Beyond the gate: Community arts participation enhances teaching and learning

Ian Bowell

http://dx.doi.org/10.18296/cm.0003

Abstract

Participation in community arts projects has the potential to enrich and regenerate communities, and to support teaching and learning. This article draws upon data from six New Zealand case studies, made up of six different community arts projects, and examines the dynamic relationship between community arts projects and participating schools and youth centres. Qualitative data analysis reveals a link between a school’s or youth centre’s participation in community arts projects and enhanced teaching and learning for the educators and students involved. Evidence highlights the important role played by situated learning, community-based education, and teaching collaborations in engaging students and in supporting the professional learning of teachers and youth workers.

Introduction

Communities are better able to deal with change and address issues, such as social inequality, when people are engaged with community arts and cultural programmes (Dunphy, 2009). The ability of community arts projects to support the regeneration of communities is well documented (Bowles, 1989; Braden & Mayo, 1999; Landry, Greene, Matarasso, & Bianchini, 1996; Matarasso, 1997), with a body of literature emphasising the ability of community arts projects to enhance the renewal of communities (Andrews, 2011; Kay, 2000; Matarasso, 1998; Braak-van Kassteel, 2011; Williams, 1997). There is evidence that engaging in cultural and arts programmes transforms and revitalises both urban and rural communities (García, 2004; Evans, 2005; Evans & Shaw, 2005; Florida, 2002). Participation in community arts programmes is also linked to preventing youth disengagement (Longbottom, 2014; Pene & Ashley 2009; Burns, Colin, Blanchard, De-Freitas, & Lloyd, 2008). When youth are disengaged from school, work, family, and community they are at greater risk of homelessness, substance abuse, and mental-health issues; and social agencies view them as “at-risk”. Local community arts projects often provide support for schools and at-risk youth centres in the form of expertise to enhance teaching and learning (Andrews, 2011; Bowell, 2011, 2012; Ewing, 2010, Matarasso, 1997; van Kassteel, 2011). Participation in community arts programmes can be linked therefore to the enrichment, regeneration, and strengthening of communities, education, and engagement of youth.

This article, using analysed data from six New Zealand case studies of arts projects, examines how the participation of a school or at-risk youth centre in a community arts project can inform teaching and learning in the school and centre. The reported New Zealand-based research builds on research relating to participation in overseas community arts projects and its link to teaching and learning. In the United Kingdom, Matarasso (1997) evaluated a random selection of participants in a community arts project from more than 30 schools, and found participation in the arts had a positive impact on the educational performance of three out of every four students. When discussing the impact of arts partnerships between schools and the arts community, Andrews (2011) made the observation that the arts can raise student self-esteem, engage students, and increase arts learning and cultural appreciation. A report from the United Kingdom government’s Social Exclusion Unit noted that supporting participation in the arts and sports aids neighbourhood renewal through improved performance on indicators of health, crime, education, and employment (Department for Culture, Media and Sport, 1999). In the Netherlands, Braak-van Kassteel (2011) discussed a variety of community arts projects, viewing them as bridges between learning opportunities inside and outside the school, between school and family culture, and between home and the world outside. In Australia, Hunter (2005) reviewed six research projects whose aim was to gather evidence on the impact of arts participation on students’ learning and development and found that arts participation had a positive impact on students’ development. The report highlighted the role arts projects played in providing professional support for teachers through the development of collaborative partnerships between students, teachers, artists, families, and communities. This evidence suggests a school’s participation in community arts projects can enhance teaching and learning. A range of community arts projects are undertaken throughout New Zealand, although there is little research relating to the potential of enhanced teaching and learning within schools participating in those initiatives.

Cultural centres support teaching and learning

Increasingly, museums and galleries have become associated with community regeneration through community arts projects, including in New Zealand. The term cultural centres is often used to describe museums and galleries, and for the purpose of this article I will use this term when describing museums and galleries. Cultural centres have become cultural brokers, coordinating and instigating arts-based projects within their local communities.

