Early childhood education as a public good

Challenges and possibilities

Linda Mitchell, Vida Botes, and Olivera Kamenarac

This article is premised on a view that early childhood education (ECE) is a public good and a child’s right. As such, there is no place for ECE services to be treated as a private commodity that is bought and sold in the marketplace. Yet, despite policies to transform its ECE system under some enlightened governments, no substantive attempts have been made to shift from a model of marketisation and privatisation in providing ECE. This article discusses recent research on the growth of publicly listed companies in the ECE sector and consequences, whereby financial values and profit-making are prioritised over education values. ECE services have come to be understood as businesses, competing and selling commodities (“childcare” and “learning”) to parent and child “consumers”. Effects of corporatisation in Aotearoa New Zealand are then exemplified through the authors’ recent research comparing a large kindergarten association with a similar-sized publicly listed ECE company. Differences in the composition of their boards (diversity of ethnicity, gender, age, and representation of parents, staff, and specialists), Education Review Office ratings of services, and payments made to directors are analysed. The article ends by suggesting possibilities for de-privatising ECE in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Introduction

This article is premised on a view that high-quality early childhood education (ECE) is a public good that benefits children, parents, whānau, and society and is a right for all children that is free of charge. As such, it should be provided and planned in partnership with the government with the full funding from public resources going into educating the child and supporting the family. These ideals were encapsulated in a report by the Quality Public Early Childhood Education Project (May & Mitchell, 2009), a coalition of national ECE organisations that, in 2009, developed a shared vision for strengthening community-based ECE in Aotearoa New Zealand. The vision is embedded in images of the child and the whānau that are articulated in Aotearoa New Zealand’s national curricula.

Te Whāriki, ECE Curriculum (Ministry of Education, 2017b, p. 5) upholds a vision for children as “Competent and confident learners and communicators, healthy in mind, body and spirit, secure in their sense of belonging and in the knowledge that they make a valued contribution to society”. The overriding principle of mana from Te Whāriki a Te Kōhanga Reo (Ministry of Education, 2017a) offers aspirational images of the young child and all who participate in kōhanga reo. Reedy (2013) describes mana as “the enabling and empowering tool that supports children to control their destiny” (p. 47). Te Tiriti o Waitangi, signed in 1840, is the constitutional foundation of Aotearoa New Zealand and underpins the ECE curriculum. “This agreement provided the foundation upon which Māori and Pākehā would build their relationship as citizens of Aotearoa New Zealand. Central to this relationship was a commitment to live together in a spirit of partnership and the acceptance of obligations for participation and protection” (Ministry of Education, 2017b, p. 3). These images and commitments offer a foundation for ECE policy and practice in Aotearoa New Zealand.

This article describes the current Aotearoa New Zealand context including recent ECE policy announcements, and the neoliberal reliance on marketisation, competition, and privatisation for provision of education and care and homebased services. International research is highlighted showing negative impacts of these features and ways in which they prioritise financial values and shape conceptualisations of ECE services as businesses, parents and children as consumers, and staff as dispensable workers. New research is presented that compares the use of funding, composition of boards, and Education Review Office (ERO) ratings in a large for-profit ECE company with a similar-sized kindergarten association in Aotearoa New Zealand. The article ends by discussing possibilities to influence the ECE policy agenda in Aotearoa New Zealand towards systemic change.

The Aotearoa New Zealand context, marketisation, and recent ECE policy announcements

When the current coalition Government was elected in October 2023, Aotearoa New Zealand had made some steps towards supporting ECE as a public good. Progress included the integration of childcare and education within an education ministry in 1986, and the values embedded within its ECE and kōhanga reo curricula (Ministry of Education, 2017a, 2017b). Steps had been made towards a 100% ECE-qualified workforce in teacher-led services and as co-ordinators in homebased services, but variations in the percentage of qualified teachers existed in education and care centres with some operating at the minimum standard of 50% qualified teachers. While parity of kindergarten teachers’ pay with the pay of primary teachers had been achieved, only limited progress had been made towards pay parity for teachers in education and care centres. The “20 hours ECE” policy had gone some way to making ECE free for 3- and 4-year-olds but there was no entitlement to a free place in a suitable ECE service. In recognition of the rights of children to access high-quality ECE, some countries have legislated to require free ECE provision to be available for all children. For example, in Sweden, municipalities are required by the Education Act to provide publicly subsidised preschool provision to all children from 12 months of age. All children are entitled to free preschool for at least 525 hours per year (approximately 15 hours per week) from the autumn term when they turn 3 years old (Eurydice, 2023). Moss and Mitchell (2024, pp. 187–192) discuss these aspects in greater depth.

