How students interpret poetry:

findings from Assessment Resource Banks trials

Sue McDowall and Verena Watson

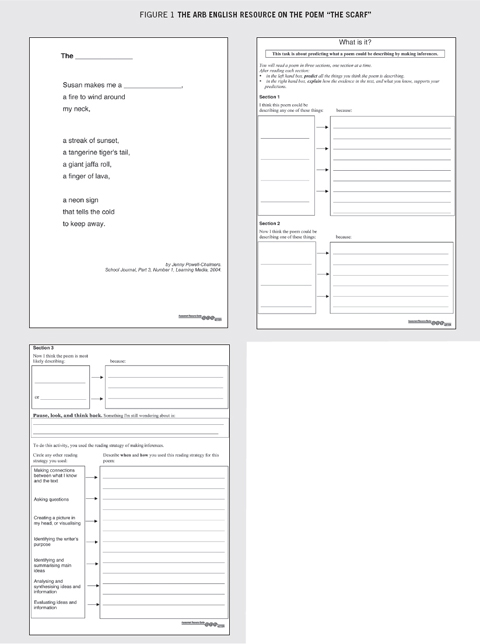

In 2005 the team of writers developing English resources for the Assessment Resource Banks (ARBs) constructed a series of poetry resources designed to assess students’ reading comprehension. We selected poems that described either a concrete or an abstract noun. We obscured the subject of each poem by removing the title and in some cases a word from the body of the text. We then gave students the challenge of working out what the poem was describing by using evidence from the text (one of these test resources is shown in Figure 1). The poems were disclosed progressively, in three or four stages.1 At each stage students were asked to consider what the poem might be describing and to provide evidence supporting their suggestions.

We developed at least one resource to align with each of levels 2, 3, 4, and 5 of English in the New Zealand Curriculum (Ministry of Education, 1994). The requirements of the task remained the same throughout, but texts became increasingly complex, to correspond with increasing curriculum levels. A number of factors contributed to the complexity of these texts, including vocabulary, the use of figurative language, and the subject of the poems. The poems used at the earlier levels tended to describe concrete nouns such as a jandal, while those chosen for the later levels included poems describing abstract nouns such as anger.

We trialled each assessment resource with small groups of students and then with a randomly selected sample of approximately 200 students from Years 4 to 10, as appropriate. In these larger trials we asked classroom teachers to briefly introduce the activity and to take responsibility for the progressive disclosure of the poems, which were provided as overhead projector transparencies. We asked these teachers to explain to students that there was no single “right” answer and that their task was to provide evidence from the poem to support their interpretations. Further details about how to administer the tasks can be found in the Teacher Information section for each of these ARB resources at www.nzcer.org.nz/arb.

In this article we discuss the findings drawn from the trials as they relate to the comprehension strategies used by students across a range of class levels, crossing primary, intermediate, and secondary schools. In particular, we focus on the main factors that affected the ability of students at all levels to comprehend text. These included students’ ability to:

•&&identify the evidence in a text that informed their predictions and interpretations;

•&&alter predictions and interpretations in the light of new evidence;

•&&synthesise evidence drawn from different parts of a text;

•&&understand the vocabulary in the context in which it is used;

•&&interpret figurative language; and

•&&engage with the text and task.

We discuss each of these aspects in greater depth, and highlight the implications of these findings.

We also collected information about students’ metacognition by asking them to describe the comprehension strategies they thought they had used to carry out the assessment task. We did this by asking them to identify, from a list of comprehension strategies drawn from Effective Literacy Practice in Years 1 to 4 (Ministry of Education, 2003) and Effective Literacy Practice in Years 5 to 8 (Ministry of Education, 2006), the strategies they had used, and the points during the task at which they had used them. In this article we make reference to some student responses to this component of the task, but do not present a systematic analysis of student responses across all the resources.

Use of evidence

Ability to identify evidence to support initial interpretations and predictions

The findings of the trial data show that when the first stanza or section of a poem was disclosed, most students across all school levels could make plausible suggestions about what the poem might be describing and provide evidence from the text to support their suggestions.

