A collaborative approach to transitions in Dannevirke

Lisa Bond, Jo Brown, Jenna Hutchings, and Sally Peters

In this article we present some initial findings from a Teacher-led Innovation Fund study undertaken in a kāhui ako based in the small community of Dannevirke. Teachers from the eight early childhood education (ECE) services and six schools have worked together to explore teacher practice and research the impact of teacher pedagogy on the transition, wellbeing, and academic engagement of tamariki in their community. The findings demonstrate that while, initially, there was little understanding or use of the other sector’s curriculum, teachers have been sharing their knowledge and expertise across sectors, leading to deeper understandings of children’s learning and the links between curricula. Using knowledge gained, each setting has been working on its own goals. Two trends in these goals have been to enhance the confidence and independence of tamariki in ECE and offering play-based pedagogies in the new entrant classrooms. The study shows the power of teachers working across sectors and the possibilities when teachers come together to work for the benefit of tamariki across their whole community.

Introduction

The role of teachers working across sectors to support children’s transition to school has been a key focus nationally and internationally. For example, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Starting Strong V report indicated that “quality transitions should be well-prepared and child-centred, managed by trained staff collaborating with one another, and guided by an appropriate and aligned curriculum” (OECD, 2017, p. 1). New Zealand’s draft Strategic Plan for Early Learning 2019–29 noted that collaboration between early childhood education (ECE) services, schools, and kura supports positive transitions and can also ensure greater understanding about how the national curricula complement each other (Kōrero Mātauranga, 2018, p. 41). Kōrero Mātauranga (2018) also highlighted that when children experience “good transitions” within ECE and to school or kura this is one aspect of meeting the goals for quality.

The New Zealand ECE curriculum Te Whāriki (Ministry of Education, 2017) makes links to school within each of its principles. It also includes a detailed section on Pathways to School and Kura that highlights the value of teachers in ECE and school working together “to support children’s continuity as they make this crucial transition” (Ministry of Education, 2017, p. 51). Tables in the Pathways section make specific links between the learning outcomes of Te Whāriki and the school curriculum documents, The New Zealand Curriculum (Ministry of Education, 2007) (NZC) and Te Marautanga o Aotearoa (Ministry of Education, 2008). Similarly, a principle of NZC is coherence, and includes the expectation that the curriculum “provides for coherent transitions and opens up pathways to future learning” (p. 9).

Both Te Whāriki and NZC draw attention to the child’s holistic experience. Holistic development / kotahitanga is a principle of Te Whāriki and taking account of “the child’s whole experience of school” forms part of the transitions information in NZC (p. 41). In line with this holistic focus, there is strong support in the literature for taking account of children’s wellbeing and engagement as part of a successful transition to school (see Peters, 2010), and the OECD (2017) report noted the impacts for children’s wellbeing and learning outcomes where teachers created alignment and coherence between sectors leading to less-disruptive transitions.

A recommendation from the New Zealand Education Review Office (ERO) (2015), based on research into how well early childhood services and schools were supporting children’s transitions, was for early childhood services and schools to:

•review the extent to which their curriculum and associated assessment practices support all children to experience a successful transition to school

•establish relationships with local schools and services to promote community-wide understanding and sharing of good practice (ERO, 2015, p. 3).

This article presents some initial findings from a Teacher-led Innovation Fund (TLIF) project, based in Dannevirke, where as a community we want to explore how to enact these intentions.

Background to the project

Historically, the Dannevirke ECE teachers and new entrant teachers have had some attempts at working together around transition. In 2006, early learning services and new entrant classroom teachers worked together on a project that focused on literacy and transition to school practices. The Massey University Centre for Educational Development was contracted by the Dannevirke Joint Schools Initiative Funding project (JSIF) reference group to gather information about transition to school and literacy practice in ECE settings and new entrant/Year 1 classes in the Dannevirke area.

When this project was completed there was no further work, and relationships diminished. In more recent years, Tararua Rural Education Activities Programme [REAP] began a network group for ECE and new entrant teachers. This formed the basis for the beginning of meaningful relationships between sectors.