Highly problematic over decades has been the reliance on a market approach to provision of ECE, and the lack of required accountability for spending government funding and lack of restrictions on levels of fees that could be charged. This approach has led to a burgeoning growth of private education and care and homebased services and contributed to the longstanding issue of oversupply in some communities and undersupply in others, particularly low socioeconomic and rural communities (May & Mitchell, 2009; Mitchell & Meagher-Lundberg, 2017). Some children are missing out on ECE and some services are very low quality. Fees charged are variable. A network management approach that might have enabled ECE provision to be planned and reduced some of the problems of allowing the market to determine ECE provision was adopted in 2022 under the previous Government. However, this was soon scrapped when a new coalition Government was elected in October 2023.

Under the coalition Government, influenced particularly by the ACT Party’s ideology, democracy is under attack. Emeritus Professor Anne Salmond called what is happening now in democracy “a blitzkrieg of bills”—the Fast-track Approvals Bill, the Treaty Principles Bill, the Regulatory Standards Bill. She wrote: “All involve constitutional overreach; the overuse of urgency in Parliament and other efforts to curtail democratic scrutiny” (Salmond, 2025, n.p.).

Through the ECE Regulatory Review (Ministry for Regulation, 2024) the gains won for ECE from literally decades of advocacy are being weakened and lost. In an open letter to politicians and background paper, a group of nine leading ECE academics and researchers explained:

The Review of ECE Regulations frames the provision of early childhood care and education in terms of free market provision, rather than recognising its foundational role as a core public good that, like schools, is a key government responsibility, and should be funded and regulated to ensure high quality. The market approach of the Review positions early childhood care and education as an industry and sector that relies on private and corporate ownership along with individual parental choice to determine access. (Dalli et al., 2024, p. 1)

The Review portrays ECE regulations as harmful restraints on the market. Governmental responsibility for quality would be weakened by the Review recommendations. Critical regulations requiring teachers to hold ECE qualifications are reduced in favour of making qualification requirements more flexible, particularly for services in rural and lower socioeconomic areas, Māori and Pasifika services, and homebased services. Licensing requirements related to curriculum standards are removed from legislation to a guidance document. This change would provide little to no accountability for the quality of experiences for children and families in ECE. The special status and rights of Māori as tangata whenua and Te Tiriti o Waitangi are questioned.

In the 22 May 2025 Government Budget, ECE received a minuscule 0.5% funding increase, equivalent to a cut because it did not keep up with inflation. Later in May, Associate Minister of Education David Seymour announced that education and care service employers would no longer have to pay new teachers parity rates (Ministry of Education, 2025) or take into account new teachers’ qualifications and experience. In a question in the House to justify the policy, Prime Minister Christopher Luxon set out his image of ECE as a business, of families and children as “consumers”, and of teachers as “workers” whose specialist qualifications were not relevant (and who could therefore be exploited by entrepreneur owners wanting to save on labour costs).

… we don’t believe that just because you’ve got a qualification … you should be paid more and be mandated to pay more than someone who’s got 25 years’ experience in ECE. That’s up to owners to work out what to pay their workers so they can work out what they charge to their consumers … That is normal business practice. (Hansard, 3 June 2025)

This position of a male leader reinforces the already existing inequalities and gender gap in society since ECE is a predominantly female-led profession. The NZEI Te Riu Roa website links issues of pay equity to “the historical undervaluing in both pay and status in roles that society has perceived to be ‘women’s work’” (NZEI Te Riu Roa, 17 August, 2023).

