EMPOWERING STUDENTS TO BECOME SELF-REGULATING WRITERS:

THE JOURNEY OF ONE CLASS

Verena Watson

This article follows a study that identified the strategies one teacher used to support the development of self-regulating writing behaviours for her Year 5 and 6 students. A researcher from the New Zealand Council for Educational Research worked alongside the teacher in planning a 5-week sequence of lessons focusing on persuasive writing. As the teacher and students worked through this programme, two researchers made observations of and interviewed six students in this class—three girls and three boys (the study group). These students represented a range of abilities across levels 2 and 3 of the English curriculum. Their responses to the strategies and to the programme are also identified in this article.

An overview of the journey

To begin the journey, the teacher engaged in deliberate acts of teaching to support the students both in their writing and in the self-regulation of their learning. En route, strategies and skills for both persuasive writing and self-regulated learning were modelled and scaffolded. These practices were reinforced through the provision of support materials and via student–teacher and student–student conferences, fostering a class that saw itself as a learning community. This article explains the evidence that was gathered of all these supports and of the developing self-regulating writing behaviours and their benefits that were seen as the students set, worked, and reflected on their learning goals.

Modelling and scaffolding

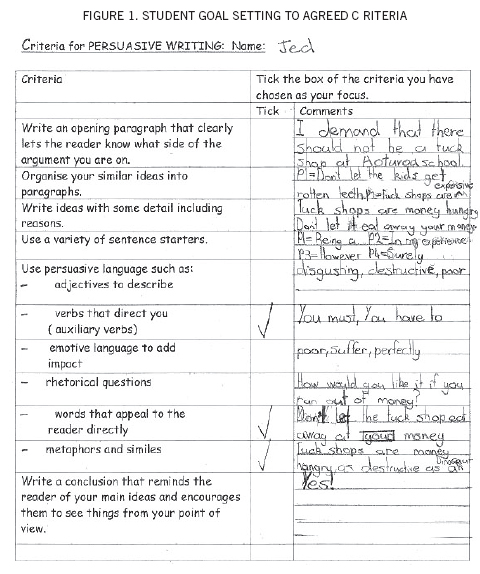

The modelling and exploration of persuasive texts, combined with explicit teaching, formed the foundation for the journey that lay ahead. To begin, the teacher presented a variety of models of persuasive writing. The purpose and the probable audiences of these texts were established. (This was essential, as the purpose drove the evaluations and rewriting of the students’ own writing later in the programme.) As these models were “unpacked” with the students, both the structural and the language features common to these persuasive texts were identified. This work was done within groups and as a whole class, so that everyone shared a common idea of what persuasive texts could look and sound like. This led to the development of success criteria, which the students could use later to guide their own writing when it became a class list of criteria (see Figure 1).

Before the students began trying out each feature, the teacher modelled feature writing for them. The students found supporting evidence in the teacher’s text of the criteria they had compiled as a class and gave feedback, saying how well their criteria had been met. Students then had opportunities to explore the language features further by writing examples in co-operative groups and to evaluate their examples against their criteria. This process gave the students practice in the skills and strategies that would support their abilities to write persuasive texts and to be self-regulating learners. As the teacher explained:

A lot of sharing is what they need; a lot of modelling is what they need. [They need to be] almost saturated in that type of text if you want them to do it. A lot of support as to what a verb might look like, a lot of support as to what an adjective might look like, support of similes and metaphors…working co-operatively so no one child feels threatened. [They need] lots of practice, working co-operatively and with mixed abilities.

When the student scame to embark on their own first full pieces of persuasive writing, the teacher provided a further scaffold by modelling how to brainstorm ideas on a topic using the Positive, Minus, Interesting (PMI) model (a lateral and creative thinking strategy developed by Edward de Bono, 1992). Following this modelling session, the students decided which positions they would take on an argument and completed their own PMIs based on those positions. Students used their PMIs to plan their arguments, with each paragraph having one main idea, supported by evidence.

When writing their first piece, each student used the persuasive writing criteria that were established by the class during the modelling sessions to identify the particular criteria they wished to set as their own learning goals. They wrote one paragraph at a time, then met with a partner to discuss their work and share possible improvements, always referring to their criteria. In evaluating their work, students wrote supporting evidence from their writing beside the goals they were focusing on. An example is shown in Figure 1.