The Dannevirke Kāhui Ako was formed in 2016. An achievement challenge based around National Standards was approved, and official work began in 2017. The Dannevirke Kāhui Ako was one of the first within New Zealand to ensure that ECE services were part of the team. The kāhui ako welcomed ECE into the group, and an ECE representative was appointed to the management group by the early childhood sector.

As a kāhui ako, it was decided there were four important strands to work on to potentially raise the achievement of tamariki within the community. These focuses were Pedagogy and Teaching as Inquiry, Engagement and Cultural Responsiveness, Assessment, and Transitions.

When looking into the transition process that ECE services and new entrant teachers followed there was huge variation across the community. As a group, it was decided that it would enhance the transition for tamariki if there was a consistent approach. As a team of teachers we used both ECE and school curricula to create a list of information that would be beneficial for teachers to share across sectors about tamariki transitioning to school. We used the “Pathways to School and Kura” section of Te Whāriki (Ministry of Education, 2017) to begin to explore the connection between the strands in Te Whāriki and the key competencies and learning areas in NZC.

Once this information was gathered, it was placed into a transition document that all early childhood services would send to school before the tamariki started. Through the discussions and work this team of teachers underwent it was apparent that each sector had little to no understanding of each other’s curriculum and more work would be needed before we could put our transition goals into action. There was a burning desire to continue building relationships and knowledge across the sector, and the decision was made to put a TLIF research proposal together around transition to school. This would provide the platform and financial ability for the ECE sector and new entrant teachers to work together with a focus on positive outcomes for the tamariki of Dannevirke. An inquiry question was established and funding approved by the Ministry of Education’s TLIF.

Having the children of Dannevirke see that the teachers who care for them have a vested interest in their future is something we strive for. As a kāhui ako we wanted to create an effective transition process across our learning community. We know from our own experience and from reading literature (see, for example, Education Review Office, 2015; Ministry of Education, 2017; Peters, 2010) that relationship building is paramount for developing effective transition pathways. As a small community we are exploring the possibilities for children when all ECE services and schools work together to enhance transitions.

We are committed to supporting positive transitions for tamariki and their whānau. Our innovation is to explore how to build the knowledge and capabilities of our teachers. We are researching both this process and the impact that a change in teacher practice makes for children’s learning. ERO (2015) found that, where teachers and leaders understood the links between ECE and school curricula, they were able to provide a curriculum that was meaningful for tamariki. We want to explore how that knowledge can be developed and, having the knowledge of the two curricula, how there can be a pedagogical shift that benefits children. The innovation is looking at current practices, what the teachers could change, and what new things they could incorporate. In this article we share some of our initial findings in relation to our inquiry question:

What effect will changes in teacher pedagogy have on the transition, wellbeing, and academic engagement of the tamariki in Dannevirke?

Methods

This project is based in Dannevirke, a small rural community in the Tararua District, with a population of 5,301. Being a small community allowed us to involve the Dannevirke Kāhui Ako ECE centres and schools in a community approach to transition. We view our project as action research, which McNiff (2013) described as “learning in and through action and reflection” (p. 24). It includes thinking carefully about the actions we are taking to enhance transitions, and researching these actions through data gathering, analysis, and reflection as we seek to understand the influences of the teacher changes in knowledge and pedagogy on outcomes for children.

Time frame

This project is taking place over an 18-month (six-term) period, with the majority of work taking place in 2019. The project team felt it was important to go slowly in the beginning to ensure a deep understanding around the project was held by all participants. We are currently halfway through the data collecting journey. Over this year, deep collaboration has developed within our kāhui ako and, as a project team, we are already working out ways in which this can continue well past the end of the project in 2020.

Participants

There are eight early childhood services and six schools collaborating in this project. We made it available for three ECE teachers to be signed on from each setting and 17 ECE teachers chose to participate. Some of the schools have more than one new entrant teacher and, in total, eight new entrant teachers signed on to the project.

In addition to exploring the pedagogy of these 25 teachers and the general impacts on the wellbeing and academic engagement of the children they teach, we are tracking 11 case-study tamariki and their whānau as the tamariki move from ECE to school. The 11 tamariki and their whānau come from a wide range of ECE settings and are transitioning to different schools. We were careful to select tamariki with diverse cultures, family size, and backgrounds so that we could see trends across the community. Two of the tamariki are identified by their whānau as Māori/NZ European, one as Māori, and the others all NZ European.