Impacts of marketisation and the growth of private provision, private equity, and investment companies

Marketisation and privatisation conceptualise ECE services as businesses, and parents and children as consumers, as Prime Minister Christopher Luxon conveyed. They prioritise financial values; these are incompatible with valuing ECE as a public good, an institution in civil society.

Community-based and private ECE services are differentiated by the Ministry of Education (Ministry of Education, 2024a) according to ownership and how financial gains can be used. An ECE service that is community-based is prohibited from making financial gains that are distributed to their members. They include an incorporated society, a charitable, statutory, or community trust, a registered charity, owned by a community organisation (e.g., a city council, church, or university), and considered a Public Benefit Entity under XRB requirements. All state kindergartens, kōhanga reo, playcentres, and playgroups are community-based. A private ECE service is able to make financial gains and distribute these to their members. It may be owned by a private company, publicly listed company, private trust, partnership, or an individual. Private provision is found in education and care centres and homebased services.

In the past three decades, private education and care centres and homebased services have increased markedly, to the extent that, in 2024, 65% and 90% respectively were privately owned, up from 54% and 36% respectively in 2002 (Ministry of Education, 2024b). More children attend private ECE services. Private ECE services provide 69% of the total 214,062 licensed places in the whole of the ECE sector (teacher-led and parent/whānau-led) (Ministry of Education, 2024c).

International businesses have recently bought ECE services in Aotearoa New Zealand. Their commentary around their sales and “acquisitions” is about ECE as a business proposition that generates profits for shareholders and/or companies. The rationale for owning ECE services is far removed from conceptions of ECE as a public good.

Evolve Education Group currently owns 90 education and care centres and is the second largest provider of education and care centres in Aotearoa New Zealand. In September 2022, Evolve Education Group sold what it called its “portfolio of early childhood education and care centres” to Anchorage Capital Partners, an Australasian private equity firm for a value of around NZ$46 million, providing Evolve with a “cash-rich balance sheet”. Excerpts from the board chair to the special meeting of shareholders to ratify the sale conceptualise ECE as a private commodity, marketised and framed in economic terminologies. Cost benefits and high returns on investment for shareholders are the main considerations. The Australian market was portrayed as being much more attractive than the New Zealand market, which had been impacted by closures during Covid.

The directors of Evolve are proposing a significant strategic realignment of the company. In essence a reallocation of physical, financial, and management resources to the Australian market—a market with stronger attractive attributes and which we believe will provide Evolve shareholders with substantially higher long term returns. (Evolve Education Group, 2022, p. 2)

Busy Bees Childcare, the UK’s largest ECE provider, announced its first “acquisition” of 75 ECE centres (more than 5,500 places) in Aotearoa New Zealand from New Zealand-based group Provincial Education in 2021. Busy Bees is majority owned by Canada’s Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan and “grew from 230 nurseries in the UK to 910 across 10 countries, including Singapore, Australia and Canada” (Ontario Teachers Pension Plan, 2022). Busy Bees is now the third largest provider of education and care centres in Aotearoa New Zealand. A significant amount of money (from government funding and parent fees) is needed for debt repayment. Moss and Mitchell (2024, pp. 48–51) discuss the rapid expansion of Busy Bees across the rich world, the money owed to its parent company and banks (£790 million in December 2022), and its “mounting backlog of interest payments” (Moss & Mitchell, 2024, p. 50). The United Workers Union (United Workers Union, 2022) recently exposed financial practices of for-profit providers in Australia, that included Busy Bees, as paying exorbitant salaries to owners and executives and avoiding tax by paying the parent company offshore and registering a debt.

These “acquisitions” place a sizeable number of ECE centres in the hands of international financialised companies whereby making profits has become a powerful and dominant reason for providing ECE. These practices erode the concept of education as a public good (Carney, 2020) by favouring for-profit and enterprise interests over the learning and wellbeing of children. Recent research by The Guardian and the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (Garcia & Stewart, 2024) analysed the accounts of the 43 largest childcare providers in England. It showed nurseries backed by private investment companies (including private equity firms, asset managers, and international pension funds) reported double the profits of private providers not backed by investment companies and seven times the profits of non-profit providers.