There was, however, a tendency for students across all levels to provide only one piece of evidence from the text to support their prediction, rather than using all the available evidence. One example of this comes from the responses of Year 9 students to the first section of a poem (Powell-Chalmers, 2004, p. 15) describing a scarf:

Susan makes me a _________,

a fire to wind around

my neck

Most of the Year 9 students in the trial made predictions based on the evidence that the noun being described was something that went around the neck, such as a necklace, tie, or scarf, referring to the evidence “to wind around/my neck”. Fewer students (just over one half) combined this with the additional clue provided in the words “a fire”, which might signal the colour or warmth provided by the noun being described. And only a few students referred to the evidence that the object was something that could be made, as signalled in the words “Susan makes”.

Ability to alter interpretations and predictions in the light of new evidence

This tendency to make predictions based on only one piece of evidence within a stanza or section occurred to an even greater degree across stanzas or sections. For example, after reading each section in a poem describing taps (Dunstan, 1986, p. 30), most of the Year 4 students in the trial made predictions consistent with the evidence provided within the section they had just read, but few demonstrated the ability to combine the evidence built up cumulatively across sections to refine their predictions. For instance, just under half of the students used the evidence in section two of the poem:

Although I try

with all my might

I cannot

tell the left from right

to predict things that have a left and right side, such as shoes or hands. And almost one half of the students used the evidence from section three:

and which

is hot

and which

is cold.

to predict things that could be different temperatures, such as a heater. But less than one fifth used the new evidence to alter their original prediction.

This also occurred with older students. One example comes from the responses of a group of Years 9 and 10 students to a poem describing anger (Miller, 2003, p. 17):

Section one:

______________ is like nicotine,

something you get addicted to.

Section two:

It is bright, electric yellow

and blinds you.

It happens when you push back.

Section three:

You both fall,

go spinning out of control,

until you sit on the ground

covered in bruises,

surprised at the damage you’ve done.

The first section describes the subject of the poem as being “like nicotine/something you get addicted to”. After reading this section, nearly all students made predictions consistent with this evidence. On reading the second section, over half of the students made new predictions that were consistent with some or all of the new evidence in the second section. However, less than one fifth made predictions that were also consistent with the evidence from the first section—“something you get addicted to”.

A possible explanation for this failure to draw on all the evidence available within a text to make predictions, and to alter predictions in the light of new evidence, might be the students’ inability to come up with a suggestion that was consistent with all the evidence provided. In other words, some students may have realised that their prediction was not consistent with all the evidence in the poem, but may have been unable to think of a better possible answer. Given the complexity of some of the poems, particularly those at the later levels, this would be understandable.

However, student responses to the prompt we provided at the end of the task (to “pause, think, and look back” and to complete the sentence “Something I am still wondering about is …”) suggest that a disturbingly large proportion of students whose final prediction was inconsistent with some of the evidence provided in the text did not appear to be aware of this, or did not think it mattered enough to record it. For example, after responding to the poem describing anger, most of the Years 9 and 10 students in the trial made final predictions that were consistent with some but not all of the evidence in the poem. Less than one third of these students commented on their inconsistencies:

Love is not yellow. Red is the colour that goes with love. You cannot push it back, but it can make you blind. (Year 10 student)

If it’s a merry go round, it doesn’t exactly blind you when you push it back. (Year 9 student)

The failure of the students in our trials to check predictions against the evidence available in a text is consistent with the findings of Lai et al. (2004), who hypothesised that high rates of predicting but not checking were a key factor in the relatively low Progressive Achievement Test (PAT) and Supplementary Test of Achievement in Reading (STAR) comprehension scores of many students in their Mangere cluster of schools. Their analysis of test results suggested that student performance was unlikely to stem from widespread decoding problems, but rather from low student rates of checking answers against evidence in the text. This was consistent with their classroom observation data, which revealed that while students frequently engaged in making predictions about text in classroom reading activities, they rarely checked (or were prompted to check) their predictions against evidence in the text.

