A call for investment in high-quality, culturally sustaining early childhood provision as a public good

Jenny Ritchie

This article examines how government policies have undermined equity and access in early childhood care and education in Aotearoa. While flaxroots initiatives have historically fostered inclusive, community-centred, low- or no-cost early childhood models, recent policies favouring commercial providers have intensified disparities, particularly for Māori and Pacific communities. The analysis situates these developments within broader patterns of structural injustice and cultural erosion, especially for Māori. It argues for renewed government commitment to early education as a public good, in order to ensure funding of provision that honours cultural identities, supports linguistic revitalisation, and meets the realities of an increasingly diverse population, positioning early childhood care and education as a vital public investment and foundational education pillar of a just society.

Introduction

Despite a long-standing governmental commitment to fund, regulate, and ensure equitable access to the school sector, early childhood care and education (ECCE/ECE) in Aotearoa (New Zealand) has historically remained marginalised, positioned outside of the compulsory education system. Western gendered ideologies have assigned responsibility for the care and education of young children to mothers within the home, yet in Aotearoa, a diverse early childhood sector has emerged in response to community needs in the form of flaxroots, community-led initiatives. These include the free kindergarten movement, playcentre, non-profit community and home-based childcare services, kōhanga reo, and Pacific language nests, all of which have aimed to support both children and families via progressive, inclusive pedagogies, keeping costs to families as low as possible. Although research consistently affirms the social, educational, and economic short- and long-term societal benefits of high-quality, culturally responsive early education (Bakken et al., 2017; Bauchmüller et al., 2014; García et al., 2021; McCoy et al., 2017), policy and funding frameworks have often constrained the sector’s potential to provide equitable support to children and families.

However, in recent decades, government policy and funding decisions have led to the current dominance of private, for-profit providers, exacerbating inequities, particularly for Māori and Pacific communities. This has coincided with declining enrolments in not-for-profit community-based services such as kindergartens, playcentre and kōhanga reo (Education Counts, 2015). Although the government invests $2.3 billion annually in ECE, one of the highest per capita funding levels in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), our provision remains among the least affordable (Duff, 2023). That the five largest for-profit providers receive nearly 20% of government funding whilst reporting substantial profits, highlights how government policies have enabled this corporate capture of what should instead be public investment in our children, families, and their futures.

Structural inequities, rooted in colonisation, and embedded and perpetuated in our education system, continue to disadvantage Māori and Pacific communities (Bishop & Glynn, 1999). Achieving educational equity requires acknowledging historical and structural injustices, particularly those impacting Māori, whose land, language, and cultural foundations have been systematically eroded. Prioritising the inclusion of high-quality te reo Māori within early learning environments is essential for restoring what has been lost (Skerrett, 2021). Furthermore, a truly equitable approach must respond to the unique, diverse needs of children and families in our current context of superdiversity (Chan & Ritchie, 2023). A reassertion of government responsibility for public ECE provision, inclusive of te reo Māori and responsive to superdiversity, is essential for achieving social and cultural justice and to upholding the progressive educational legacy of ECCE in Aotearoa. Accordingly, this article calls for a collective commitment to restoring the progressive, inclusive vision of early education in Aotearoa, and investment in high-quality, culturally sustaining early childhood provision as a public good.

Background to early childhood provision in Aotearoa

Since the 1877 Education Act, New Zealand governments have accepted their core responsibility to fund, regulate, and evaluate the school sector, employing qualified teachers, and ensuring schooling is accessible to all, without requiring families to pay for the right for their children to attend their local schools. However, successive governments have continued to position ECCE outside of the compulsory schooling sector, keeping a firm boundary between schools and early childhood provision. This was originally justified under the patriarchal ideology assigning the care of young children to their mothers, to be conducted in private homes. Yet, many middle-class women found this to be a lonely, isolated, under-appreciated and un-remunerated situation, whilst working women had few options to ensure the care of their young children.