Cultural centres’ support for local communities is also evident in the work they do with schools and youth groups. Frequently, support for teachers and youth workers is seen where museum and gallery education is offered within the cultural centres. For example New York’s Museum of Modern Art offers teacher professional development programmes, and in 2010 London’s National Gallery ran a literacy programme for local primary schools. Davies (2010) noted the use of cultural centres (children’s theatres and museums) helped student teachers develop confidence in the teaching of the arts. In New Zealand museum and gallery educators provide a range of practical support to local schools. Student and teacher programmes are linked to the changing exhibits in the cultural centres. For example, Pataka Museum/Art Gallery Porirua maintains a varied programme supporting curriculum delivery in local schools through student programmes and teacher professional development. The educators use a combination of exhibitions and arts practitioners to provide an engaging mix of educational programmes, which reflects Porirua as one of the most culturally diverse cities in New Zealand. The Christchurch City Art Gallery, despite being closed due to earthquake repairs, continues to run school programmes using outreach lessons in schools and around the city, linking these outreach sessions to the gallery’s collection. In South Auckland, community arts expertise is used to support rangatahi (youth) in the Ngä Rangatahi Toa Creative Arts Initiative (Longbottom, 2014). The initiative is an alternative education scheme using arts practitioners to mentor rangatahi to enable successful transition into tertiary education, employment or back into mainstream school.

Given that community arts projects are a part of New Zealand’s educational landscape, a number of research questions might be asked about the role played by community-based arts education in New Zealand. The central question guiding this research is: What effect does a school or at-risk youth centre’s participation in a community arts project have on teaching and learning? If community arts programmes are able to address contemporary social challenges and programmes in cultural centres are able to support local schools deliver the curriculum, how is teaching and learning informed when schools or youth centres take part in these programmes? Can the ability of community arts projects to enrich and regenerate communities described by Andrews (2011), Kay (2000), Matarasso (1998), van Kassteel (2011), and Williams (1997) extend to teaching and learning in schools and youth centres?

Case studies

The research project informing this article began in New Zealand in June 2012 and was situated in three New Zealand cities. The project set out to discover the effect of participation in community arts projects on teaching and learning in schools or in at-risk youth centres. This article presents and considers analysed qualitative data collected from the project’s six case studies which were:

•Matariki mural project

•Masked parade project

•Kinetic sculpture/dance project

•Prayer flag project

•Beach murals project

•Photography project.

The Matariki mural project took place in June 2012 and was instigated by a local community centre organiser. The city’s arts council funded the project and a local community artist organised local primary, intermediate, and high-school students to design and paint the mural. The mural depicted the story of Matariki (Mäori New Year) and was painted on the outside wall of a primary school’s classroom, next to a public footpath, making it visible to the public. This case study focused on the four schools involved in the design and painting of the mural.

The masked parade project took place in December 2012. The parade is the opening event of an annual arts festival. Each year the parade adopts a theme, which participants interpret through costume and mask. In 2012, the theme was “myths and legends”. Community groups are encouraged to take part in the parade, with the majority of participants coming from local schools. This case study focused on one primary school’s participation in the 2012 masked parade. The whole school (424 children) worked for 10 weeks on their entry, integrating their mask and costume design work into their teaching programme.

The kinetic sculpture and dance project was associated with an exhibition of Len Lye’s kinetic sculpture at a public gallery, and took place in April 2013. The gallery’s education department organised the project, and a dance education organisation offered a programme to local primary schools that involved students responding to the kinetic sculptures through dance. The children’s choreographed responses, performed in the gallery space during their visit, were facilitated by the gallery educator and a dance education expert. This case study focused on four classes from one participating primary school.

The prayer flag project took place in May 2013. A public museum and gallery co-ordinated the project in conjunction with a community artist, who also designed the project. The project involved the artist working with students from local schools to design and make flags in the style of Buddhist prayer flags. Each student created a design representing their concerns and hopes for their community. The designs were realised as woodblocks and printed on the flags. The project’s goal was to hang the resulting 3000 flags in the community during their arts festival. This case study focused on three secondary schools’ participation in the project.