The inability of the students in our trials to draw together all the evidence in a text and to address any discrepancies between predictions and evidence is consistent with the findings of Greaney (2004). In a retrospective analysis of the PAT Reading Comprehension responses of 31 Years 4–6 students who performed poorly on this test despite being reasonably competent decoders, Greaney found that one of the most common sources of difficulty for students’ comprehension was linking main ideas together.

These findings highlight the need for teachers to focus on the importance of using all the evidence available in texts when making predictions, and to teach students strategies for revising predictions in the light of new evidence.

Use of syntactic evidence

Students’ ability to make accurate predictions was related to their ability to use both semantic and syntactic cues. Their failure to take notice of syntactic cues was demonstrated most noticeably with the poem “If I Were a Storm” (Boom, 2003, p. 18), which was trialled with a group of Year 7 students. The fact that the subject of the poem had to be in the singular is signalled clearly by the syntax of the first two sections of the poem:

Section one:

If I were a ________________,

I would range over farms, plains,

houses, cities, and seas.

Section two:

I would beat against the window panes

of houses

with warm fires inside.

I would whip the leaves off trees.

I would flood rivers while I could.

Section three:

for all too soon, the sun will peep out

from behind a cloud

and I must pick up my black billowing

skirts and leave

to whine over the oceans and beyond.

Despite this, more than one fifth of students made predictions in the plural after reading the first two sections. Responses drawn from this and other resources demonstrate the importance of reading closely the syntax as well as the semantics of text. In the case of this particular poem, the ability to comprehend depended partly on a tiny but very important word: “a”. Our analysis of student responses to this and other resources demonstrated the advantage gained by students who are attentive to syntactic cues for comprehending text. Some examples are provided below. We added the italics for emphasis.

[Something I am still wondering about is] whether it is a cloud because you can’t be a rain but you can be a cloud. (Year 7 student)

[I think it is most likely about] one jandal [because] it says “Have you seen my other”. (Year 4 student)

It doesn’t make sense. Why does it change from you to her? (Year 10 student)

[Now I think it could be about] a watch [or] a hat [or] a toy because they called it it—because it must not be alive. (Year 4 student)

Vocabulary

Greaney (2004) found that only a small number (2.3 percent) of PAT reading comprehension errors made by the students in his study appeared to result from a lack of vocabulary knowledge. We were not able to systematically gather evidence on the extent to which student vocabulary interfered with comprehension, but the process of marking student responses highlighted some common difficulties.

Sometimes these difficulties were caused by new vocabulary. For example, in response to the prompt “Something I’m still wondering about is …” one Year 10 student wrote: “It has words I don’t get in it so it’s hard to say [what the poem is about].”

The use of vocabulary in te reo Māori in a poem describing a greenstone pendant challenged some students.

More common, however, were difficulties caused by vocabulary used in unfamiliar contexts, in terms of either semantics or syntax. We found a number of examples of the incorrect interpretation of homonyms and homophones in students’ responses to the poem that described a storm. One student interpreted the word “plains” (from the line “I would range over farms, plains”) as “planes” and so concluded on reading the first section that the poem was describing an angel, because “an angel can fly higher than plains”. Another student read the word “range” as a noun rather than a verb, and so concluded that the poem was describing a mountain, because “the writer uses the word ‘range’ and you call mountains ranges sometimes”. The word “whine” in the final section of this poem caused similar difficulties. One of the students interpreted this word as “wine” and combined this interpretation with other evidence from the poem to conclude that it was describing a ship, because “on a cruise ship you can be on the ocean and drink wine”.

These types of difficulties occurred in the other poems as well. For example, the poem that describes a greenstone pendant (King-Wall, 1999, p. 23) begins:

Awhi

A spirit released

To accept the receiver

One of the students used prior knowledge of the word “receiver” to conclude on reading the first section that the poem was describing something to do with TV and radio communication.

The vocabulary difficulties students faced did not necessarily prevent them from working out what the poem was describing, particularly if they were able to accommodate new evidence that did not support their initial conclusions, and rethink their original ideas. An example is the student just described, who on reading all sections of the poem revised his initial prediction and at the end reflected, “How wrong I was at the start.”

