Envisioning a better future through interrelatedness and whanaungatanga

Robyn Zink

Key points

•Explore whanaungatanga and interrelatedness alongside the science of climate change.

•Explore “where we have come from and what we know now” to support student creativity in envisioning their futures and reimagining our current social practices.

•Take the time to envision the future before looking at the problem of climate change.

Climate change is described as the defining issue of our time. There are many climate-change teaching resources that cover the science of climate change and actions to make a difference. However, there is limited focus on envisioning the future we want to create together. Enviroschools’ key concepts of interrelatedness and whanaungatanga support students, schools and communities to explore how they are connected to each other and the world they live in. Using an example from one school, I suggest building understanding of how we are all interconnected is one way to create space to imagine the change we want.

Introduction

“We are the change and change is coming”

(Thunberg, 2019, p. 100).

Climate change is an issue students and teachers are talking about more frequently. This is evident through my work in the Enviroschools programme (Enviroschools, n.d.) as well as the Schools Strike 4 Climate, small actions individual students and teachers are taking, and the collective actions in schools and the wider community. New Zealand youth surveyed in 2019 identified bleak futures and climate change as among the biggest challenges facing young people (Fleming et al., 2020).

Greta Thunberg (2019) said, “We are the change and change is coming” (p. 100). But how well are we equipping ourselves and students to imagine the change we want and to create the pathways and actions needed to bring those changes to life? In this article I describe how Enviroschools aims to weave concepts of whanaungatanga and interrelatedness into our work with schools and how this can create space to imagine the change we want. I give an example of how one school has approached connecting to their place, and the creativity this generated when redesigning their town.

Climate change: The defining issue of our time

As the defining issue of our time, climate change is largely construed as a problem to be solved or a crisis to be managed. Monroe et al. (2019) state that learning about the science of climate change and offering strategies for taking action are common features of most climate-change education programmes. The lack of climate-change knowledge and the misinformation circulating about climate change makes teaching about climate-change challenging. While many teaching resources focus on the science of climate change, Donnelly Hall (2015) reminds us it is increasingly clear that more information about climate change does not lead to behaviour change.

Early in 2020 a group of Dunedin senior secondary-school students attending an Enviroschools hui on leadership were asked to respond to the statement “I want to live in a world where ...” The answers were wide-ranging. From having a good public transport system to “I want to live in a world where people can live together in peace” and “I want to live in world where all people have HOPE”. These statements make an interesting juxtaposition to climate change as a “problem to be solved”. While a peaceful and hopeful future are implied through taking action, not enough is made of the need to “think about what really and profoundly matters, to collectively envision a better future, and then to become practical visionaries in realising that future.” (Kagawa & Selby, cited in Monroe et al., 2019). Niki Harré (2011) argues framing climate change as “the problem” can stymie the creativity and willingness to try things that will enable us to envision and create a better future together.

Connection and relationship

Creating a better future requires much more than the knowledge, skills, and ability to solve problems. It fundamentally requires us to examine our relationships with one another, the places where we live, and the natural environment. Enviroschools’ kaupapa is creating a healthy, peaceful, sustainable world through learning and taking action together (Enviroschools, n.d.). Enviroschools is underpinned by five guiding principles and a series of key concepts. The guiding principle of Māori perspectives and the key concept of “Everything is Connected—Interrelatedness, Whanaungatanga, Whakapapa”, are two elements of Enviroschools that facilitate discussion about what really matters and how we can collectively envision a better future. The guiding principle of Māori perspectives offers insights unique to the culture with the longest history of human interaction with this country. Including Māori perspectives enriches the learning process and honours the indigenous people of this land…Māori understandings of environment…are a doorway to seeing the environment in a cultural light. This will contribute to developing concepts of sustainability that embrace our sense of place, and our unique heritage as a nation (Toimata Foundation, 2020, p.12).

Interrelatedness, or whanaungatanga and whakapapa, is a key concept that helps to bring the guiding principles to life. Whanaungatanga is about relationship, kinship, and family connection. Its long-standing sense is commented on by Mead (2003), who writes: “The whanaungatanga principle reached beyond actual whakapapa relationships and included relationships to non-kin persons who became like kin through shared experiences” (p. 28). Whanaungatanga extends to relationships between people, the physical world and atua or spiritual entities (Bargh, 2019, p. 38).

Whanaungatanga and whakapapa offer ways of understanding our relationships with one another and the world that we live in. They speak to shared experiences, working together, and a sense of belonging. Whanaungatanga and whakapapa bring an added dimension by highlighting that we are connected to all the beings around us through whakapapa. Western sciences also provide a way of understanding the fundamental interconnectedness between life forms and their environments, for example through shared ancestries, and complex ecological relationships and interdependencies.

All cultures and knowledge systems have ways of thinking about and living with one another and in the environment. Katrina Marcel (cited in Trebeck & Williams, 2019) expresses similar ideas from a different cultural perspective when she says; “We could go from trying to own the world to trying to feel at home in it … and that’s when you take off your shoes—prepared to stay a while” (p. 1).