The beach mural project, completed in February 2014, was instigated and coordinated by a city council arts and heritage officer. A beachside playground had been re-landscaped, and consultation with the city’s youth council identified a need for an area for local youth to congregate. To accommodate this need an outside stage and picnic area was designed. The final component of the design was a series of large panels forming a screen. These panels could be replaced, and the concept was for local schools and youth groups to create artworks on each panel. The case study focused on two high-school classes and an at-risk youth centre’s involvement in the beach project.

The photography project, completed in June 2014, was instigated by a photographer who worked with an at-risk youth alternative education centre. Funded by a local government community arts fund, the project involved the photographer working with the at-risk youth enabling them to express their identity through photography. The at-risk youth used analytical tools associated with photography to express their identity within the local community. This case study focused on the youth centre, youth centre staff, and the photographer.

Research design

The research project used a multiple case-study methodology (Yin, 2006, 2009), which allowed me to focus on six different community arts projects whose participants were from local schools or youth centres. The context of each community arts project varied and using a multiple case study methodology allowed me to consider the variables in each case study and range of associated data.

Data in the form of semistructured interviews, observations, and focus-group discussions were collected from participants in each case study and analysed for evidence that might indicate an impact upon teaching and learning within each school or youth centre during and after taking part in the community arts project. Themes generated from the initial analysed data from each case study were compared to discover if evidence from the six case studies was convergent.

For the purpose of this article I will focus on data generated from the interviews and focus group discussions and use excerpts to support the analysis. Semistructured interview questions focused on how the community arts projects were instigated, structured, and managed, as well as the relationship between the teachers and students in the school or youth centre and the community arts projects. Focus-group discussions focused on any links the participants could make between participation in the community arts projects, and teaching and learning.

Across the six case studies, 34 semistructured interviews and two focus-group discussions were conducted. Interviewees either worked in schools, at-risk youth centres, cultural centres, or community organisations. They included teachers, youth workers, gallery educators, community artists, and community arts managers and workers. The first focus group consisted of one teacher, two gallery educators, and one community artist; the second focus group comprised one gallery educator, one community artist, and one teacher. This article provides an interpretation of the views expressed by the interviewees focusing on the link between participation in community arts projects and enhanced teaching and learning.

Semistructured interviews and focus-group discussions were transcribed and this data analysed using a system of open coding (Denscombe, 2005; Ryan & Bernard, 2003; Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Cross-case analysis of data identified the following four themes common to the six case studies:

•communities supporting schools/at-risk youth centres

•collaboration

•teacher learning

•student learning.

These four themes were used as codes to re-analyse the data. The following four sections highlight how interviewees’ responses link to the common themes.

Communities supporting schools/at-risk youth centres

Interviewees talked about the important role of schools and at-risk youth centres within their local community. The community centre organiser involved in the Matariki mural project commented:

I wanted to see the connection between primary school and intermediate and high school that was important for me to see the kids coming together and taking ownership of their area … connecting the schools and the communities and pulling them into working cohesively.

The community centre used the mural project as a vehicle to encourage local school students to become involved in, and connected to, their community. The community centre organiser used the design and painting of a public mural depicting the celebration of a cultural event as a way of developing a sense of community. A teacher of te reo Mäori involved in the same project commented:

Fostering a sense of community is really important for our Mäori students to be involved within the community as part of contributing back.

Both the organiser and teacher believed participation in this project fulfilled their goal of enabling students to become actively involved in their local community.

Teachers and youth workers involved in the beach mural project emphasised the importance of the students being given the opportunity to have their voice heard. They believed this process was an important ingredient in developing the students’ relationship with their local community and is a reflection of their work with students. The council officers saw their role as giving students and local youth the opportunity, through the project, to engage with the community and foster the development of their social wellbeing by having their voice heard. A student who took part in the project said:

I think it is cool to share our work with the public. I think people will be impressed that it came from such young students.

And a community arts organiser said:

It helps them to build a better world view and they have done something they are connected to.

The community arts organiser made the connection between students’ participation in the project and their development of a greater understanding of their community. Both the community and the students benefit from the community project: the students from a greater understanding of community involvement; the community from a public artwork. The local community may also view the youth involved in the project positively as they associate their improved environment with the work and effort of those involved. The council officers also talked about the students making their mark, both literally and metaphorically, within their local community. In the photography project the students produced a poster that depicted the work of the at-risk youth centre and the role the students took within their community. One of the youth workers involved in the project said:

It is going up in a public space. Some of them took their family down to have a look. They liked the idea of it being up somewhere so people could see what they were doing.

