Approaching classroom assessment after the NCEA review

Charles Darr

The New Zealand Government has announced a change package in response to a recent review of the National Certificates of Educational Achievement (NCEA). In this article Charles Darr, a chief researcher at the New Zealand Council for Educational Research, outlines several elements of standards-based assessment that can usefully inform NCEA’s future development, especially in regard to the new standards being shaped. The article also explores how NCEA’s revision might provide an opportunity for teachers to consider their role in ensuring the validity of assessment in their classrooms. To quote from below: “Perhaps the biggest assessment opportunity presented by the change package is the chance to reconsider what is at the heart of our learning programmes and to design approaches to assessment that recognise this.”

Introduction

The recent review of the National Certificates of Educational Achievement (NCEA) has resulted in the Government announcing a “change package”. The package involves seven changes.

1.Make NCEA more accessible.

2.Mana ōrite mō te mātauranga Māori.

3.Strengthen literacy and numeracy requirements.

4.Have fewer, larger standards.

5.Simplify NCEA’s structure.

6.Show clearer pathways to further education and employment.

7.Keep NCEA Level 1 as an optional level. (Education Central, 2019)

The Ministry of Education is now working with stakeholders on the design of these changes and the implications associated with implementing each one.

Change involves disruption, but it also involves opportunity. One opportunity that comes with the change package is the chance to revisit our understandings of the standards-based assessment model that underpins NCEA. Another is the opportunity to reconsider the summative assessment approaches we apply to make NCEA work in the classroom. This article is concerned with both opportunities. The first section considers what standards-based assessment is, including what essential elements need to be in place for it to work. The second section explores how a focus on validity might inform classroom-based assessment post the NCEA review.

1. What is standards-based assessment?

The standards-based approach to assessment is a development of criterion-based testing, which became popular in the United States during the 1970s. Subsequently, it influenced assessment systems all around the world. Central to the idea of a standards-based approach is a commitment to judging achievement against described levels of performance rather than against the achievement of other students. The big idea underpinning the approach is that levels of achievement can be specified in advance and judgements made as to which level best describes how well a student has achieved.

The standard-based approach is very appealing. It is student-centered and focused on transparency. When it is coupled with a belief in authentic approaches to assessment and a trust in the ability of educators to warrant that standards have been met, it is arguably well placed to support a future-focused curriculum that engages a diverse range of students.

New Zealand’s NCEA experience has, at least to some extent, borne out the truth of these assertions. We have seen innovation in local curriculum, an expanded set of pathways for students, and higher rates of participation and success in the senior school. However, there has also been evidence of negative effects. These include reports of over-assessment, the use of coaching and scaffolding to get students “over the line”, inconsistency in the application of standards, a focus on credit-harvesting, the atomisation of knowledge, and negative impacts on the wellbeing of students and educators. At times, there has been a danger of slipping from a focus on “assessment for learning” into what Torrance (2007) calls “assessment as learning”. Here, Torrance is using the term pejoratively to describe a system where learning has become equated with simply completing required assessment activities.

Given this mix of positive and negative impacts, it seems apt to use the opportunity the change package presents to revisit how a standards-based system is meant to work and to think about the lessons we can apply as we move towards a new phase.

It’s harder than it looks

All over the world, proponents of standards-based approaches to assessment have had to admit that implementing them is difficult. At the heart of this dilemma is the realisation that it is virtually impossible to express standards in such a way that their meaning is completely transparent.

As early as the 1990s, Alison Wolf was describing how attempts to write standards in a range of contexts had often resulted in the need to provide more and more definition and supporting documentation (Wolf, 1995). Describing work to define learning domains in order to provide “clear and unambiguous ‘grade criteria’” for General Certificate of Education (GCE) examinations in the United Kingdom, Wolf notes: “Attempts to specify domains led, in every subject group, to the further elaboration of sub domains, sub-sub-domains—and no doubt sub-sub-sub domains too” (p.73).

Sadler (1987) argues that standards based on written descriptions are necessarily “fuzzy”. Words must be interpreted and what they mean is context specific. Finding the correct meaning requires appropriate experience and background knowledge. Sadler, however, is a proponent of standards. Rather than viewing fuzziness as an intractable problem, he suggests that three key elements are needed to support a system based on standards: clear written descriptions, annotated exemplification, and tacit knowledge.

Element 1: Clear written descriptions

The first of Sadler’s (1987) elements is clear written descriptions. (Sadler uses the term verbal descriptions to refer to written descriptions.) These should define the criteria involved in making a judgement and describe the level or levels (standards) required.

Sadler (1987) goes to some lengths to distinguish criteria from standards. He defines criteria as the characteristics or attributes we use to judge the quality of something. For example, “structure” is one criterion among many that could be used to judge the quality of an essay. Essays, overall, can be more or less well structured and we can usually tell when one essay is better structured than another. However, there are no set borders that mark different levels (standards) of structure. Standards, on the other hand, point to the level of achievement we are looking for on a criterion or set of criteria. For example, when we describe that the structure is “clear and concise”, we have attempted to specify the standard we are looking for in terms of structure.