Data gathering

The project utilised a range of methods in order to collect rich data: observations; action plans; reflections on professional development; surveys; and interviews. We have provided a brief overview of each of these.

Observations. Each educational setting was allocated 3 release days per term to visit and observe pedagogical practices in another setting. Each teacher had a strict protocol to follow and an observation template to complete after their visits. This not only allowed for teachers to reflect deeply on what they had seen, but also gave them a focus on goals around transition that they would work on within their own settings. Teachers used these observation templates when sharing the pedagogical practice they had seen at our end-of-term reflection sessions, allowing for deep and focused professional dialogue around our key work.

Action plans. To document what is happening for teachers we created action plans that allow us to collaborate, monitor, and change our practice. The action plans were created during the end-of-term reflection sessions and each educational setting was then able to go away with a focused goal to work on. Each term they worked on these goals and looked for evidence of impact on the wellbeing and academic engagement of the tamariki within their settings. We see this as a cycle of inquiry, observing, focusing, learning, taking action/creating goals, and checking the impact this work is having.

Reflections on professional development. Shared professional development opportunities were provided in response to initial findings from the observations, especially aspects teachers had noticed during visits and had further questions around. Some of these have been led by teachers in the project and others by our Expert Partner. Teacher reflections were gathered on each of these in relation to the goals they had developed.

Surveys. To begin, we surveyed all the participating teachers to find out their knowledge around Te Whāriki and NZC. We wanted to find out how well they knew these two documents and how often they referred to them. This gave us a starting point and initial data for us to be able to track changes in teacher knowledge and capabilities.

Interviews. Next, we looked at how we could track tamariki and whānau expectations and experiences around the transition process. We decided to interview these key people at four points across their transition journey.

•2 months before school

•1 week before school

•6 weeks after school

•6 months after school.

These four interview points were chosen to give the project team a deep picture of how tamariki and whānau felt during the transition journey. The first interview of “2 months before school” is when school visits are starting and the whānau is just beginning to step into the world of school with this child. This time was also chosen to see if a positive connection to the ECE setting was evident in the interviews and we will then track to see if this changes after school entry. The interview “1 week before school” provides an opportunity to see how tamariki and whānau feel about leaving their ECE service and moving into the new school setting. The project team felt that, after 6 months of school, tamariki and whānau would have had the opportunity to build strong relationships with their new teachers. This will give us an indication of whether we are heading in the right direction with our current transition practices, or, if not, why this hasn’t happened.

Interviews were completed by an early childhood teacher with whom the tamariki and whānau had an already established relationship. All interviews have been recorded and transcribed for the project team to analyse. A set interview template was made to ensure consistency of questioning across the kāhui ako.

Findings and discussion

Teacher pedagogical understandings are being tracked through observation documents, teacher reflection and goal-setting sessions, initial and final survey results, and evidence produced in relation to teacher goals. Our first findings came from the initial teacher survey.

Teacher survey

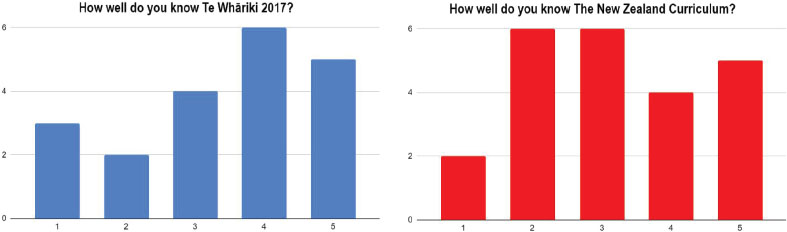

Of the 25 participating teachers, 18 completed the first survey; 12 were ECE teachers and four from schools (with two not stating which sector they worked in). Initial findings when surveying teachers showed us that there was variation in how well teachers knew each other’s curriculum. Teachers rated themselves on a scale of 1–5, with 1 being “little knowledge” of the curriculum and 5 being “a confident user”. Figure 1 shows that there appeared to be greater confidence with Te Whāriki (50% of teachers rating themselves 4 or 5), compared with NZC (only 22.3% of teachers rating themselves 4 or 5). This was perhaps not surprising, given the majority of respondents were from ECE; however, it seemed there were a number of teachers possibly not feeling confident with their own curriculum, let alone one from the other sector.