In response to this exclusion from government provision there arose a series of flaxroots initiatives (i.e., kindergarten, playcentre, kōhanga reo, Pacific language nests) led by women and families, to meet the needs of their communities, by providing support for both women and young children. The free kindergarten movement was at the forefront of this leadership, emerging firstly in the 1870s–1880s, “initiated by progressive citizens in the main settlement cities” whose philanthropic concerns extended to the wellbeing and education of young children (May & Bethell, 2017, p. 2). As Helen May explains:

Nineteenth century philanthropy concerns had various strands, stemming from a legacy of enlightened understandings about the care of neglected children and their lost potential to society. Educating the young children of the urban poor in kindergartens, was not only motivated by rationales of child rescue, but was also a demonstration of the intellectual potential of all children irrespective of class. (May, 2015, p. 34)

This progressive agenda promoted access to quality ECCE provision for all children, but particularly for those who would otherwise be excluded from such opportunities, an early example of social justice. The vision of the early kindergarten movement “was to influence and shape the education of young children as democratic citizens” (May & Bethell, 2017, p. 19). The kindergarten movement built on its original Froebelian ideas and materials, adding in contributions from the pedagogical approaches of visionaries such as John Dewey, Maria Montessori, and Susan Isaacs. These pedagogies affirmed children as active learners, focusing on child-centred, free, and collaborative play as well as fostering socio-emotional wellbeing. Such innovative ideas were hugely impactful in transforming traditional top-down education methods to the strong focus on child- and whānau-centred pedagogies that we see elaborated in the early childhood curriculum, Te Whāriki (Ministry of Education, 1996, 2017).

We know from both national and international research evidence that high-quality, culturally responsive ECCE is hugely beneficial, and especially so for children whose home lives and circumstances are less able to support their growth and learning (Bakken et al., 2017; Shonkoff, 2017; Wylie & Thompson, 2003). We also know that these benefits are not just seen in the immediate enhanced wellbeing of children, but in their longitudinal life trajectories and those of the wider society (García et al., 2021; McCoy et al., 2017). High-quality, culturally responsive ECCE is social justice; that is, social and cultural equity in action.

Impacts of neoliberal policies on the early childhood sector

As has been so well analysed in the scholarship of Helen May (see, for example, 1992, 2013, 2015, 2020) and Linda Mitchell (see, for example, 2002, 2011, 2014, 2019a), our wider early childhood sector including the kindergarten movement, along with teacher education provision, has been hugely influenced by the pendulum of government policies that have constrained funding and forced an amelioration of the progressive potential of our services to provide crucial support for children and families.

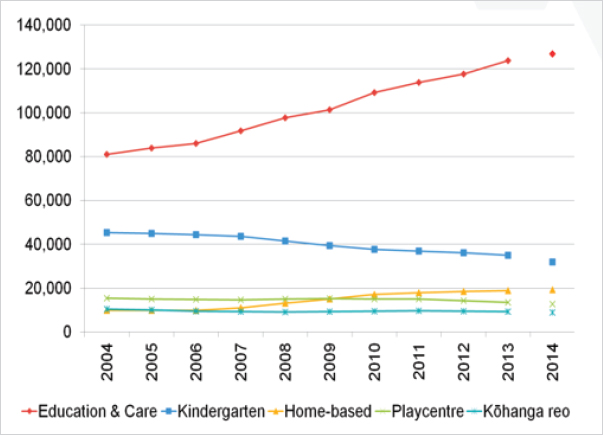

The result of government policies supporting private provision is indicated in Figure 1, which demonstrates changes in service provision between 2004 and 2014.

Whilst this 2014 Education Counts early childhood census report does not distinguish the proportions of for-profit “education and care”1 services, it is clear that this growth had impacted kindergarten enrolments in that decade. It could be surmised that government policies were aimed at expediently providing spaces for young children, and the economic benefits of enhanced workforce availability for their parents, through enabling the growth of private and corporate provision. A 2014 submission by NZEI Te Riu Roa identified that:

this rapid increase in for-profit provision has come at the expense of quality, and impacted negatively on effectiveness and efficiency. Labour [teachers’ salaries] is the biggest cost in the provision of ECE, and the profit motive incentivises service providers to cut labour costs. Yet high-quality ECE provision is entirely dependent on high-quality staffing. (NZEI Te Riu Roa, 2014, p. 4)

The submission also reiterates what is well-established in the research, that poor quality early childhood provision undermines governments’ stated intentions to improve schooling achievement outcomes, and impedes their “long-term economic goals, as poor quality ECE leads to higher costs associated with crime, welfare and health and lower income from taxes” (NZEI Te Riu Roa, 2014, p. 4).