From the final analysis of their first piece of persuasive writing using their criteria, they were able to set the learning goals for their second piece of persuasive writing, thus supporting what they saw as their “next step”.

I looked at my work and only saw adjectives in my first paragraph. So that’s how I decided on my goal. (Student)

The modelling sessions had helped the students understand that the desired outcome of persuasive writing was to write strong arguments, appealing to their readers, “leaving the reader in no doubt as to what you mean and what you think” (Teacher). Students were able to identify the impact that language features could have on readers (audiences):

I didn’t know what they [rhetorical questions] were until yesterday. I just got stuck into them. They can add impact to your argument, like talk directly to the reader.

This is an example of the “unpacking” that occurred in the modelling sessions, which led to the teacher and students together developing explanations and examples of persuasive writing features that they called “class lists”. These were presented as wall charts, so that the class could readily refer to them, and focused on emotive words, words that appeal directly to the reader, auxiliary verbs, sentence starters, metaphors, and similes. These lists were added to throughout the study as new examples of language features were discovered. Students were aware of the links between the support materials available to them and acknowledged the potential of those materials for their future writing:

I did meet my learning goal to use more emotive language, but I got stuck on one idea. Next time I’ll have to think up more ideas to improve my argument. I’ll look at the class lists.

The provision of class support materials alongside teacher modelling and scaffolding contributed to a shift in classroom roles. The students were becoming increasingly more able to monitor and direct their own work—to be self-regulating learners—while the teacher was able to take a step back.

Shifting responsibility through feedback

By the time students had work ready for student–teacher conferencing, a shift of responsibility from teacher to learner had occurred, to the extent that the teacher was able to give feedback with the assumption that students had ownership of their writing. The teacher showed herself to be an interested reader of their persuasive texts, using clear feedback to identify and reinforce students’ self-regulated learning and ownership of their work.

This was evident from the outset at student– teacher conferences, when students started the conferences by reading their work to the teacher and came well prepared, having identified supporting evidence in their texts of having achieved their learning goals. An example demonstrating this shift of responsibility was shown when a student articulated to the teacher that he had focused on the use of similes. He then went on to identify the simile he’d used in his text (“Lollies are as destructive as giant meteorites”), which he’d written against his goal. The teacher affirmed his learning goal and his choice of language when she said, “That really gave me a picture.” The student had not thought of his simile as evoking an image, and together they laughed about the picture that formed in their minds. The specificity of the oral feedback to the student’s learning goal and to his ownership of his work was reinforced in the written feedback that the teacher gave this student the next day:

Your goal was to use similes in your writing. You have done this. I particularly enjoyed reading the simile referring to [a] giant meteorite. I immediately thought of large craters in teeth. (Not a good feeling.) So this added impact to your argument. It appealed to my emotions and how I feel about dentists.

Another way the feedback reflected this shift in roles was the way in which the teacher responded as the reader (or audience) of persuasive texts, rather than as a “teacher-expert”. Her approach here also reinforced the established purpose of persuasive writing:

You met your goals well by appealing to the reader…. [When you read it to me] I listened and I wanted to listen…. You have used many words that appeal directly to the reader such as “you”, “your” and “our”. This makes the reader feel that you are talking to them personally. This helps to give weight to your argument.

While in the role of being an audience for students’ texts, the teacher was able to enter into debate with students, questioning them about alternative solutions, the causes and effects of actions, and the consequences of stances taken. Students had to explain themselves fully, adding details, clarifying their main ideas, or going back to their planning to check that they had included all the ideas they had intended to.

At times, the nature of feedback moved from being about the writing to assisting the students with useful strategies and skills to enhance their self-regulating behaviours. For example, when students needed to add more details to their writing, the teacher advised students to use symbols to show where a new piece of text was to be inserted. She also took care to affirm their self-regulating behaviours:

I liked how you referred to your planning and included a new idea from that.

You have been wearing your green hat when you raised this, and your red hat when you showed your feelings.

Giving students affirmations of their learning built student efficacy and an understanding of its benefits. As one student wrote to the teacher:

I really liked the way you kept on encouraging me even when I was not doing well.