FIGURE 1. TEACHER SELF-RATINGS OF THEIR KNOWLEDGE OF TE WHÅRIKI AND NZ

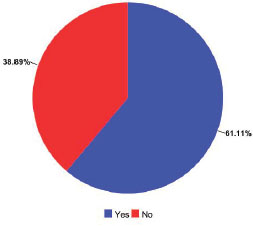

Figure 2 shows there was also variation around the links that teachers were making between these two curriculum documents in their practice. At the start of the study, 61% of teachers reported that they were not making links between the two curriculum documents. We hope to be able to see over the project period that these data change, that there is a growth in understandings, and a growth in the links teachers make between the two curricula.

Our initial survey findings aligned with our experience before the project and indicated that more work was needed to help teachers if they are to develop an understanding of both Te Whāriki and NZC and to use this knowledge in practice to make links between the two, which ERO (2015) identified as important for supporting transitions. The Pathways section in Te Whāriki (Ministry of Education, 2017) has provided a place to begin this exploration but our experience has been that teachers valued support to begin this process. We have held a number of professional development sessions on both curricula and noted at a recent workshop that the teachers now showed greater confidence in using both documents to collaboratively analyse the learning in some Learning Stories.

Tamariki and whānau interviews

The tamariki and their whānau were all interviewed before the children started school. In this first round, 100% of tamariki and whānau shared comments that suggested positive engagement with their current settings:

Coz it’s my favourite time when I’m coming to preschool. (C1, Māori/NZ European)

Playing with the cars. I like playing on the swings. [Another child] likes me to push him on the swing. (C9, NZ European)

[We love] everything, you guys, the teachers, the whole system. (Whānau C8, Māori)

There were some examples of negative engagement but these tended to be quite specific, such as:

I don’t like playing with balls. I don’t like playing on the spinny tyre. It makes me dizzy. (C3, NZ European)

FIGURE 2. TEACHERS WHO REPORTED THEY ACTIVELY MAKE LINKS BETWEEN TE WHÅRIKI AND NZC

Drawing on the work of van Gennep (1908/1960), Fabian (2002) and Garpelin (2014) described transition as being on the threshold (limen) between the familiar and the new. We can see that 2 months before starting school the tamariki seemed engaged and settled in their current context/status/position at ECE. Just under half of the whānau described this in terms of their tamariki having a real sense of belonging to their early childhood setting. For example, this parent noted the knowledge that teachers had of her child:

I remember when I first started here, and you’d tell me things about my child, and I was blown away by how well you knew her, because I would look around at how many kids, and I’d think how could you possibly know really intimate stuff about who she is as a little person. (Whānau C1, Māori/NZ European)

While they were settled in ECE, the tamariki were aware of the move to school ahead. There appeared to be a slight disparity between how tamariki felt about their transition and what their whānau said. Almost all the whānau (91%) spoke positively about their tamariki transitioning to school, compared with 64% of tamariki who spoke positively about transitioning to school:

Excited, a little bit nervous, School visits make him aware bigger school, bigger kids, he seems to be pretty keen. (Whānau C5, NZ European)

She’s very excited ... most, mostly everyone is happy she’s going to [name of school] too. (Whānau C10, Māori)

Early research by Dockett and Perry (1999) highlighted that children, parents, and teachers may all view the transition to school differently and 20 years later this remains an important consideration. If we take time to understand the feelings and experiences of tamariki we will be better equipped to support them.

Although some tamariki were not as positive about starting school as their whānau, only three tamariki (27%) made a negative comment about their transition to school. For example:

I am shy when I talk to Mrs ______ [new entrant teacher]. (C8 NZ European)

Only two whānau (18%) made a negative comment about the transition of their tamariki. For example:

I think she is a wee bit nervous going into an environment with no friends. (Whānau C3, NZ European)

These comments were consistent with earlier research that highlights the importance of relationships in transition to school (Peters, 2010) and suggests these tamariki do not yet have a sense of belonging or a relationship with their new entrant teacher or peers. We will be able to track and see if this changes over time.

Sometimes a negative comment showed the child’s mixed emotions:

Child: “My sister gets a little bit sad when she goes to big school. And I get nervous when I’m going to big school.”