Interpreting figurative language

Some students’ comprehension was also hindered by their ability to interpret figurative language such as metaphors or similes. This was most apparent with a particularly dense poem given to Year 10 students describing a ladybird (Dodat, 1987, p. 18):

Section one:

A tiny island

appears on your finger

Section two:

prudently she moves

her neat pebble

Section three:

see on her back coins

she carries to heaven.

In general, students were able to unpack the metaphor in the first section. Initial predictions based on this section included such things as a mole, a wart, or a bug. Fewer students, however, were able to synthesise the evidence in the first two sections to enable them to unpack the metaphor comparing the ladybird’s body with a “neat pebble”. Fewer still could unpack the metaphors in the final section—that is, the comparison of the spots on the ladybird’s back to coins and the comparison of the ladybird flying into the sky to carrying the coins “to heaven”. Students tended to interpret the reference to coins either literally, or figuratively as representing wealth. Most recognised the reference to heaven as metaphorical, but interpreted this as referring to death rather than flying skyward.

However, some students were able to unpack the metaphors in all three sections to conclude that the poem described a ladybird. They were also able to explain their interpretations after their reading of each section. For example, after reading the first section one student predicted that the poem was describing a pimple, a speck of mud, or a bug. After reading the second section she refined her prediction to a bug, based on evidence that the poem was describing something that was alive. After reading the final section she concluded the poem described a ladybird, because it was referred to as “she” and because “the coins are the dots on the ladybird’s back. When she carries them to heaven it means she is flying.”

Engagement with texts and task

Engagement with the task

The capacity to make meaning from text is also related to engagement with texts and tasks. Overall, student responses recorded during the activities and the comments they made on completion suggested high levels of engagement and perseverance with the task when compared with reactions to many previous ARB resources. The resources described here differ from early ARB resources (and many other traditional comprehension activities developed for class use) in two main ways. One is the open-ended nature of the task; the other is that, for most of the poems, there is more than one answer that can be considered correct (in terms of being consistent with all the evidence in the poem). When the resources were sent out for trialling we did not provide teachers with the subjects of the poems, and we asked them to tell the students there was not necessarily only one possible “correct answer”.

Students’ comments suggested that it was the openness of the tasks, the challenges they posed, and the perseverance they required which motivated them. A common theme emerging from the analysis of these comments was that students saw themselves as detectives, or problem solvers:

It was fun because it was like a mystery that you had to solve. (Year 6 student)

It was like a jigsaw where you had to find the pieces that fitted together with each other. (Year 6 student)

The way it’s set out, it’s giving you a lot of information, but still it hides under its skin. (Year 10 student)

Thanks for the opportunity to think outside the square. (Year 10 student)

There was also evidence that students saw themselves as the makers of meaning rather than as passive recipients. One Year 10 student, who clearly saw herself as a theory builder, said: “Something I’m still wondering about is the last part. My theory makes sense until then.”

However, some learners, those perhaps used to more tightly defined comprehension tasks, seemed to be threatened by the open-ended nature of the tasks. These learners found it difficult to take a risk and step outside their comfort zone. Before we trialled the resources nationally we conducted trials with small groups. In one of these, a student became increasingly anxious, because he did not know the “right” answer and did not feel able to take a risk and make a guess. At another small group trial, a student also expressed frustration at not knowing the answer.

Engagement with texts

The meanings we construct from texts and our engagement with them are to a significant extent determined by our context, including our previous and current experiences. As one Year 10 student said: “I liked it [the poem] because I felt that I could relate to it.”