Teacher and youth worker interviewees expressed the view that students should be encouraged to be actively involved within their local community. They felt one function of participating in a community-based arts project was the opportunity for students to become active within the community. Within all six case studies the teacher and youth worker interviewees emphasised the way schools and at-risk youth centres provide a focal point for diverse community groups within their community. Interviewees from cultural centres, community organisations and councils, and community artists, emphasised that supporting schools, centres for at-risk youth, and students within their community was an integral part of their role. Teachers and youth workers highlighted the importance of schools and at-risk youth centres being actively involved within their community.

Earlier I highlighted a range of literature linking engagement in community arts programmes and their ability to regenerate communities and engage youth. Analysis of interviews and focus-group discussions from all case studies point to the interviewees believing participation in community arts programmes as having a positive impact on the participants and community. Interviewees were youth workers, teachers, community managers, museum educators, and community artists. The evidence revealed in the data suggests the interviewees view community arts programmes as tools to realise their goal of developing their local communities and engaging youth; also, of enhancing school–community relationships.

The school principal involved in the masked parade project commented:

Part of our role is to develop a sense of community, and schools are the hub of that community.

One of the gallery educators from the prayer flag project made the following comment:

Seeing the gallery as a place where a group or a community can meet... galleries and museums should be a meeting place and that community should have ownership of and learn something new or they will be challenged with things. I see myself as a connector, the person who is bringing the opportunities to educators and students or to the artist.

Both the school principal and the gallery educator talked about the part played by schools and cultural centres in developing local communities. The gallery educator talked about “bringing together opportunities” and the school principal talked about the school’s ability to “develop a sense of community”. Both roles complement each other. The two interviewees have a common belief and commitment to developing and building local communities through participation in community arts projects. The relationship between cultural centres and schools must be interdependent if their goal of developing their local communities is to be realised.

Collaboration

Data analysis highlighted the importance the educators, youth workers, and managers placed on collaboration in developing a community arts project. In each case study a community group or cultural centre brought together separate community groups to focus on a common theme through an arts activity. Interviewees talked about collaboration when answering questions about the organisation of, or participation in, community arts projects. Analysis of the data revealed that collaboration was described as collaboration between:

•community groups

•teachers

•teachers and experts

•students

•youth workers and community groups.

When teachers and youth workers talked about collaboration, they focused on the opportunity to collaborate with other teachers within their schools and experts outside the school or youth centre. A teacher from the masked parade project commented:

We met in our groups … It was co-operative and nice to work with other teachers.

A teacher from the Matariki mural project also highlighted the importance of collaboration in sharing expertise, commenting that:

You get to work with other people with different talents and strengths and you don’t get to do that all the time.

Teachers also talked about students collaborating with one another and the impact of this upon student learning. The principal involved in the masked parade project commented:

Our older children were working alongside our younger children helping them and supporting them.

In each case study students were required to work collaboratively on the projects. They were asked to discuss ideas and develop a creative response, such as a mural design, a choreographed movement, or a mask design. Individual creative contributions became part of the group’s collective response. Responding collectively mirrored the organisation of community arts projects and the way communities respond to their environment. A teacher from the Matariki mural project commented:

everyone using their skills, feeling valued and proud of the whole project; it is better that you have everyone on board and everybody’s input.

During the photography project the students developed a routine where they reflected on the images they took as a group. When describing this process the photographer involved in the project said:

They pulled together more. They had more of a joint voice. It was empowering them and if they agreed with each other they felt empowered by that as a group.

The photographer made the point that the process of the students working collaboratively to reflect on their photographs helps these students to develop. They had a common goal and were working as a group to present their ideas to the community.