The importance of students having a role in assessing their own work follows from recognising that they are the ones who do the learning and have to make the effort to link experience and ideas in seeking to understand. As Harlen (1998) observes, the teacher’s role is not diminished by identifying the student as the locus of learning but is changed to a role of facilitating students in understanding what they are to learn and in helping them to learn it.

Fostering a learning community

An essential item for a journey towards a self-regulated learning environment is a climate where the benefits of collaboration are understood and valued. In this class, there was an expectation that students would work together co-operatively and productively, sharing ideas, writing tasks, and giving each other constructive feedback. The teacher modelled this with the class, with both groups and individuals, validating their contributions.

[I do this so that] they have a chance to learn from each other, and it’s not teacher directed all the time. (Teacher)

Students appreciated the opportunities that such a class climate offered them:

I talked to my friend. He helped me understand what this means.

I talked with [my friend] after I had analysed my other piece of writing and we both have the same learning goals and we helped each other to see how we could use the lists on the board to help us.

Through the class and group sharing of ideas and strategies, students had a greater pool of ideas and knowledge from which to select. Here again, students were able to articulate the benefits:

P for plus, M for minus and I for interesting—we do this sometimes to share our ideas about a topic. It helps you get more ideas and you can share ideas, thoughts you have.

When monitoring and analysing their work, students demonstrated the ability to be reflective, adaptive, and collaborative workers and learners:

I explained my goal to my buddy and then read my argument to her. Then we talked about it. She said I hadn’t really used any auxiliary verbs, so I went and looked at the chart and found some words I could add to my argument. Then I read it to my buddy again, and she said, “Yeah,” I had now.

Developing reflective learners

By helping students to take responsibility for their work, both individually and collaboratively, the teacher was helping them to become more reflective and critical learners. Self-reflection provides both teachers and students with information that can be used by to modify their work and make it more effective. Honesty from all participants is essential.

I had to think more than usual: about what I’m writing, how I’m writing. (Student)

Look what [the teacher] has written. Look, she’s right. I haven’t used any words that appeal to the reader. I guess I had better go back and add some. (Student)

As the students were writing, the researchers observed all six children writing a bit, rereading their writing, referring to their goals, and reworking. They were self-regulating against identified learning goals:

When I analysed my writing I found lots of things that I should work on, but I want to try hard to get my ideas in a better order and to write more things to support each reason. I need more detail so that people understand what my opinion really is. Oh, I also want to use more emotive language to make my reader feel more. I will keep checking to make sure I remember to work on my learning goals.

Students in this study developed reflective and critical strategies that suited their particular learning styles. Some checked their writing out with each other, often reading aloud passages of their work and asking if they thought their learning goal was being met. One student described how he kept his learning goal in his mind as he wrote, and as he did so he imagined he was talking to someone face to face, checking his work out.

The students’ comments echo findings from other research (Harlen, 1998) that demonstrates the important role students have in assessing their own work, recognising that they are the ones who do the learning.

Empowering students

Taking more responsibility for their learning appeared to empower the students. By setting their own learning goals and specifically stating the strategies that would help them meet the desired criteria, all six students expressed a commitment to their learning, a strengthened self-efficacy, and a motivation to achieve:

I enjoyed this writing because I was in charge. I knew I could achieve my goal. I knew what I could do and what to do to get help.

I like doing my own work and like to do as much as I can do myself.

I like picking my own learning goal because you know what you need.

These findings are consistent with other research showing that successful learning occurs when learners have ownership of their learning, understand the goals they are aiming for, are motivated, and have the skills to achieve success. These elements foster self-efficacy, which in turn enhances student achievement and their level of self-regulation (Schunk, 1991; Zimmerman, Bandura, & Martinez-Pons, 1992.) As Zimmerman explains (1986), it is the development of this capacity to self-regulate that enhances students’ perceptions of themselves as learners.

Challenges in moving forward

The researchers identified challenges for both teacher and students during this study. A shift in responsibility meant that the ability to work in a more self-regulating environment was not necessarily linked to past performance.

The teacher in this study had observed that one of the less able students had managed his own learning well, monitoring his progress and employing strategies to help him achieve his goals, while one of the higher achieving students had struggled, requiring more assistance than her usually less able peers:

I thought this student might struggle as he often has difficulty generating ideas and staying on task with writing activities. Yet I would say he has been the more successful writer. He stayed focused on his goal and it is the first time I have known him to add to his writing to improve the impact on the reader. I wonder what exactly has sparked that change? Maybe the style of teaching before the independent task.