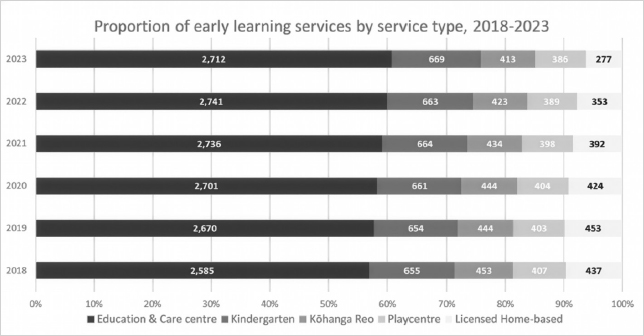

A decade later, the 2024 Early Childhood Census recorded 2,666 “education and care” services, again not distinguishing between for-profit and community-based centres (Education Counts, 2025). However, whilst this “education and care” slice of the sector is now hugely dominant, since 2019 the number of licensed home-based services had markedly decreased by 45% to 248, with 416 kōhanga reo remaining, a 6% decrease, along with 382 playcentres, a 5% decrease. Kindergarten numbers had increased from 654 to 674. Meanwhile, the 2023 Early Childhood Census had reported that kōhanga reo accounted for 9% of all licensed services with an additional number of 43 Māori immersion and bilingual early childhood services representing only 0.1% of all licensed ECE services in Aotearoa (Education Counts, 2024). This number had decreased by 12 in the year since the 2022 ECE census. Notably, kindergartens and home-based te reo Māori bilingual and immersion services had the highest proportion of Māori children enrolled (Education Counts, 2024). Whilst kindergartens are holding their own, other not-for-profit services such as Māori immersion and Pacific language nests are struggling to survive under the current policy and funding regime.

Figure 2 shows the domination of “education & care” sector in service types 2018–2023.

These Ministry of Education statistics signal that current policy is not delivering equitable access with regard to te reo Māori immersion settings. However, they are not transparent about the extent of privatisation of the early childhood sector. Michelle Duff’s (2023) reporting uncovered the extent of corporate capture of early childhood funding. Both Best Start and Evolve made $20 million profit. Although Best Start is registered as a “charity”, that $20 million profit was actually paid to the owners, the Wright Family Trust. There is a lack of the obligation for transparency in how these for-profit and “charity” services utilise their extensive government funding. Whilst the government purchases this private provision, it declines to require accountability as to how this funding is spent. As Linda Mitchell has noted, this means they can “maximise their profits by reducing staff numbers to the minimum required, employing cheaper unqualified staff and cutting back on employment conditions” (2019a, p. 31).

Figure 1: Number of enrolments/attendances in licensed services, by service type, 2004–2014 (Education Counts, 2015, p. 8)

Figure 2: Number of licensed early learning services by service type (Education Counts, 2025)

The current New Zealand Government regulatory review of the ECE sector follows the neoliberal playbook as outlined by Grace Blakeley (2024). She describes how neoliberal politicians aim to reduce governmental responsibility and expenditure for public infrastructure, facilitating exploitation by “free market” corporates. A key plank of their economic platform is seen when “on entering office they proceed to distribute public cash to private corporations” promulgating regulations that enrich vested interests, whilst ignoring and repressing all those who oppose this abrogation of social responsibility (Blakeley, 2024, p. 36). David Seymour, the ACT party politician directing the Early Childhood Education (ECE) Regulatory Sector Review (Ministry for Regulation, 2025), has made very clear the intention to treat ECE provisionas primarily profit-generating private businesses rather than as a public good, and therefore to support for-profit providers by reducing compliances such as ensuring fully qualified staffing and adherence to Te Whāriki, that would otherwise have contributed to quality care and education. (Dalli et al., 2025)

