peer support for teachers, and peer support for Year 13 students.

•Stage 2 of the project (2014) focused on resourcing and supporting dissemination of the project’s findings within the high schools, supporting students from Stage 1 through their first year of tertiary study, and disseminating findings within the tertiary sector. We also intended to undertake interventions at tertiary level.

Our first priority in Stage 1 was to connect the experiences, knowledge, and resources of people and institutions in both sectors in as many ways as possible. We started by getting the conversation going between the teachers in our five schools and tertiary teachers. We invited the schools’ literacy leaders and management to workshop meetings with tertiary teachers, to share our experiences of learning and teaching, and our beliefs and expectations of students. These conversations were deeply rewarding—and at times shocking!—for all concerned.

Our next priority was to bring students from the schools into the university to meet academic staff and engage in academic induction, with a particular emphasis on literacy skills. Students attended lectures and tutorials (so they understood how information was conveyed differently in the two forms of teaching), practised note-making in lectures, toured the university library and learnt about database searching, and worked with university assignments. Thus, the days went beyond the standard commercially driven expo approach, designed to attract students to our university. Our point was that whichever tertiary institution students attended, they would encounter the same literacy requirements, teaching approaches, and assessment systems, and need to be able to cope immediately.

Next, we brought secondary and university students together by implementing our peer tutoring scheme. In Stage 1, the peer tutors, who had completed two tertiary credit-bearing papers in peer support of writing, visited participating schools to work with students on writing and study skills, and to talk about university life and learning. In Stage 2 of the project, these peer tutors provided ongoing support for students from these schools in their first year of tertiary study at whatever tertiary institution they attended.

The final step in the “conversations” we hoped to initiate concerned helping tertiary staff to understand the literacy and learning context from which their transitioning students are emerging. As well as running workshops for tertiary staff in multiple venues—to introduce them to the findings of our research, to improve their understanding of NCEA and the literacy aspects of university entrance, and to suggest more effective ways of transitioning students into tertiary learning—we also hoped to work with teachers of first-year tertiary students to support students’ literacy transition.

However, we had only limited success in our engagement with the tertiary sector. The workshops we ran (funded by Ako Aotearoa) were well attended and led to fruitful and enthusiastic discussion (our explanations of NCEA and the realignment were clearly of great interest, particularly to university staff). But our invitation to become fully part of the project—to collaborate in the action research process and examine and revise their approach to assessment and student support—was not taken up. The reasons for this are unclear and require urgent investigation.

Resourcing the teachers

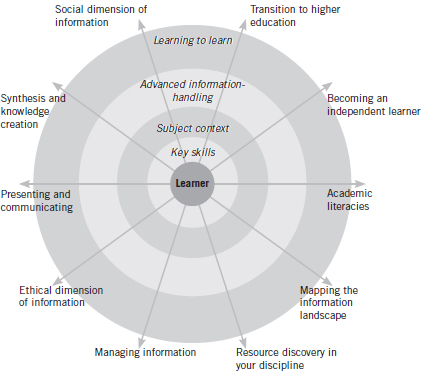

We continued to work in the secondary schools. Rather than seeing NCEA and NZC as ineffective vehicles by which to teach academic literacy, our project has developed teaching resources for academic information literacy development that integrate literacy into the content learning. To do this, we have adopted ANCIL— a New Curriculum for Information Literacy (Secker & Coonan, 2013) to reinterpret achievement standards and NCEA as enablers of academic and information literacy. The ANCIL framework, which is made up of ten strands that recognise the transition from senior secondary to tertiary learning (see Figure 1), provides teachers with “a series of practical steps through which to scaffold the individual’s [literacy] development” (Secker & Coonan, 2013, p. xxiii). ANCIL “advocates a close alignment with not only the intended learning outcomes, but also the assessment mechanisms and learning activities employed to achieve the outcomes” (Secker & Coonan, 2013, p. xxiii). In the second year of the project we identified these points of alignment to NZC and NCEA and trialled resources based on the ANCIL framework (Kilpin et al., 2014a) in our participating schools. In a recent workshop, teachers were asked to align the NCEA assessment standards with strands of the ANCIL curriculum to determine whether the assessments contained a deeper element of information literacy development that could be explicitly nurtured as students completed assessment tasks. At least five of the strands were implicit in the assessment standards, and teachers explored ways to extend these competencies in their students’ learning.

In this way, we are bringing literacy to the heart of our curricula and pedagogical practices. Our research continues to investigate both the effectiveness of integrating the ANCIL framework on either side of the transition, and the way ANCIL can be used to forge connections between subject curricula, university courses and the information/academic literacy skills upon which academic success depends. We hope to identify and resource effective pedagogical practices that will help secondary and tertiary teachers to orient their practice towards deeper literacy perspectives—and thus to enable an effective academic literacy transition for students. In other words, we hope this will be a way to close the gap between secondary and tertiary literacy.

FIGURE 1: ANCIL FRAMEWORK

(Secker and Coonan, 2013)

Conclusion

Throughout this project we saw significant change in teacher practices, in terms of encouraging independent learning and developing students’ literacy and information literacy capabilities. One teacher commented:

I saw my role as the teacher as being one of processing information for the students to make it more appealing and easier to understand … Through being involved in this project, I have stopped doing this. Students are now working with very sophisticated and demanding texts. They are spending more time looking at the structure of the text and how to approach it. I am now explaining to students how to do this process for themselves instead of doing it for them in advance.