A good example of this came from our trials of the poem describing anger. We trialled the resource at two levels (Year 9 and Year 10) to determine which age group it best suited. It was interesting to note the differences between the responses. Year 9 students were more likely to make a literal interpretation—they tended to predict substances such as drugs or alcohol. The Year 10 students’ responses were broader, probably reflecting their growing awareness, experience, and understanding of different types of addiction, especially in the area of relationships. Their responses included a greater range of addictions, such as gambling, food, crime, and political correctness, as well as emotional states (such as rage, love, anger, revenge, and rivalry). Their explanations reveal their engagement with their chosen subject matter. For example, one student concluded that the poem was describing love, because:

It says that you ‘lose control’ and when you hit ‘the ground’ [that means] you split up and end the relationship and look at the ‘damage you’ve done’ [which is] the scars or the feelings hurt. (Year 10 student)

Another student thought it described either revenge or winning, because:

These can both be blinded by determination. You avenged yourself and realised it was wrong. But you have done damage. It could be emotional, physical, mental, or it could have stuffed up a relationship. (Year 10 student)

The use of te reo Māori in the poem describing a greenstone pendant challenged some students who were perhaps not familiar or comfortable with words from a language that they did not know. Some questioned the point of the Māori vocabulary but did not see it as an obstacle to interpreting the poem, while others did. Familiarity with the context of this poem and with the language content appeared to correspond with a positive engagement with the text.

A taonga has been given to a special person. It has been blessed by a priest. Aroha and spiritual things have been put in it to protect the special person because you treasure them. (Year 10 student)

Awhi is when you love or help someone. (Year 10 student)

I know it because it has stuff to do with our ancestors. (Year 10 student)

Conclusions

This article has focused on the factors that influenced students’ ability to make meaning from text as demonstrated in the trialling of English resources developed for the Assessment Resource Banks. These factors (basing interpretations and predictions on evidence in the text, changing predictions and interpretations in the light of new evidence, synthesising evidence within and across sections, understanding the use of vocabulary, interpreting figurative language, and engaging with texts and tasks) are not new. But focusing on students’ reasons for their responses, and on their thinking during and after reading, can provide useful information to inform further teaching and learning steps. It is beyond the scope of this article to describe these next steps. However, the ARB resources based on the poems described here provide ideas for next steps related to the specific needs highlighted in the trialling of each resource. Other useful starting points are Effective Literacy Practice in Years 1 to 4 (Ministry of Education, 2003) and the recently published Effective Literacy Practice in Years 5 to 8 (Ministry of Education, 2006).

References

Boom, C. (2003). If I were a storm. School Journal, 3(3), 18.

Dodat, F. (1987). Ladybug. In N. Farber & M. C. Livingston (Eds.), Three small stones (p. 18). New York: Harper and Row.

Dunstan, P. (1986). Behind the stars: Poems for children. Auckland: Hodder & Stoughton.

Greaney, K. (2004). Factors affecting PAT reading comprehension performance: A retrospective analysis of some Year 4–6 data. New Zealand Journal of Education Studies, 39(1), 3–21.

King-Wall, T. (1999). Greenstone pendant. In H. Kreyl (Ed.), The Wockagilla: Journal of Young People’s Writing (p. 23). Wellington: Learning Media.

Lai, M., McNaughton, S., MacDonald, S., Farry, S., Toloa, M., Kolose, T., et al. (2004, November). Profiling reading comprehension in Otara schools: A research and development collaboration. Paper presented at the 26th conference of the New Zealand Association for Research in Education, Wellington.

Miller, C. (2003). Anger. In R. Bright (Ed.), The Crazy Wai: Journal of Young People’s Writing (p. 17). Wellington: Learning Media.

Ministry of Education. (1994). English in the New Zealand curriculum. Wellington: Learning Media.

Ministry of Education. (2003). Effective literacy practice in Years 1 to 4. Wellington: Learning Media.

Ministry of Education. (2006). Effective literacy practice in Years 5 to 8. Wellington: Learning Media.

Powell-Chalmers, J. (2004). The scarf. School Journal, 3(1), 15.

Note

1&&&The format in which the poems are presented in this article is consistent with how they were presented to students. This format is not necessarily that of the poems as they originally appeared.

Sue McDowall is a senior researcher at the New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Email: sue.mcdowall@nzcer.org.nz

Verena Watson is a resource developer for the Assessment Resource Banks and a researcher at the New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Email: verena.watson@nzcer.org.nz