Another English study (Simon et al., 2022) examined how public funding given to the private nursery sector was used, differences in use of funding and provision between public and private sectors, and the location of provision in relation to deprivation. It found staff costs were 14% lower in the for-profit companies compared with the not-for-profit group. Not-for-profit organisations used parents and staff on their boards of trustees to represent the needs of families and support their staff; corporate companies did not. For-profit childcare companies used foreign investors and shareholders, alongside public money, to expand their “market share” but, while shareholders and their senior executives profited from investing in these companies, little of the money was being reinvested back into the sector. Private-for-profit companies were expanding through acquiring existing services—they had not contributed to a growth of places for children. The research found “market dynamics can lead to insufficient coverage in poorer, less profitable areas” (UCL News, 2022).

Staffing is the largest cost item in providing ECE, and profits can be made by reducing these costs. Similar to the findings from the UCL English study, an Australian study (United Workers Union, 2022, p. 8) found “the not-for-profit providers devote 70–80 per cent of revenue to employees, while the share in the commercial sector is as low as 54 per cent”.

Stienon and Boteach (2024) offer an explanation of common private equity tactics that include:

•using debt to acquire new portfolios so that loan repayments need to be made. These loan repayments divert from spending on other important expenses, such as staffing

•roll-ups and mergers whereby larger companies push out smaller “competitors”

•control over management and operations, guided by fund priorities. “In many cases new managers are empowered to do whatever it takes to maximise profits, even at the expense of the long-term health of the company, and that of its employees, customers, and suppliers” (p. 6).

Using research evidence from ageing and disability care, hospice care, and physicians’ practice in the US, they illustrate that “private equity-owned businesses are more likely to push down the quality of services they provide, the wellbeing of their customers and workers, and the competitive health of local markets” (p. 5).

In Aotearoa New Zealand, the community-based ECE sector is up against private equity firms and investment brokers that reduce the main purpose of ECE to investment opportunities. For-profit ECE centres receive the same government funding as non-profit and community-based ECE services. They receive the government funding subsidy based on the staffing profile, and number and ages of children attending. They are eligible for government grants towards the cost of new buildings and building extensions. Centres built from these government funds are then owned by the company. Additionally, there are no limits on the parent fees that can be charged.

Several studies have shown that for-profit ECE provision compared with community-based provision is rated lower on indicators of quality. For-profit provision provides poorer staff working conditions and pay, employs lower percentages of qualified teachers, and offers more restricted access than community-based and public provision (Friendly et al., 2021; Lloyd & Penn, 2012).

Evolve Education Group compared with Whānau Manaaki Kindergartens

A small study carried out in 2021 by the authors investigated and compared the governance, use of funding, social and business values, and ERO ratings of Evolve Education Group and Whānau Manaaki Kindergartens. The two ECE organisations were chosen because they were of similar size and had different governance and ownership structures. At the time of the research, Evolve owned 111 education and care centres in Aotearoa New Zealand and had just sold its “portfolio of early childhood education and care centres” to private equity company Anchorage Capital Partners in Australia for a value of around $46 million. In 2021, Whānau Manaaki Kindergartens had 103 kindergartens. It is an incorporated society.

Evolve, as a listed company, submitted its financial reports to the New Zealand Stock Exchange while Whānau Manaaki Kindergartens submitted its financial statement to the Charities Commission. We used a case study approach as it allowed us to look at the organisations in greater detail (Siggelkow, 2007). We examined governance, profitability, and performance over several years. We examined the annual audited reports over 4 years, their ownership structures, levels of borrowing, and debt. Owing to well documented issues of staff shortages and low wages in the sector, we also examined financial ratios related to these issues. This helped us to understand the proportion of company income spent on staff costs as well as trends.