This is despite calls from many in the sector, and over many years, for government to fully fund high-quality ECCE provision via the not-for-profit community-based services such as kindergarten, kōhanga reo, Pacific language nests, and other community-based centres (Mitchell, 2019b, 2022; Neuwelt-Kearns & Ritchie, 2020). This has been effectively opposed by for-profit sector lobbyists, as highlighted in 2022, by Linda Mitchell. She concluded her paper strongly:

The benefits for children and families of good quality ECE are indisputable. The time is right for a transformative agenda that puts children’s interests first and moves ECE out of the private domain. Early childhood education should be an entitlement for all children, free to attend, and accessible to all families. It should be a public responsibility, publicly funded, employ well qualified and well remunerated teachers/kaiako who are paid as public servants on a national employment agreement, and be democratically accountable to the public in the same way as schools. (Mitchell, 2022, p. 143)

Such a shift, to position and fund ECCE alongside schools as a public good, would eliminate the corruption evident in the current situation and return the funds currently extracted by private and corporate profiteering to children, whānau, and communities. Instead, the current Government is expanding its privatisation drive into the school sector via soliciting new charter schools as well as by encouraging existing state schools to become charter schools. This is despite the fact that the earlier charter schools failed both aspirations of innovation and better achievement (Minstry of Education, 2019).2 Yet this current policy furthers the capacity for private businesses and international corporations to profit, with minimal accountability, from government funding which should instead be used to improve the state system.

Kindergartens Aotearoa commitments

This article draws from a presentation to representatives of Kindergartens Aotearoa (KA), a national collective of various regional kindergarten associations, working to address government policy to ensure that “public ECE services remain equitable, accessible, and responsive to the diverse needs of Aotearoa’s communities” (Kindergartens Aotearoa, 2025a, para. 2). KA was formed with the purpose of ensuring that kindergartens “remain a public, community-based, not-for-profit service [providing] high-quality early childhood education accessible to all tamariki and their whānau” (Kindergartens Aotearoa, 2025b, para. 1). The collective is further committed to “upholding Te Tiriti o Waitangi and fostering community partnerships [which] are central to our mission of delivering education that reflects and respects the diverse identities of Aotearoa’s people” (Kindergartens Aotearoa, 2025b, para. 2).

The aspiration is for kindergartens and other community-based, non-profit services to operate without costs for families, fully staffed by qualified teachers, and accessible to all families in all communities. Additionally, the commitment to equity and responsiveness to diverse needs acknowledges that all children and families have an equal right to wellbeing and education, but to achieve this we need to take account of historic and current inequities, that demand differential treatment as the remedy. Equity is therefore required in response to our histories of colonisation, whereby Māori have been systematically stripped of their land and language, the sources of identity, whakapapa, and their economic base. An equitable response means we have to prioritise the inclusion of te reo Māori within our early childhood provision, as a step towards restoration of what has been destroyed over generations. Delivering equity also requires provision that responds to the specificities of children and families, rather than a “one-size fits all”, “I treat all children the same” approach. This emphasises the importance of a fully qualified teacher workforce along with appropriate levels of additional staffing to ensure support for children who need extra support. It also involves affirming children’s diverse identities by authentically including their home and heritage languages and cultures.

Responding to diversity is a very contemporary imperative, since we now have a population that is categorised as “superdiverse” (Chan & Ritchie, 2023). Recent statistics show that Māori now represent 20% (1,036,000) of the total population (Stats NZ Tatauranga Aotearoa, 2025). Pacific Peoples comprise 8.8%. Furthermore, the 2018 national census found that almost 30% of New Zealanders were born overseas, representing 200 different countries and 150 languages. Only 4.3% of our total population can converse in te reo Māori (Stats NZ, Tatauranga Aotearoa, 2024). Superdiversity approaches recognise that complexities reach beyond ethnic, linguistic, and religious differences, requiring consideration of the overlapping multiple characteristics including “growing social and economic inequalities—disparities surrounding resources, opportunities, material outcomes, representation and relative social status” (Vertovec, 2022, p. 4).