Interviewees talked about what they had learnt as a result of working collaboratively. They talked about learning from each other and from the expertise of others involved in the collaboration. Experts such as the artists and the cultural centre educators talked about how they had learnt from working with students, teachers, youth workers, and others within the context of the projects. The evidence suggests the success of community arts projects is reliant on collaboration and when those involved collaborate this informs teaching and learning. Interviewees’ link success of the community arts projects to being given the opportunity to enrich their professional practice. It may be the case that participants are more likely to participate in future projects because they know it will inform their own professional development. It would appear the participants goals of building their local communities is realised through participating in community arts projects and this in turn informs their professional practice.

Teacher learning

Teacher and youth worker interviewees talked about the collaborative process informing their own professional development. Each school or youth centre approached the project with staff collaborating and using their expertise within their institution, as well as collaborating with experts outside. When the teacher and youth worker interviewees talked about seeing other experts working with the students, they emphasised how the teachers and youth workers learnt from that experience. For example, in talking about the kinetic sculpture dance project, one teacher involved in the project said:

Being so close to these expert people you (the teacher) get more technique and more confidence to carry out those things yourself.

During the photography project the photographer developed a close working relationship with the students. When he talked about how he went about working with this group of students he said:

In order to give you a degree of respect knowing you are coming to give them your knowledge and expertise … becoming a participant they included you more.

The photographer learnt that to work with this group of at-risk youth he needed to gain their trust by becoming a participant in their centre rather than just a teacher of photography.

The teachers related the process of observing experts working with the students to the development of their own professional competence. They emphasised how the experience of being part of a project informed their own practice after the completion of the projects. When describing how the Matariki mural was used once completed, a teacher from the project said:

I know the teachers have gone over there and used it and talked about the story and gone back to the classroom and written about it.

Teachers used the visual metaphors contained in the mural as a teaching resource within the school once the mural project had been completed. As well as depicting the story of Matariki, the mural contained visual references to the history of the local landscape and its importance to local Mäori. Images within the mural were visual metaphors for Mäori concepts. The teacher went on to say:

There is symbolism in all parts of the mural. To participate in a Mäori piece of art it has significance to all cultures about the explanation of creation, sharing different versions of creation and Whakapapa (genealogy) so they can talk about where they come from and their own stories.

The mural was created using the collective knowledge and expertise of the local community. Once completed, themes from the mural informed the teaching and learning of teachers and students within the school. The mural also went on to support the delivery of a range of leaning areas including, Social Studies, The Arts, English, and Learning Languages.

Interviewees emphasised the importance of collaboration with experts to support the projects. During the early stages of the masked parade project the school consulted with local community experts on Mäori protocols. The school broadened its learning community beyond the school gates using community expertise. An art materials supplier and the local council provided support in the form of workshops on designing and making masks. The local council also organised local businesses to donate materials to the schools for mask making and costume design. The community arts project therefore brought together various threads of the community to realise the masked parade.

The importance and interconnection of collaboration and teacher learning in the participating teachers’ experiences is evident in the data, as teachers describe the collaboration on arts education projects as supporting their teacher learning. This finding supports, and at the same time is explained in, literature that similarly highlights this connection. Creating a collaborative teaching community to support teacher learning is described in a range of literature (Crebbin, 2004; Huberman, 1993; Lieberman, 1996; Loewenberg Ball & Cohen, 1999; Talbert & McLaughlin, 2002; Timperley & Robinson, 2002). This literature discusses how teachers develop confidence in teaching by working in collaborative groups towards common goals. Analysed data from these six case studies highlighted the importance teachers and youth workers place on collaboration with experts within and outside schools and youth centres. Literature describing community arts projects emphasises their ability to enrich and regenerate communities (Andrews, 2011; Bowles, 1989; Braak-van Kassteel, 2011; Kay, 2000; Matarasso, 1997, 1998). The literature describing collaborative teaching communities and the literature describing community arts projects attribute an increase in participants’ confidence to the process of collaboration. The interviewees highlighted the importance of working with experts both inside and outside school as a way to develop confidence in teaching, which reflects the literature’s findings.

Student learning

Data analysis identified two categories of student learning: student learning during the project and student learning once back in the classroom or at-risk youth centre. Teacher and youth worker interviewees in particular talked about students learning in groups and in some cases learning in groups across a range of ages. For example, the mural project was organised into working groups comprising students from primary, intermediate, and high school. Older students took responsibility for supporting younger students. The community artist who was part of the Matariki mural project said:

A lot of social learning that went on particularly for the teenagers; for the boys there was that responsibility and they took that seriously.