One of the challenges for students is to set goals that are specific and achievable. The higher achieving student referred to above chose all of the criteria compiled by the class, rather than focusing on only a few. This impacted on her motivation as she found she had too many goals to focus on.

Another challenge for students is to see how the skills and strategies acquired in one learning domain transfer into other learning areas and even into their journeys outside of school. One student in the study group made this leap:

I’m going to set myself a goal to get my soccer gear ready the night before. Then I’d be ready on time when Mum wants to leave and we wouldn’t get fighting.

To help students meet this challenge, teachers face their own challenge of making links between learning domains explicit for students and meaningfully incorporating various skills and strategies across curriculum areas. The teacher in this study, for example, said she intended to employ persuasive writing in a later topic study and so was ensuring that her students had skills that they could transfer to that work. Knowing that the success of a later unit of work was dependent on the success of her current focus meant that the teacher had to be able to move between roles, recognising the teachable moment, when to be an expert, and when to give greater control to students in a meaningful way.

Managing a self-regulating classroom is demanding. In this study, as the students were beginning to work more independently, the teacher identified the diverse range of abilities and needs in the class that were becoming apparent and what that meant she would have to do:

There will be children who just understand it one hundred percent and run with it. There are those that need it modelled again and again and again. So you’ve got a management strategy of extending those ones, revisiting with these ones, and then there will be the one that you almost need to do it for them…perhaps choosing from one or two (criteria) that they need to work on, narrow the field down…. The range of abilities in a class is a challenge, but it can be met, making sure that your children who are running with this programme have the opportunity to keep running, broadening their knowledge base, making sure you give enough time to those who need to meet a simpler goal…just trying to arrange strategies, until you get one that works. Sometimes you feel you’re not making progress, until you take time out, and look back on where you’ve come and realise you have travelled down a path. You do move and they do move.

Conclusion

Explicit teaching and modelling of the necessary skills and strategies was vital to the six study students’ development of self-regulating writing behaviours. The teacher provided opportunities for the students to practise both their writing skills and their self-regulating learning behaviours in manageable “bites”. Feedback was specific to the learning goals students had set, the effect of which was to reinforce to the students that they were responsible for driving their learning. This shift in responsibility to the students meant that there was a corresponding shift in the role of the teacher, from that of a teacher expert to that of the audience for the students’ persuasive texts.

The powerful and timely combination of deliberate acts of teaching, support materials, and structures, as well as the explicit feedback specific to learning goals, promoted student ownership and a collaborative and reflective environment and led to the students developing self-regulating writing and learning behaviours.

Acknowledgement

The study was led by NZCER researcher Linda Sinclair.

References

de Bono, E. (1992). Serious creativity: Using the power of lateral thinking to create new ideas. New York: HarperBusiness.

Harlen, W. (1998, December). Classroom assessment: A dimension of purposes and procedures. Paper presented at NZARE conference, Dunedin.

Schunk, D. (1991). Self-efficacy and academic motivation. Educational Psychologist, 26, 233–262.

Zimmerman, B. (1986). Becoming a self-regulated learner: Which are the key subprocesses? Contemporary Educational Psychology, 11, 307–313.

Zimmerman, B., Bandura, A., & Martinez-Pons, M. (1992). Self-motivation for academic attainment: The role of self-efficacy beliefs and personal goal setting. American Educational Research Journal, 29, 663–676.

Notes

As a result of this study, new English resources for the Assessment Resource Banks were developed. The important features of these resources are as follows:

•&&&&They model possible learning intentions.

•&&&&They can be adapted to meet students’ needs by selecting the appropriate learning intentions.

•&&&&By being adaptable, they model the fact that language features are not fixed to particular text forms, but are dependent on other factors, such as audience, purpose, and context. They are for formative and self- and peer-assessment purposes and can be accessed by entering the keywords learning intentions in the English Bank (www.nzcer.org.nz/arb).

Verena Watson is a resource developer for the Assessment Resource Banks and researcher at the New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Email: verena.watson@nzcer.org.nz