The overall judgement from the most recent ERO report for each centre or kindergarten in the respective organisations was recorded. ERO used one of four classifications in 2021 to judge how well the service promotes positive learning outcomes for all children. The categories were:

•Very well placed

•Well placed

•Requires further development

•Not well placed.

A two-tailed t-test was used to analyse significance of difference between the ratings.

Board structures and payments to members

The economic imperatives driving Evolve were reflected in the gendered, ethnically homogeneous, and business-oriented backgrounds of the board and the payments made to board members. The background of the independent directors in the 2021 Evolve Annual Report showed strong acumen in business (manufacturing), law, and finance and investment banking. Both the non-independent directors’ experience in ECE came from either driving or consulting on the listing of the largest listed early childcare provider in Australia. Despite strong recommendations in the NZX Corporate Governance Guidelines (2019) to have increased diversity on the board as it is associated with improved financial performance, there were no female representatives. Directors are elected by the shareholders of Evolve to serve on the board. Shareholders are entitled to vote according to the number of shares they hold. The board consisted of three independent shareholders and two non-independent shareholders. Independent shareholders are usually appointed based on skills that they bring to the board and do not hold shares in Evolve. Non-independent shareholders are people who have a financial interest in the form of shares in the organisation. In this case, the insiders (those with financial interest in Evolve) held 23% of the total shares. Board payments in Evolve totalled $475,000 for five directors which averaged $95,000 per annum. Timothy Wong resigned as Evolve CEO on 30 March 2021. He received 1.25 million share options exercisable at AU$1.20 per share which expired on 31 December 2023. (Nothing had been exercised by 31 December 2021.) The Board of Directors is usually involved in appointing the management of the organisation. In the case of Evolve, the management team consisted of seven people, of whom two were female. One of the directors, Chris Scott who holds shares in Evolve, is also the managing director (Evolve Education Group, 2021).

Whānau Manaaki Kindergartens operated as a democratic organisation, with board structures that extended power and responsibility to elected members representative of those who use, teach in, and support kindergarten communities. In 2021, the board of Whānau Manaaki Kindergartens consisted of nine members (two men and seven women). Two of these were Māori, one Pacific, five were Pākehā New Zealanders, and one Polish/Australian. The board is elected by the membership at the Annual General Meeting each year. Six members were elected by the community, two were staff representatives, and one was board-appointed. Ages ranged from 35 to 55 years. The board delegates day-to-day management of Whānau Manaaki to the chief executive (Whānau Manaaki Kindergartens, 2025b). Hence, there was greater gender, ethnic, and age diversity on the board which included a female chief executive. The structure makes Whānau Manaaki Kindergartens accountable to the wide constituency and the social justice and democratic aims that were evident in its vision statement (Whānau Manaaki Kindergartens, 2025a). The board payments for Whānau Manaaki totalled $40,000, or an average of between $4,000 and $5,000 per board member.

Percentage of total revenue spent on staffing

In 2021, Evolve spent 62% of total revenue on staffing, compared with 91% spent by Whānau Manaaki Kindergartens. This spending differential is similar to that found between for-profit companies and not-for-profit organisations in the English and Australian studies cited above (Simon et al., 2022; United Workers Union, 2022).

ECE staff are crucial in ensuring high-quality ECE environments that enhance children’s learning and development.

Forty years of research evidence, across multiple jurisdictions … identifies qualified staff as one of three policy variables—together with appropriate adult–child ratios by age, and group size—that form the ‘iron triangle’ of quality (Ruopp et al., 1979). The variables impact both adult and child behaviour, with fewer positive interactions and less advancement in development associated with lower staff qualifications and larger group sizes. (Dalli et al., 2024, p. 3)

The percentage of revenue that companies and organisations spend on staffing is an indicator of their values. Spending on staffing is prioritised in Whānau Manaaki Kindergartens in comparison with Evolve.