The boys she referred to took responsibility for designing a stylised wëtä (native insect) for the mural. They created a stencil of their design and the younger students worked with the older students to manufacture the stencils and use them to create the mural. The collaborative nature of the projects gave teachers the opportunity to organise how the students would work together, resulting in students supporting one another.

In relation to learning about the arts, interviewees talked about students learning about the collaborative process of creating a work as well as learning about arts-specific techniques. The cultural centre educator involved in the prayer flag project commented:

I hope they learn that this is an art process. That collaboration and the idea of being a part of the collaboration that they learn, it is a process that isn’t necessarily about sticking a painting on a wall in a gallery, it is a practice that involves a community, creating a community that creates an artwork.

The educator emphasised the creation of an artwork within a collaborative setting, which she calls a community. A link is made between creating an artwork collaboratively and working within a community towards a common goal. The community centre organiser talked about connecting the schools to their local community (see above, Communities Supporting Schools/Youth Centres). The cultural centre educator talked about working within a community on a common goal. The underlying belief in these examples is that working collaboratively towards a common goal within a community setting can develop the students’ understanding of how communities can effect change.

Although the focus of these projects was the arts, often the primary school teachers talked about how learning associated with the projects informed other learning areas. One of the teachers from the masked parade project said:

It was integrated into other areas of literacy and writing and everything else.

The school that took part in the masked parade project integrated its work on the project into classroom teaching for the 10-week term. Curriculum integration is common in primary schools and reflects their approach to teaching a crowded curriculum. Taking part in the masked parade was not seen by the school as an added extra but part of their everyday teaching. The principal of the school taking part in the masked parade said:

The project lent itself to integration … they learnt the Key Competencies from the curriculum, Working Together, Managing Themselves, cross school co-operation and collaboration is really important.

Interviewees talked about the projects’ “real” or “authentic” setting, motivating students and enabling them to learn. One of the teachers involved in the prayer flag project said:

This is a real thing happening in real time and there is something exciting about that.

According to Lave (1988), learning is a function of the activity, context, and culture in which it sits. She calls this situated learning. A critical component of situated learning is social interaction, where learners become involved within the site and activities associated with that site. The data indicate interviewees attribute student and teacher learning to the projects being real or situated. Some researchers (Brown, Collins, & Duguid, 1989; Lave & Wenger, 1991) developed the theory of situated learning further, emphasising the concept of “cognitive apprenticeship”, which describes learners developing and using skills in an authentic setting. They make the point that learning advances via collaborative social interaction and the social construction of knowledge. Data used to inform this article highlight the importance the interviewees attach to the effect of collaborative social interaction and the context of the community arts projects in students’ learning. They talk about students’ leaning from the expertise of others within an authentic setting.

Conclusion

This article set out to discover the effect on teaching and learning in schools and at-risk youth centres when participating in community arts projects. Participating educators from schools or at-risk youth centres talked about their role in and the importance of developing local communities. Analysis of the data revealed interdependence between schools or at-risk youth centres and cultural centres or community organisations. Each needed to collaborate to realise their common goal of enriching their local community.

Interviewees emphasised collaboration as an important element in the success of each community arts project. Literature describing collaborative teaching communities (Crebbin, 2004; Huberman, 1993; Lieberman, 1996; Loewenberg Ball & Cohen, 1999; Talbert & McLaughlin, 2002; Timperley & Robinson, 2002) and community arts projects (Andrews, 2011; Bowles, 1989; Kay, 2000; Longbottom, 2014; Matarasso, 1997, 1998; Braak-van Kassteel, 2011) highlights the importance of social interaction as a vehicle for change for participants in those communities or projects. Change can be seen in teacher–student learning, or social change within a community. The interviewees talked about becoming more confident in teaching through their interaction with each other and experts, and this growing confidence supported teacher and student learning.