Some teachers may find addressing these commitments challenging. Frustratingly, our schooling sector does not yet systematically foster bilingualism in te reo Māori. Therefore, the majority of both teacher education students and qualified teachers are likely to still be building their capacity to integrate te reo Māori and te ao Māori into their practice. Yet in doing so they are already moving away from a monocultural lens, a first step in broadening their pedagogical repertoire to include the languages, songs, and stories that both represent, celebrate, and affirm the identities and cultures of all children and their whānau in their local communities. A government that truly valued the current and future wellbeing of its youngest citizens would enact policies that supported the aspirations outlined above, rather than regulating to improve the profit margins of private and corporate businesses.

Notes

1I problematise this terminology by using speechmarks, since all early childhood services provide both care and education. Furthermore, the use of this catch-all phrase fails to distinguish between non-profit community-based services and those that are for-profit private and corporate businesses.

2Giles Dexter reported for Radio New Zealand how previous documents pertaining to charter schools were deliberately removed prior to the reintroduction of charter schools in 2024: https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/political/526757/out-of-date-charter-school-documents-removed-from-website-ahead-of-policy-announcement

References

Bakken, L., Brown, N., & Downing, B. (2017). Early childhood education: The long-term benefits. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 31(2), 255–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568543.2016.1273285

Bauchmüller, R., Gørtz, M., & Rasmussen, A. W. (2014). Long-run benefits from universal high-quality preschooling. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29(4), 457–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2014.05.009

Bishop, R., & Glynn, T. (1999). Culture counts: Changing power relations in education. Dunmore.

Blakeley, G. (2024). Vulture capitalism: Corporate crimes, backdoor bailouts, and the death of freedom. Atria Books.

Chan, A., & Ritchie, J. (2023). Exploring a Tiriti-based superdiversity paradigm within early childhood care and education in Aotearoa New Zealand. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 24(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1463949120971376

Dalli, C., Ritchie, J., & Mitchell, L. (2025). Cost cutting risks children’s learning and wellbeing. Early childhood education services are not and should never be considered merely a business proposition. Newsroom. https://newsroom.co.nz/2025/04/16/cost-cutting-risks-childrens-learning-and-wellbeing/

Duff, M. (2023). The jugglenaut: How childcare became a for-profit game. Stuff. https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/education/300814789/the-jugglenaut-how-childcare-became-a-forprofit-game

Education Counts. (2015). Annual ECE census report 2014. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/publications/ECE/annual-early-childhood-education-census/annual-early-childhood-census-2014

Education Counts. (2024). Annual ECE census 2023 fact sheets. Te reo Māori in early learning. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/publications/ECE/annual-early-childhood-education-census/annual-ece-census-2023-fact-sheets

Education Counts. (2025). Annual ECE census 2024: Fact sheets. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/publications/ECE/annual-early-childhood-education-census/annual-ece-census-2024-fact-sheets

García, J. L., Bennhoff, F. H., Leaf, D. E., & Heckman, J. J. (2021). The dynastic benefits of early childhood education. https://www.nber.org/papers/w29004

Kindergartens Aotearoa. (2025a). Kō wai mātou? https://kindergartensaotearoa.org.nz/about/

Kindergartens Aotearoa. (2025b). Why Kindergartens Aotearoa was established. https://kindergartensaotearoa.org.nz/kindergarten-movement/

May, H. (1992). Learning through play: Women, progressivism and early childhood education 1920s–1950s. In S. Middleton & A. Jones (Eds.), Women and education in Aotearoa 2 (pp. 83–101). Bridget Williams Books.

May, H. (2013). The discovery of early childhood (2nd ed.). NZCER Press.

May, H. (2015). Nineteenth century early childhood institutions in Aotearoa New Zealand: Legacies of enlightenment and colonisation. Journal of Pedagogy, 6(2), 21–39.

May, H. (2020). Politics in the playground: The world of early childhood education in Aotearoa New Zealand. Otago University Press.

May, H., & Bethell, K. (2017). Growing a kindergarten movement in Aotearoa New Zealand. Its people, purposes and politics. NZCER Press.