The changes to NCEA involve developing “fewer, larger” standards (Kōrero Mātauranga, 2019). The updated standards will need to describe the actual criteria in play and ensure that descriptions of what it means to achieve at different levels (in the case of achievement standards, Achieved, Merit, and Excellence) are well differentiated.

Sadler (1987) notes that the development of written descriptions involves abstracting criteria and levels on those criteria “from real or hypothetical assessments” (p. 202). This suggests that the writers of the new standards need to have a knowledge of the kind of work students produce, and a well-defined vocabulary to express what is characteristic of different levels of competence in their discipline.

Element 2: Annotated exemplars

Sadler’s (1987) second key element is annotated exemplars that illustrate the different levels of quality. These are examples of students’ work with notes pointing to how students have met the requirements of a standard. As such, they provide “concrete referents” (p. 207) that help users interpret the written descriptions. Sadler makes a special mention of what he calls “threshold exemplars”. These exemplars illustrate achievement at the boundaries between levels (for example, between Merit and Excellence). That is, they are examples of competence that “are considered to be just sufficient to qualify for the standard in question” (p. 207).

In the current NCEA system, some people have been suspicious of exemplification, worrying that it will lead to students blindly recreating the examples they have been given. Instead of exemplification, the focus at a system level has often been on providing educators with common assessment tasks as a way of minimising inconsistencies in judgements. While banks of common tasks can be very useful, they can also be problematic. Harlen (2005) argues that “tightly specifying tasks does not necessarily increase reliability and is likely to reduce validity by reducing the opportunity for a broad range of learning outcomes to be included” (p. 213). Rather than a sole focus on providing common assessment tasks, Harlen (2004) argues for the use of resources to identify detailed criteria (including exemplification), noting: “This will support teachers’ understanding of the learning goals and may make it possible to equate the curriculum with assessment tasks” (p. 7).

Creating the new standards will require making decisions about tasks and exemplars. Both will be needed. It will be important, however, that the tasks and exemplars don’t promote shallow approaches to learning. The focus needs to be on helping educators and students understand the dimensions of quality associated with each new standard so that these are recognised and promoted.

Element 3: Tacit knowledge

Sadler’s final key element for a standards-based system is the tacit knowledge that educators bring to assessing against a standard. He notes that while written descriptions and exemplars can work together to form a strong framework for judgement, they don’t “render superfluous the tacit knowledge of human appraisers” (Sadler, 1987, p. 207). Standards and exemplars are not enough. They ultimately need to be interpreted by knowledgeable people.

This element is a crucial one and indicates that effort must be put into supporting educators to develop shared interpretations. The research indicates that educators working as part of well-maintained professional communities can develop very consistent views of what reaching a standard entails (Wiliam, 1996; Wolf, 1995). Interestingly, this can happen even when the documentation (the written descriptions and exemplars) supporting the standards is sparse or non-existent. In these situations, educators, over time, have had multiple opportunities to view and discuss student work with other educators and have developed a shared understanding of quality.

Moderation processes are one approach to supporting the development of shared interpretation. It is important, however, that they are used strategically to support a shared view of quality within and between schools and other learning organisations. Moderation activities that are not timely, that provide limited amounts of feedback, that are overbearing or punitive, or that focus mainly on the surface features of a performance are less likely to support the development of shared meaning within a professional community.

2. How might a focus on validity inform how we approach classroom assessment?

What opportunity do we have, given the NCEA change package, to improve classroom-based summative assessment in a standards-based environment?

Black, Harrison, Hodgen, Marshall, and Serret (2010) found that a productive starting point for a group of teachers in England who were concerned with improving their classroom-based summative assessment practices was to do a “stocktake” of their assessment activity. Key to this was a strong focus on what it meant to carry out valid assessment.

Revisiting validity

Validity is the most important idea in assessment. Validating an assessment involves determining the extent to which the interpretations and uses of assessment results can be justified. Part of this involves considering the reliability of the assessment process. Would the same results be forthcoming if the process were repeated?

Black et al. (2010) found that once the stocktake was underway, it was useful for the educators to become involved in a debate about what it meant to validly assess their learning area. The question “What does it mean to be good in your subject area?” provided a strong stimulant for critical discussion.

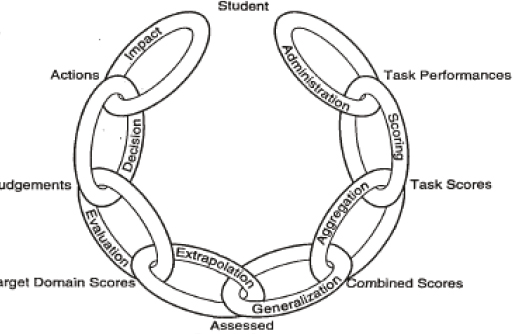

As part of their exploration of validity, the educators considered a model for validation described by Crooks, Kane, and Cohen (1996). In this model, the process of assessment is divided into several stages. Each stage brings different aspects of assessment to the fore, such as the tasks used, how they are administered, the scoring and decision-making processes that are applied, the aggregation process, and the impact the assessment has on students and learning. At each stage, different threats to validity must be considered. Crooks et al. present the stages as links in a chain (see Figure 1). One weak link can jeopardise the whole validity argument, even when other links are robust.