In discussing collaborative teaching communities, Glazer and Hannafin (2006) describe a supportive community of practice where teacher leaders act as mentors to develop confidence and expertise within their learning community. The process is one of acculturation as teachers gain expertise within a social setting. Within the context of the six case studies, the teachers and youth workers extended their community of practice beyond the gates of the school or at-risk youth centre. Interviewees talked about the opportunity for participants to bring their own understanding and knowledge to the projects. Each project allowed its participants to share knowledge and generate a new understanding of the project’s content which went on to inform teachers’ and students’ future learning back in their schools.

Data also highlighted the importance of situated learning and community education in supporting teaching and learning. All interviewees emphasised the link between learning and community arts projects being real or situated. Participants were able to use their own knowledge and understanding within the context of their community. Participation in the community arts projects had been the catalyst to engage students within authentic settings.

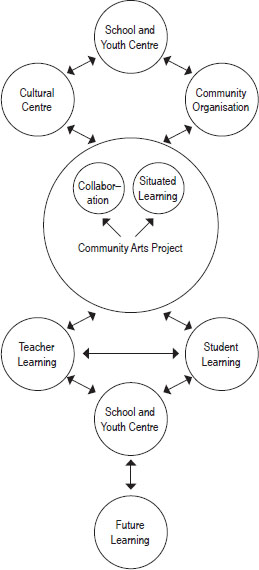

Analysis of data from the six case studies revealed a process where community arts projects informed teaching and learning. When a school or at-risk youth centre worked with either a cultural centre or community arts organisation and collaborated in a community arts project, teaching and learning reflected principles of situated learning. A foundation was provided for future learning. As a result of their participation in a community arts project, teachers’ and youth workers’ own learning was informed by student learning, as well as students learning from teachers and youth workers (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Community arts projects informing teaching and learning

Analysis of data from these six case studies has revealed a model that describes how teaching and learning can be informed by a school’s or youth centre’s participation in community arts projects. The model is continuous as future learning can feed back into participation in other community arts projects.

Earlier I asked the question whether the ability of community arts projects to enrich and regenerate communities extends to teaching and learning in schools and youth centres. In each case study the teacher or youth worker interviewees discussed how their practice had been informed through participating in the projects. They talked about how the students had not only gained a greater understanding of the specific context of each community arts project, but were able to use this understanding to inform their future learning. A school or youth centre’s participation in community arts projects informed and enriched student and teacher learning.

It can be a challenge supporting students to understand their community and develop tools that will help them become successful participants within that community. Evidence from these six case studies demonstrates that a school’s or at-risk youth centre’s participation in community arts projects beyond their gates can be a powerful tool in supporting educator professional learning and collaboration as well as student learning about and in the arts.

References

Andrews, B. (2011). The good, the bad and the ugly: Identifying effective partnership practices in arts education. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 1(13), 38–46.

Bowell, I. (2011). Supporting visual art teaching in primary schools. Journal of Art Education Australia, 34(2), 98–118.

Bowell, I. (2012). Research report: Community engagement enhances confidence in teaching visual art. Wellington: Ako Aotearoa National Centre for Tertiary Excellence.

Bowles, J. (Ed.). (1989). Developing community arts: An evaluation of the pilot National Arts Worker Course. Dublin: CAFE.

Braak-van Kassteel, I. (2011). The role of community art projects within and without the school curriculum. Exedra: Revista Cientifica, 3(2), 55–74.

Braden, S., & Mayo, M. (1999). Culture, community development and representation. Community Development Journal, 34(3), 191–204. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/cdj/34.3.191

Brown, J. S., Collins, A., & Duguid, P. (1989). Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18(1), 32–42. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/0013189X018001032

Burns, J. Colin, P. Blanchard, M. De-Freitas, N. & Lloyd, S. (2008). Preventing youth disengagement and promoting engagement. Perth, WA: Australian Research Alliance for Children & Youth.

Crebbin, W. (2004). Quality teaching and learning: Challenging orthodoxies. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Davies, D. (2010). Enhancing the role of the arts in primary pre-service teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26, 630–638. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2009.09.011

Denscombe, M. (2005). The good research guide for small scale research (2nd ed., pp. 89–92). Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Department for Culture, Media and Sport. (1999). Arts and communities: The report of the national inquiry into arts and the community. London: Community Development Foundation.