Part of the journey of Enviroschools is to explore the traditions, pathways, and unique wisdoms that different cultures and knowledge systems bring to developing concepts of sustainability and our sense of place.1

Building interrelatedness and whanaungatanga

As Katrina Marcel (cited in Trebeck & Williams, 2019) says, we need to start feeling at home in the world. Taking our shoes off requires us to move more slowly and invites us to literally feel our connection to the earth. It is about taking time, sharing experiences, and creating a sense of belonging—a way into whanaungatanga. So rather than starting with a “problem”, the process Enviroschools use starts by finding out what the current situation is. Even if it is a problem that is igniting interest, the first question is “where have we come from and what do we know now?” The Action Learning Cycle (Toimata Foundation, 2018) is central to the Enviroschools approach to inquiry-based action learning.

Schools are encouraged to explore questions such as, What can we observe and learn? What different cultural and social perspectives are there, and how do others think, act, and feel? What do we want to be able to DO? What special qualities do we want in different places? How do we want the centre or school or community to feel, look, and sound? How do we want to behave toward one another? (Toimata Foundation, 2020). The aim is to create space to enable students, teachers, and the wider community to create shared understandings, to find links between one another, the school and the community, the local environment and larger global issues. Collectively envisioning a better future affects what schools think is worth doing in the present. Building connections and understanding how we are all interconnected is one way to nurture the creativity and willingness to try things to build a future where all can flourish.

Connect to My Place, Make a Difference in My Space

Schools are engaging with these processes in a myriad of ways, ranging in scale from the classroom to the whole school connecting with the wider community. One recent example comes from an Otago primary school engaged in a year-long, whole-school inquiry, Connect to My Place, Make a Difference in My Space. Students explored an array of aspects of their school and community. Each class spent time imagining their visions of a healthy sustainable school and world. One class became interested in the consultation process which the local council was running at the time for the redevelopment of the waterfront area in town. The waterfront has some green space but is also the largest carpark for the downtown area. The students brainstormed what they wanted to be able to do at the waterfront and how it could feel, look, and sound. They already knew they wanted places to play and hang out with their friends and families and they wanted to see areas with lots of native plants providing homes and food for birds and insects. They wanted to see artworks in the area that reflected the different cultures in their community, like the work they had created in their classrooms.

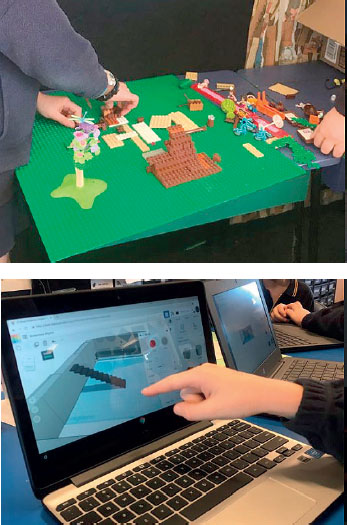

The students started to work on a “new” waterfront area but, when they were challenged to think about what would need to be included in a sustainable waterfront that would be good both for people and for the environment, they realised that it did not need to include cars. The teacher working with the students said it was like someone had pulled out the stopper on their creativity once the students realised that cars didn’t need to take priority. The students did not stop at redesigning the waterfront. They started to redesign the whole town so that it would be a place that is good for people and the environment. The students knew people still needed to move around town which led to them finding out about the ways people travel now. Where did they go in a car and what are the alternatives? Where could they bike or walk and what could public transport look like in their town where there is currently none? What did people with limited mobility need to access the waterfront area and town? The students went on to build models of their vision of the waterfront to share with the council and the community.

FIGURE 1. STUDENTS BUILT MODELS OF THEIR VISION OF THE WATERFRONT TO SHARE WITH COUNCIL AND THE COMMUNITY. SOME CHOSE TO BUILD A PHYSICAL MODEL AND OTHERS UTILISED DIGITAL TECHNOLOGY TO CREATE THEIR MODEL.

Enviroschools’ bicultural approach

Enviroschools was developed by a group with diverse backgrounds including Te Mauri Tau, a kaupapa Māori educational, environmental, and health organisation based in Whaingaroa/Raglan. Through this core partnership came the development of the first Enviroschools Kit and facilitator training programme underpinned by five guiding principles, including the principle of Māori perspectives. The Enviroschools Kit and facilitator training programme acknowledge the richness and complexity of weaving Māori perspectives, and the many challenges of including Māori perspectives in a written resource in an English-medium learning context.

In deciding to include Māori knowledge in this Kit, we have drawn upon some previously published material. We have also created some activities to make links to the particular issues Enviroschools explores. This can be challenging for many reasons. First, because the Kit is in English. Secondly, because the Kit has been written as a national resource, but the right way to do things Māori is to observe and honour what is local. Thirdly, because this is a written resource while Māori is based on oral transmission of knowledge. And finally, because Māori culture has been so affected by the colonial experience. Though the culture was intact before colonisation, the changes which followed it were sufficient to splinter it and to scatter many of the fragments. While picking up the pieces, it would seem that nobody anywhere has picked up the same pieces. What we offer here are some of the parts we have been able to gather, that best convey the Enviroschools kaupapa. (Toimata Foundation, 2018, p. 5)

Enviroschools does not offer answers, but rather guidance for participants to travel on their own learning pathway, and participants are asked to always seek out “in a sensitive way, the stories, language, and knowledge that are a part of the land where they are and held by the tangata whenua of their place.” (Toimata Foundation, 2018, p. 5). Toimata Foundation, which grew out of the Enviroschools Foundation and continues to work in partnership with Te Mauri Tau, now supports Enviroschools and Te Aho Tū Roa. Te Aho Tū Roa is a programme in te reo Māori working with kōhanga/puna reo, kura, wharekura, and communities that embrace Māori culture, language, and wisdom.