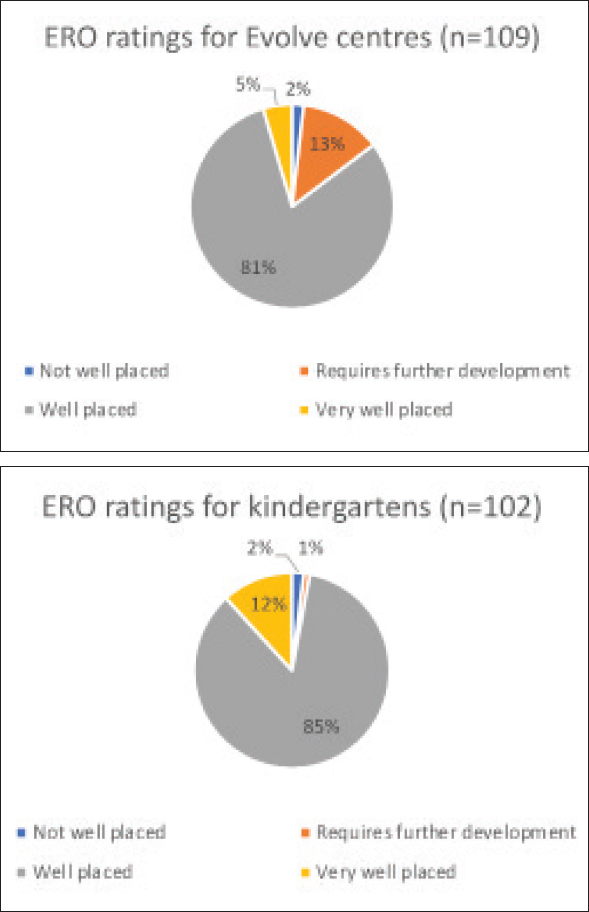

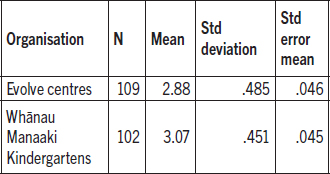

Education Review Office ratings

Differences between the extremes in ERO ratings for Whānau Manaaki Kindergartens and for Evolve ratings are apparent. While 1% of kindergartens (one) had a rating of “Not well placed”, 13% of Evolve centres (14) had this rating. A higher percentage (12%) of kindergartens had a rating of “Very well placed”, compared with only 5% of Evolve centres.

Figure 1. Comparison of ERO ratings for Evolve centres and Whānau Manaaki Kindergartens

Whānau Manaaki Kindergartens had higher mean scores for ERO ratings compared with Evolve centres. On average, their kindergartens were judged to be well placed to promote positive learning outcomes for all children. On average, Evolve centres were judged to be requiring further development to promote positive learning outcomes for all children.

Table 1. Mean ERO ratings for Evolve centres and Whānau Manaaki Kindergartens

Using a two-tailed t-test, statistically significant differences (p < 0.04) were found between these mean ERO scores, indicating an association between the ERO ratings and the organisations.

Towards ECE as a public good—influencing the policy agenda

The benefits for children and families of high-quality ECE are indisputable. Research over decades and in different countries shows that for-profit ownership and, in particular, financialised ECE provided by corporations, is associated with poorer structural and process quality (Friendly et al., 2021). Children as rights bearers (United Nations, 1989) have the right to access high-quality ECE that enhances their learning and wellbeing and supports their family. Aotearoa New Zealand’s system currently does not ensure this access as we have evidenced.

An urgent need is for a transformative agenda that puts children’s interests first and moves ECE out of the private domain. The recent book, The Decommodification of Early Childhood Education and Care. Resisting Neoliberalism (Vandenbroeck et al., 2023) explored how, through processes of marketisation and privatisation, ECE has become a commodity whereby economic principles of competition and choice have replaced the purpose of ECE. Written with co-authors of diverse countries, the book examined resistance to the commodification of children as human capital, parents as consumers, and alienation of the workforce. The acts of resistance were carried out by individuals and collectively through organised networks, associations, and unions. Examples from Aotearoa New Zealand (Kamenarac et al., 2023) included individual “micro-resistance” by a teacher employed in an ECE centre owned by one of the largest ECE business companies against the company’s financial priorities to support free attendance for families who could not afford ECE; a teacher working through multimodal means to ensure every child had a voice; and collective resistance through the teachers’ union to achieve parity of pay for early childhood teachers with pay of primary teachers. In summary, these authors argued:

Taken together, the examples reinforce that to combat neoliberal ECE policies and practices, ECE staff individually and collectively need to see themselves as ethically obliged and persistently committed to contributing to the vision of ECE as a universal right of a child … Finally, while giving the hope that combating neoliberalism is to some extent possible in some ECE spaces and places, a broader need is for the government to take responsibility for legislating and financing ECE services to establish a democratic, socially just and equitable ECE system for all children and families no matter their circumstances. (Kamenarac et al., 2023, p. 194)

ECE should be an entitlement for all children, free to attend, and accessible to all families. It should be a public responsibility, publicly funded, employ well qualified and well remunerated teachers/kaiako who are paid as public servants on a national employment agreement, and be democratically accountable to the public in the same way as schools.

References

Carney, M. (2020). The Reith lectures. How we get what we value. https://downloads.bbc.co.uk/radio4/reith2020/Reith_2020_Lecture_1_transcript.pdf

Dalli, C., Gunn, A., Kahuroa, R., Matapo, J., May, H., Mitchell, L., . . . Ritchie, J. (2024). Open letter to Prime Minister and Cabinet: ECE Regulatory Review background document to support letter to Prime Minister and Cabinet: ECE Regulatory Review Authors.

Eurydice. (2023). Sweden. Early childhood education and care. Access. https://eurydice.eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-education-systems/sweden/access

Evolve Education Group. (2022). EVO chair address. Special shareholders meeting 15 September 2022. https://www.evolveeducation.co.nz/media/12697/special-meeting-chair-s-address.pdf

Evolve Education Group. (2021). Full year results investor presentation. https://www.evolveeducation.co.nz/media/11919/full-year-results.pdf

Friendly, M., Vickerson, R., Mohamed, S. S., Rothman, L., & Nguyen, N. T. (2021). Risky business: Child care ownership in Canada past, present and future. https://childcarecanada.org/sites/default/files/Risky-business-child-care-ownership-in-Canada-past-present-future_1.pdf

Garcia, C. A., & Stewart, H. (2024, 12 March). Revealed: The bumper profits taken by English private nursery chains. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/money/2024/mar/12/private-nursery-chains-profits-england

Hansard. (2025, 3 June). Question No. 2—Prime Minister. https://www.parliament.nz/en/pb/hansard-debates/rhr/document/HansS_20250603_050700000/2-question-no-2-prime-minister/#:~:text=Rt%20Hon%20Chris%20Hipkins:%20Why,they%20charge%20to%20their%20consumers

Kamenarac, O., Kahuroa, R., & Mitchell, L. (2023). Stories of advocay and activism from within the New Zealand ECE sector. In M. Vandenbroeck, J. Lehrer, & L. Mitchell (Eds.), The decommodification of early childhood education and care. Resisting neoliberalism (pp. 186–194). Routledge.

Lloyd, E., & Penn, H. (Eds.). (2012). Childcare markets: Can they deliver an equitable service. The Policy Press.

May, H., & Mitchell, L. (2009). Strengthening community-based early childhood education in Aotearoa New Zealand. http://www.nzare.org.nz/portals/306/images/Files/May%20and%20Mitchell%20(2009)%20Report_QPECE_project.pdf

Ministry for Regulation. (2024). Regulatory review of early childhood education—full report. https://www.regulation.govt.nz/about-us/our-publications/regulatory-review-of-early-childhood-education-full-report/

Ministry of Education. (2017a). Te whāriki a te kōhanga reo. https://www.kohanga.ac.nz/kaupapa/te-whariki-a-te-kohanga-reo

Ministry of Education. (2017b). Te whāriki. He whāriki mātauranga mō ngā mokopuna o Aotearoa early childhood curriculum. https://tewhariki.tahurangi.education.govt.nz/early-childhood-curriculum-home

Ministry of Education. (2024a, 23 September). Glossary. https://www.education.govt.nz/education-professionals/early-learning/funding-and-financials/ece-funding-handbook/glossary