And we saw changes in students’ attitudes: following students’ academic induction day, teachers reported that students asked for more reading and writing in the classroom. Such changed student attitudes and motivation to engage with literacy were critical in enabling teachers to extend their literacy expectations and activities.

Academic literacy lies at the centre of the transition students must negotiate as they move to tertiary study. Further, we contend that a lack of professional, curricula, and pedagogical conversations between the tertiary and secondary sectors continues to generate misinformation and reinforce irrelevant and archaic perspectives and beliefs. Such misinformation, combined with the pressures on teachers, does our students a great disservice.

To start the conversations across sectors, we need to develop a relational framework where teachers in both sectors can build professional connections. Teachers in both sectors need to reinterpret instructional materials through a literacy curriculum lens that makes obvious their implicit academic literacy and information-skills requirements. We need to support teachers’ work with resources that scaffold and support the process of teaching and learning academic literacy and information skills in multidisciplinary contexts. And we need to engage the tertiary sector more fully, to adjust tertiary teachers’ beliefs and assumptions about both literacy and student preparedness, and enable them to take more responsibility for supporting students across the transition. Both sectors need to change—and literacy is at the heart of that change.

References

Bauerlein, M. (2015). What’s the point of a professor? Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/10/opinion/sunday/whats-the-point-of-a-professor.html?_r=1

Cameron, C., & Catt, C. (2013, November). Learning centre practice in Aotearoa/New Zealand: Preliminary report 1. Paper presented at the International Conference of the Association of Tertiary Learning Advisors of Aotearoa/New Zealand (ATLAANZ), Napier. Retrieved from http://researcharchive.wintec.ac.nz/3470/3/ATLAANZ%20Academic%20Journal2014_4Nov_v7.pdf

Gilliver-Brown, K., & Johnson, E. M. (2009, December). Academic literacy development: A multiple perspectives approach to blended learning. Paper presented at the 26th Annual Ascilite International Conference, Auckland. Retrieved from http://www.ascilite.org.au/conferences/auckland09/procs/gilliver-brown.pdf

Kilpin, K., Emerson, L. & Feekery, A. (2014a). Information literacy and the transition to tertiary. English in Aotearoa, 83, 13–19.

Kilpin, K., Emerson, L., & Feekery, A. (2014b). Starting the conversation: Student transition from secondary to academic literacy. Curriculum Matters, 10, 94–114.

Ministry of Education. (2007). The New Zealand curriculum. Wellington: Learning Media.

Ministry of Education. (2013, 29 January). NCEA aligned to the New Zealand curriculum. The New Zealand Education Gazette Tukutuku Kōrero. Retrieved from http://www.edgazette.govt.nz/Articles/Article.aspx?ArticleId=8729

New Zealand Qualifications Authority. (2013, 27 February). Alignment of NCEA level 1 and level 2 versions. Retrieved from http://www.nzqa.govt.nz/about-us/news/alignment-of-ncea-level-1-and-level-2-versions/

Owen, H., & Schwenger, B. (2009). Increasing student success through effective literacy and numeracy support. Retrieved from https://akoaotearoa.ac.nz/community/recommended-resources-ako-aotearoa/resources/books/increasing-student-success-through-effe

Parsons, K. (2015). Message to my freshman students. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/keith-m-parsons/message-to-my-freshman-st_b_7275016.html?ir=World

Radio New Zealand. (2014). Uni to raise English standards [News item]. Retrieved from http://www.radionz.co.nz/news/national/244083/uni-to-raise-ncea-english-standard

Secker, J., & Coonan, E. (2013). Introduction. In J. Secker & E. Coonan (Eds.), Rethinking information literacy: A practical framework for supporting academic literacy (pp. xv–xxx). London: Facet Publishing.

University of Auckland. (n.d.). Academic expectations. Retrieved from https://www.auckland.ac.nz/en/for/international-students/is-life-at-auckland/is-living-in-auckland-and-new-zealand/is-academic-expectations.html#6b927c4d1cbdc167921fdce73f1f8cae

Lisa Emerson is a teacher and researcher in the School of English and Media Studies at Massey University. She was a Fulbright Senior Scholar in 2013, and won the Prime Minister’s Award for Sustained Excellence in Tertiary Teaching in 2008.

Lisa Emerson is a teacher and researcher in the School of English and Media Studies at Massey University. She was a Fulbright Senior Scholar in 2013, and won the Prime Minister’s Award for Sustained Excellence in Tertiary Teaching in 2008.

Email: L.Emerson@massey.ac.nz

Ken Kilpin tutors in English and adolescent literacy at Massey. Ken has extensive experience in the secondary sector

Ken Kilpin tutors in English and adolescent literacy at Massey. Ken has extensive experience in the secondary sector

Dr Angela Feekery is a lecturer in Massey’s School of Communication, Journalism and Marketing. Her research interests include information literacy and understanding how university academics can better support students’ transition into tertiary academic literacy.

Dr Angela Feekery is a lecturer in Massey’s School of Communication, Journalism and Marketing. Her research interests include information literacy and understanding how university academics can better support students’ transition into tertiary academic literacy.