Within Enviroschools we have robust discussions about how to honour and integrate the depth and complexity of Māori perspectives in our work and how Western concepts of sustainability connect or contrast with Māori perspectives and what this means for our practice.

The students were able to generate a lot of ideas because they had spent time finding out about their place and exploring their relationships and interconnections with the people, plants, and animals they share their place with. This gave them the tools and confidence to imagine the change they wanted and do it in such a way as to enhance the natural world and their community. Climate change was part of the discussion as the students worked through their visions and plans, but it was not the primary problem they were trying to solve. The students set out to create a space that would be better for people and the environment. Their explorations and visions were framed by how things are interconnected rather than as a response to the problem of climate change. The solutions they proposed did address climate change as they reimagined how people would get around and what they would do, not because they set out to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but because they wanted a more connected community that is good for people and the environment.

Conclusion

Climate change is the defining issue of our time, and understanding the scientific processes that drive climate change is important, as is taking action to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions. But climate change is symptomatic of, and a result of, our current social practices of trying to “own the world” rather than being at home in it. It is symptomatic of the break-down in our relationships with others and the world around us. As Harré (2018) suggests, change is about “helping to create a viable alternative to our current social practices” (p. 9). The way we endeavour to do this at Enviroschools is by learning and taking action together. Through shared experience, working together, and providing people with a sense of belonging we hope that people recognise and deepen their connections to others, including the environment.

If we really do want to create a world where we can live together in peace, where all people have hope, then we do need to find new ways of working together. As Greta Thunberg said, change is coming, so let’s be the change that “contributes to the on-going task of all human communities: to figure out how to nurture each other and the planet we inhabit” (Harré, 2018, p. 209). In Otago Enviroschools we are feeling our way into this space in our work with schools and communities. At times we stumble and misstep, but we hope that we are working toward creating spaces where creativity and willingness to try things can flourish by keeping our interrelatedness and whanaungatanga to the fore in everything we do.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Heidi Mardon (Toimata Foundation) and Esther Kirk (Enviroschools) for their support and input in writing this article. A particular thanks to the students, teachers, and Enviroschools facilitators I work with through Enviroschools. They inspire me with their motivation and enthusiasm and challenge me to keep examining my assumptions and understanding of how the world works.

Note

References

Bargh, M. (2019). A tika transition. In D. Hall (Ed.), A careful revolution towards a low-emissions future (pp. 36–51). Bridget Williams Books. https://doi.org/10.7810/9781988545684_2

Donnelly Hall, S. (2015). Learning to imagine the future: The value of affirmative speculation in climate change education. Resilience: A Journal of the Environmental Humanities, 2(2), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.5250/resilience.2.2.004

Enviroschools (n.d). Enviroschools. https://enviroschools.org.nz/

Fleming, T., Ball, J., Kang, K., Sutcliffe, K., Lambert, M., Peiris-John, R., & Clark, T. (2020). Youth19: Youth Voice Brief. Retrieved from The Youth19 Research Group, Wellington: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5bdbb75ccef37259122e59aa/t/5f3394a2654885030c051243/1597215912482/Youth19+Youth+Voice+Brief.pdf

Harré, N. (2011). Psychology for a better world: Working with people to save the planet. Auckland University Press.

Harré, N. (2018). The infinite game: How to live well together. Auckland University Press.

Mead, H.M. (2003). Tikanga Māori: Living by Māori values. Huia.

Monroe, M.C., Plate R., Oxarart A., Bowers A. & Chaves W. A., (2019) Identifying effective climate change education strategies: A systematic review of the research. Environmental Education Research, 25(6), 791–812. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2017.1360842

Thunberg, G. (2019). No one is too small to make a difference. Penguin Random House.

Toimata Foundation. (2018). Enviroschools kit. Author.

Toimata Foundation. (2020). Enviroschools handbook. Author.

Trebeck K., & Williams, J. (2019). The economics of arrival: Ideas for a grown up economy. Policy Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvb1hrn9

Robyn Zink joined Enviroschools as Otago Regional Coordinator 4 years ago. Before this she worked as an outdoor and environmental educator, and has undertaken numerous research projects with a focus on young people’s experiences of learning in outdoor environments.

Robyn Zink joined Enviroschools as Otago Regional Coordinator 4 years ago. Before this she worked as an outdoor and environmental educator, and has undertaken numerous research projects with a focus on young people’s experiences of learning in outdoor environments.

Email: robyn.zink@orc.govt.nz