Ministry of Education. (2024b). Pivot table: Number of ECE services (2002–2024). https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/statistics/services

Ministry of Education. (2024c). Pivot table: Number of licensed ECE places (2000–2024). https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/statistics/services

Ministry of Education. (2025, 29 May). ECE updates. Changes to funding conditions of ECE pay parity scheme from 1 July. He Pānui Kōhungahunga. Early Learning Bulletin. https://www.education.govt.nz/bulletins/early-learning/29-05-25

Mitchell, L., & Meagher-Lundberg, P. (2017). Brokering to support participation of disadvantaged families in early childhood education. British Educational Research Journal, 43(5) 952-96. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3296

Moss, P., & Mitchell, L. (2024). Early childhood in the Anglosphere. Systemic failings and transformative possibilities. UCL Press.

NZEI Te Riu Roa. (2023, 17 August). Pay equity funding decision angers early childhood teachers. https://www.nzeiteriuroa.org.nz/about-us/media-releases/pay-equity-funding-decision-angers-early-childhood-teachers

Ontario Teachers Pension Plan. (2022). Busy Bees nurseries. Partnering in global growth. https://www.otpp.com/en-ca/about-us/news-and-insights/portfolio-insights/busy-bees-nurseries-partnering-in-global-growth/

Reedy, T. (2013). Tōku rangatiratanga nā te mana mātauranga: “Knowledge and power set me free . . .” In A. C. Gunn & J. Nuttall (Eds.), Weaving te whāriki, Aotearoa New Zealand’s early childhood curriculum document in theory and practice (2nd ed., pp. 35–9). NZCER Press.

Ruopp, R., Travers, J., Glantz, F., & Coelen, C. (1979). Associates: Final report of the National Day Care Study. Abt Associates.

Salmond, A. (2025). Hayek’s bastards. https://newsroom.co.nz/2025/01/21/anne-salmond-hayeks-bastards/

Siggelkow, N. (2007). Persuasion with case studies. Academy of management journal, 50(1), 20–24.

Simon, A., Penn, H., Shah, A., Owen, C., Lloyd, E., Hollingworth, K., & Quy, K. (2022). Acquisitions, mergers and debt: The new language of childcare—main report. UCL Social Research Institute, University College London.

Stienon, A., & Boteach, M. (2024). Children before profits. Constraining private equity profiteering to advance child care as a public good. https://nwlc.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Children-Before-Profits-Exec-Summary-WEB.pdf

UCL News. (2022, 27 January). Nursery sector risks being damaged by large corporate takeover. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/news/2022/jan/nursery-sector-risks-being-damaged-large-corporate-takeovers

United Nations. (1989). Convention on the rights of the child. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-child

United Workers Union. (2022). Spitting off cash. Where does all the money go in Australia’s early learning sector? https://unitedworkers.org.au/research/where-does-all-the-money-go-in-early-learning-sector/

Vandenbroeck, M., Lehrer, J., & Mitchell, L. (2023). The decommodification of early childhood education and care. Resisting neoliberalism. Routledge.

Whānau Manaaki Kindergartens. (2025a). Mo tātou uara | Our values. https://wmkindergartens.org.nz/about-us/our-values

Whānau Manaaki Kindergartens. (2025b). Te poari | The board. https://wmkindergartens.org.nz/about-us/the-board

Linda Mitchell is retired professor and honorary fellow, University of Waikato. She has spent many years researching early childhood education policy and practice, critiquing the marketisation and privatisation of early childhood education, and advocating for policy change.

Email: linda.mitchell@waikato.ac.nz

Vida Botes is a senior lecturer at the University of Waikato and Fellow Chartered Accountant (NZ). Vida’s research focuses on accounting developments, with a strong emphasis on forensic accounting and the effects of fraud in business.

Olivera Kamenarac is a senior lecturer in Education at Southern Cross University (Gold Coast Campus), Queensland. Olivera critically explores education as a contested space where power, policy, and politics intertwine with transformative potential.