Later in the interview

Interviewer: “How do you feel about starting at [name] school?”

Child: “Happy. Nervous … and then I get sad when I’m nervous.” (C1, Māori/NZ European)

The liminal phase of a transition is a time both of challenges and of possibilities (Garpelin, 2014; Peters & Sandberg, 2017) so anticipating it with a mix of nervousness and excitement might be expected. However, we want to ensure that the sense of nervousness is not so great that it impacts negatively on the children’s wellbeing and engagement.

Overall, these initial interview findings highlight the importance of building relationships and connections with tamariki during the transition process. The wellbeing of these tamariki will be looked at closely when analysing further interviews.

Teacher observations and goal setting

So far, there are positive interactions from teachers regarding the project. Teachers’ knowledge around transition practices and what works best in our community is being shared between teachers. Teachers are creating achievable goals to work on throughout the term and are able to find new skills to support these goals when they head out for their next observations and through the reflection and professional-development sessions:

It’s great to see the passion and respect between schools and early childhood and vice-versa. There is a lot of strength and communication being developed. (ECE teacher)

I like how everything is linked, how we have the ability to discuss new obtained knowledge, and challenge pedagogy. (NE teacher)

Great to see the genuine and honest sharing between ECE and NE teachers. I have increased my understanding and knowledge of Te Whāriki but need more knowledge in this area to use it. (NE teacher)

I have learnt a lot about how both the NZC and Te Whāriki complement each other and how to use these effectively for planning and documentation. (ECE teacher)

The goals are those that the ECE services and schools are collectively working towards rather than individual teacher goals. Looking across the community, we have noticed trends within each sector. ECE teachers have identified the potential value of improving tamariki self-help and independence skills, as these will assist the children by making them more confident in their new environment, and 50% of early childhood settings have chosen to focus on these key skills. This included tamariki looking after their own belongings, finding shoes, putting on jackets/jumpers, and taking responsibility for themselves. Their focus has clear links with participating and contributing as a key competency in NZC. Some services also advised parents that these were key skills that tamariki were working on so that this could be supported at home:

We want children to be more confident at doing things for themselves. (ECE teacher)

For teachers of new entrants there has also been a trend noticed, with 50% of schools working on establishing how play-based learning can be used within their classroom setting. This goal was picked up by new-entrants teachers as, through the observations, they were able to see the potential value of making their environment and teaching pedagogy more familiar to the tamariki who were transitioning to school. Before making this change there seemed to be more of a jump into formal learning:

Play is culturally responsive. The children are relaxed and happy. They feel confident to interact with the teachers, parents and other adults in the room and wider school. The transition from ECE for the children in this class would be very fluid and they are given opportunities to play and some activities involve using sounds, numbers etc. which they can participate in when they wish or when they are ready to. (NE teacher)

These teachers have changed how their new-entrant classroom environment is set up to allow and create opportunities in play. Some teachers have also changed timetables to allow for free play when tamariki arrive at school. They noted how relaxed tamariki are on arrival to school and how the teachers’ relationships with tamariki are much stronger having spent time interacting with them during play. Davis (2015) also documented similar findings from a play-based learning time at the start of the school day where the NZC key competency relating to others was focused on. Given the OECD Starting Strong V report indicated that “the more age- and child-appropriate the pedagogical practices, the greater the benefits for children’s social and cognitive development” (OECD, 2017, p. 16), we are exploring further what this might look like in Aotearoa New Zealand classrooms.

Conclusion

This project’s initial findings have highlighted that, despite a range of research and policy recommendations regarding the value of working together across sectors and having a strong understanding of both ECE and school curricula, teachers may feel they do not have sufficient knowledge to put this into practice. Our project has demonstrated that it is possible for teachers across a community to work together collaboratively to deepen their curriculum knowledge. The initial findings indicate the power of teachers working together across sectors for the benefit of the tamariki and whānau and to enhance wellbeing and engagement in learning both within ECE settings and within schools and as tamariki make the transition into school. The TLIF funding has made it possible to research practice, but the elements of working together on shared goals, drawing on each other’s expertise, and thoughtful exploration of curriculum are pedagogical practices that can apply in any community. Teachers working together in this kāhui ako has led them to a commitment to developing their knowledge and understandings and they have a desire to see learning from a different perspective.