When standards are internally assessed, educators need to make critical decisions about each stage of the assessment process. These include deciding on what counts as evidence, how much evidence is required, what level of support or accommodation is appropriate, and so on. Perhaps the most important need is for educators to have a strong understanding of what they are claiming when they judge a student has reached a standard and the nature of the evidence they consider is sufficient to warrant that claim.

Sadler (2007) describes his view of what it means to learn something this way.

For my money, learners can be said to have learned something when three conditions are satisfied. They must be able to do, on demand, something they could not do before. They have to be able to do it independently of particular others, those others being primarily the teacher and members of a learning group (if any). And they must be able to do it well. (p. 390)

Sadler (2007) emphasises that, in general, we should be concerned that something that has been learned is reproducible. Coaching or scaffolding a student to do something once only leads to a weak validity claim. He writes, “In theory, we are interested in capability, interpreted as the prospect of successful repeat performances in a context of task variance” (p. 391).

Rethinking validity within NCEA

One of the most important parts of validating our classroom assessment approaches within NCEA is to consider the extent to which they support the aims and intentions of the courses we have designed for and with our students.

Cedric Hall (2000), commenting on NCEA before it was implemented, notes: “If standards are to make sense they need to be embedded within a teaching and learning structure which ensures that the objectives, content, delivery and assessment are all connected” (p. 191).

Hall (2000) describes standards as “bricks” that can form the basis for assessing a course of learning. He warns, however, that a fixation with assessing each standard separately will ultimately be detrimental to learning.

The “mortar” for the course, the particular knowledge and skills which connect standards and provide the integration and transfer of knowledge from one point of the course to another, is likely to be de-emphasised or decontextualised in any scheme which treats standards as separate entities (p. 190).

Perhaps the biggest assessment opportunity presented by the change package is the chance to reconsider what is at the heart of our learning programmes and to design approaches to assessment that recognise this. Our programmes should weave together valuable discipline knowledge with key competencies. They should be designed to engage and motivate students, and they should be fun to teach. Our assessment approaches should complement these aims. They (our assessment approaches) should fundamentally be about recognising and encouraging the kind of learning that really matters in ways that support valid claims about what learners know and can do.

Figure 1. Crooks et al.’s (1996) chain-link model for use in the validation and planning of assessments

Final thoughts

The change package for NCEA announced by the New Zealand Government presents an opportunity for everyone involved in the system to reconsider how they are using and supporting assessment and what impacts we want assessment to have on learning. At the school and classroom level, the change presents the opportunity to do a stocktake and reconsider the quality of assessment approaches and the claims regarding learning we need to be able to justify. At a national level, the opportunity involves constructing an appropriate infrastructure for a standards-based approach, including well-expressed and exemplified standards. Such an infrastructure needs to do three things: champion learning and learners, thoroughly support the critical role of educators and their professional communities, and promote assessment for learning rather than assessment as learning.

References

Black, P., Harrison, C., Hodgen, J., Marshall, B., & Serret, N. (2010). Validity in teachers’ summative assessments. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 17(2), 215–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/09695941003696016

Crooks, T. J., Kane, M. T., & Cohen, A. S. (1996). Threats to the valid use of assessments. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 3(3), 265–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594960030302

Education Central. (2019, May 13). Changes to NCEA announced. Retrieved from https://educationcentral.co.nz/changes-to-ncea-announced/

Hall, C. (2000). National Certificate of Educational Achievement: Issues of reliability, validity and manageability. New Zealand Annual Review of Education, 9, 173–196.

Harlen, W. (2004). A systematic review of the evidence of reliability and validity of assessment by teachers used for summative purposes. In Research Evidence in Education Library. London, England: EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education.

Harlen, W. (2005). Teachers’ summative practices and assessment for learning—tensions and synergies. Curriculum Journal, 16(2), 207–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585170500136093

Kōrero Mātauranga. (2019). Have fewer, larger standards. Retrieved from https://conversation.education.govt.nz/conversations/ncea-review/change-package/

Sadler, D. R. (1987). Specifying and promulgating achievement standards. Oxford Review of Education, 13(2), 191–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305498870130207

Sadler, D. R. (2007). Perils in the meticulous specification of goals and assessment criteria. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 14(3), 387–392. https://doi.org/10.1080/09695940701592097

Torrance, H. (2007). Assessment as learning? How the use of explicit learning objectives, assessment criteria and feedback in post‐secondary education and training can come to dominate learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 14(3), 281–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/09695940701591867

Wiliam, D. (1996). Standards in examinations: A matter of trust? Curriculum Journal, 7(3), 293–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/0958517960070303

Wolf, A. (1995). Competence-based assessment. Buckingham, England: Open University Press.