Dunphy, K. (2009). Developing and revitalizing rural communities: Australia. Creative City Network of Canada.

Evans, G. (2005). Measure for measure: Evaluating the evidence of culture’s contribution to regeneration. Urban Studies, 42(5), 959–983. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00420980500107102

Evans G., & Shaw, P. (2004) The contribution of culture to regeneration in the UK: A review of evidence. [Report to the Department for Culture, Media and Sport.]London, England: London Metropolitan University.

Ewing, R. (2010). The arts and Australian education: Realising potential. Australian Education Review, 58. Retrieved from http://research.acer.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1020&context=aer

Florida, R. L. (2002). The rise of the creative class: And how it’s transforming work, leisure, community and everyday life. New York, NY: Basic Books.

García, B. (2004). Cultural policy and urban regeneration in Western European cities: Lessons from experience, prospects for the future. Local Economy, 19(4), 312–326. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0269094042000286828

Glazer, E. M., & Hannafin, M. J. (2006). The collaborative apprenticeship model: Situated professional development within school settings. Teaching and Teacher Education, 22, 179–193. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2005.09.004

Huberman, M. (1993). The model of the independent teachers’ professional relations. In J. W. McLaughlin (Ed.), Teacher’s work: Individuals, colleagues and contexts (pp. 11–50). New York: Teachers’ College Press.

Hunter, M. A. (2005) Education and the arts research overview. Surry Hills, Sydney, NSW: Australia Council.

Kay, A. (2000). Art and community development: The role the arts have in regenerating communities. Community Development Journal, 35(5), 414–424. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/cdj/35.4.414

Landry, C., Greene, L., Matarasso, F., & Bianchini, F. (1996). The art of regeneration: Urban renewal through cultural activity. Stroud, UK: Comedia.

Lave, J. (1988). Cognition in practice: Mind, mathematics, and culture in everyday life. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511609268

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511815355

Lieberman, A. (1996). Practices that support teacher development: Transforming conceptions of professional learning. In M. McLaughlin & I. Oberman (Eds.), Teacher learning: New policies, new practices (pp. 185–201). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Loewenberg Ball, D., & Cohen, D. (1999). Developing practice, developing practitioners: Towards a practice-based theory of professional education. In L. Darling-Hammond & G. Sykes (Eds.), Teaching as the learning profession: Handbook of policy and practice (pp. 3–32). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Longbottom, S. (2014). Love lives here: Realising rangatahi potential. In V. Carpenter & S. Osborne (Eds.). Twelve thousand hours: Education and poverty in Aotearoa New Zealand (pp. 246–252). Auckland: Dunmore Publishing.

Matarasso, F. (1997). Use or ornament? The social impact of participation in the arts. Stroud, UK: Comedia.

Matarasso, F. (1998). Poverty and oysters: The social impact of local arts development in Portsmouth. Stroud, UK: Comedia.

Pene, S. & Ashley, M. (2009). Enhancing learning and confidence for Maori through community participation. Wellington: Ako Aotearoa National Centre for Tertiary Excellence.

Ryan, G., & Bernard, R. (2003). Data management and analysis methods. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Collecting and interpreting qualitative materials (pp. 259–309). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Talbert, J., & McLaughlin, M. (2002). Professional communities and the artisan model of teaching. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 8(3/4), 325–343. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/135406002100000477

Timperley, H., & Robinson, V. (2002). Partnership: Focusing the relationship on the task of school improvement. Wellington: NZCER.

Williams, D. (1997). How the arts measure up: Australian research into the social impact of the arts. Stroud, UK: Comedia.

Yin, R. (2006). Case study methods. In J. Green, G. Camilli, & P. Elmore (Eds.), Complementary methods in education research (pp. 115–117). Mahwah, NJ: LEA.

in, R. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (4th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

The author

Ian Bowell is a lecturer and centre coordinator at the University of Canterbury’s Nelson campus. His current research interest is the link between student engagement and participation in community arts programmes.

Email: ian.bowell@canterbury.ac.nz