In addition, our early findings indicate that tamariki are potentially facing the move to school with a mix of fear and excitement, and it is important for adults to recognise that children may not be feeling quite as positive as their whānau. The importance of the relationships tamariki have with teachers and friends has been a feature of earlier research (see Peters, 2010) and was reiterated here. Knowing that relationship building is paramount for developing effective transition pathways (ERO, 2015; Ministry of Education, 2017; Peters, 2010), we can safely say that, at this point, the Dannevirke Kāhui Ako is working towards building relationships in an extremely positive and proactive way. Relationships across the sectors have moved from surface contact to deep and meaningful pedagogical discussions and practices. This means that the tamariki within the Dannevirke community have a team of people behind them who have a vested interest in their transition, wellbeing, and academic engagement. We know this project will continue to develop and teachers will continue to make changes to their pedagogical practices and classroom environments. We hope the learning of tamariki within our community will glide seamlessly on from early childhood into primary school.

Acknowledgement

We are very grateful to the Ministry of Education Teacher-led Innovation Fund that is funding this project. Our thanks also go to all those involved as colleagues, researchers, and participants.

References

Davis, K. (2015). New-entrant classrooms in the re-making. Christchurch: Core Education. Retrieved from https://www.academia.edu/33447412/New_Entrants_in_the_re-making

Dockett, S., & Perry, B. (1999). Starting school: What matters for children, parents and educators? Early Childhood and Care, 159, 107–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/0300443991590109

Education Review Office. (2015). Continuity of learning: Transitions from early childhood services to schools. Retrieved from https://www.ero.govt.nz/publications/continuity-of-learning-transitions-from-early-childhood-services-to-schools/

Fabian, H. (2002). Children starting school. London, UK: David Fulton.

Garpelin, A. (2014). Transition to school: A rite of passage in life. In B. Perry, S. Dockett, & A. Petriwskyj (Eds.), Transitions to school—International research, policy and practice (pp. 117–128). New York, NY: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7350-9_9

Kōrero Mātauranga. (2018). He taonga te tamaiti—Every child a taonga: Strategic plan for early learning 2019–29. Draft for consultation. Retrieved from https://conversation.education.govt.nz/conversations/early-learning-strategic-plan/

McNiff, J. (2013). Action research: Principles and practice (3rd ed.). Abingdon, UK: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203112755

Ministry of Education. (2007). The New Zealand curriculum. Wellington: Learning Media.

Ministry of Education. (2008). Te marautanga o Aotearoa. Wellington: Learning Media.

Ministry of Education. (2017). Te whāriki: He whāriki mātauranga mō ngā mokopuna o Aotearoa—Early childhood curriculum. Wellington: Author.

OECD. (2017). Starting strong V: Transitions from early childhood education and care to primary education. Paris, France: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264276253-en

Peters, S. (2010). Literature review: Transition from early childhood education to school. Wellington: Ministry of Education. Retrieved from https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/publications/ECE/98894/Executive_Summary

Peters, S., & Sandberg, G. (2017). Bridges, borderlands and rights of passage. In N. Ballam, B. Perry, & A. Garpelin (Eds.), Pedagogies of educational transitions: European and antipodean research (pp. 223–237). Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-43118-5_14

van Gennep, A. (1960). Rites of passage (M. B. Vizedom & G. L. Caffee Trans.) Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. (Original published in French in 1908)

Lisa Bond is the manager of First Years Preschool, one of the early childhood services attached to the project. Lisa is also the ECE rep on the Dannevirke Ka-hui Ako management group.

Jo Brown is the early years’ co-ordinator at Tararua REAP. She also represents ECE on the Dannevirke Ka-hui Ako management group.

Jenna Hutchings is one of the across-school teachers in the Dannevirke Ka-hui Ako. She works primarily with ECE and the junior end of primary school. Jenna is also the assistant principal and one of the new entrant teachers at Dannevirke South School.

Sally Peters is an associate professor at Waikato University and head of school, Te Kura Toi Tangata School of Education. Sally is the Expert Partner working with the Dannevirke Ka-hui Ako Teacher Led Innovation Fund Project.