McCoy, D. C., Yoshikawa, H., Ziol-Guest, K. M., Duncan, G. J., Schindler, H. S., Magnuson, K., Yang, R., Koepp, A., & Shonkoff, J. P. (2017). Impacts of early childhood education on medium- and long-term educational outcomes. Educational Researcher, 46(8), 474–487. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X17737739

Ministry of Education. (1996). Te whāriki. He whāriki mātauranga mō ngā mokopuna o Aotearoa: Early childhood curriculum. Learning Media.

Ministry of Education. (2017). Te whāriki. He whāriki mātauranga mō ngā mokopuna o Aotearoa. Early childhood curriculum. Author. https://www.education.govt.nz/early-childhood/teaching-and-learning/te-whariki/

Minstry of Education. (2019). Charter schools close out report: Priority learners. [no longer available on Ministry of Education website]

Ministry for Regulation. (2025). Early childhood education (ECE) regulatory sector review. https://www.regulation.govt.nz/regulatory-reviews/early-childhood-education-ece-regulatory-sector-review/

Mitchell, L. (2002). Differences between community owned and privately owned early childhood education and care centres: A review of evidence. https://www.nzcer.org.nz/sites/default/files/downloads/11743.pdf

Mitchell, L. (2011). Enquiring teachers and democratic politics: Transformations in New Zealand’s early childhood education landscape. Early Years, 31(3), 217–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2011.588787

Mitchell, L. (2014). Alternatives to the market model. Reclaiming collective democracy in early childhood education and care. Early Education, 55(Autumn/Winter), 5–8.

Mitchell, L. (2019a). Democratic policies and practices in early childhood education. An Aotearoa New Zealand case study. Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-1793-4

Mitchell, L. (2019b). Turning the tide on private profit-focused provision in early childhood education. New Zealand Annual Review of Education, 24, 75–89. https://doi.org/10.26686/nzaroe.v24i0.6330

Mitchell, L. (2022). Transformative shifts in early childhood education systems after four decades of neoliberalism. New Zealand Annual Review of Education, 28, 132–147. https://doi.org/10.26686/nzaroe.v28.8592

Neuwelt-Kearns, C., & Ritchie, J. (2020). Investing in children? Privatisation and early childhood education in Aotearoa New Zealand. https://www.cpag.org.nz/publications/privatisation-and-early-childhood-education-in-aotearoa-new-zealand

NZEI Te Riu Roa. (2014). Submission to Productivity Commission inquiry into more effective social services. A case study on the provision of early childhood education. https://www.treasury.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2024-05/pc-inq-mess-sub-040-new-zealand-educational-institute-te-riu-roa.pdf

Shonkoff, J. P. (2017). Breakthrough impacts. What science tells us about supporting early childhood development. YC Young Children, 72(2), 8–16. https://www.jstor.org/stable/90004117

Skerrett, M. (2021). The shadows and silences of colonialism: Resisting eroding realities for Māori children through language re-vernacularisation in Antipodean New Zealand. In G. S. Cannella & T. A. Kinella (Eds.), Childhoods in more just worlds: An international handbook (pp. 55–70). Myers Education Press.

Stats NZ. Tatauranga Aotearoa. (2024). Census results reflect Aotearoa New Zealand’s diversity https://www.stats.govt.nz/news/census-results-reflect-aotearoa-new-zealands-diversity/

Stats NZ. Tatauranga Aotearoa. (2025). Aotearoa New Zealand’s population passes 5.3 million people. https://www.stats.govt.nz/news/aotearoa-new-zealands-population-passes-5-3-million-people/

Vertovec, S. (2022). Superdiversity: Migration and social complexity. Routledge. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203503577

Wylie, C., & Thompson, J. (2003). The long-term contribution of early childhood education to children’s performance. Evidence from New Zealand. International Journal of Early Years Education, 11(1), 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966976032000066109

Professor Jenny Ritchie teaches at Te Herenga Waka Victoria University of Wellington. Her experience includes being a childcare worker, kindergarten teacher, parent, Tiriti educator, kōhanga and kura whānau member, teacher educator, researcher, and grandparent. She focuses on education for social, cultural, ecological and climate justice.

Email: jenny.ritchie@vuw.ac.nz