He kai kei aku ringa

Practical advice for developing a system-wide approach to transforming outcomes for ākonga

Melinda Webber, Mohamed Alansari, Rāhera Meinders, Jean M. Uasike Allen, Nicola Bright, Renee Tuifagalele, Sinead Overbye, and Mengnan Li

Key points

Lifting the educational trajectories of Māori and Pasifika ākonga can be achieved through:

•strong and positive motivational beliefs about learning, as well as participation in learning experiences that are culturally embracing, aspirational, and future oriented

•robust networks of support and role models, both in and out of school, who enable and embody success

•home–school partnerships that are built on mutual care, respect, and a collective vision for ākonga and their communities

•schools understanding what drives whānau engagement in education and purposefully inviting them to partner in their children’s learning

•sustained attention to school-wide conditions and teaching practices that are strengths based, ambitious, and contextually tailored to the needs of Māori and Pasifika ākonga

•effective and reflexive teachers who leverage positive relationships, demonstrate high expectations, and seek ongoing opportunities for professional learning and development.

Although the existing literature has always established strong ties between student motivation, engagement, and learning outcomes, few studies have focused on the motivation and engagement of Māori and Pasifika students. Also, large-scale quantitative and qualitative studies that focus solely on the views of Māori and Pasifika learners (i.e., not compared to their Pākehā/NZ European counterparts) are limited. In response, the COMPASS project (comprising seven studies) has examined the ways Māori and Pasifika ākonga and whānau successfully navigate their way through the schooling system, maintaining positive motivation, academic engagement, cultural connectedness, and high aspirations. We also set out to highlight the practices, pedagogies, and beliefs of school leaders, teachers, and whānau committed to Māori and Pasifika student success. In this article, we bring together the findings from across all seven COMPASS studies to provide practical recommendations for schools, their communities, and others who are committed to enabling Māori and Pasifika students to flourish.

Introduction

Teaching is multifaceted; it is simultaneously “a discipline grounded in scientific research, an art requiring creativity, and a craft necessitating constant collaborative reflection and improvement” (OECD, 2025, p. 3). Consequently, teachers need a deep understanding of both “content and pedagogical strategies informed by research, but also adaptability, creativity, and responsiveness. Teaching is a science, but so too an art and craft” (OECD, 2025, p. 8). It is with these complexities in mind that we synthesise the findings of seven COMPASS studies in order to share what numerous ākonga, whānau, and teachers have taught us about quality teaching and learning.

Who are we? Positioning ourselves

We are a group of scholars, Indigenous and allies, who are committed to undertaking research that highlights the success anchors, conditions, and practices needed to inform (and transform) educational outcomes for Māori and Pasifika ākonga. We have written this article with school communities in mind—specifically school leaders, teachers, and whānau—to make our research findings accessible and applicable to their professional and personal lives.

It is during turbulent and/or busy times where schools would look to research like this for positive strategies to adapt, an optimistic outlook to adopt, as well as validation for all the good work they do. It is for those reasons we have chosen to adopt a strengths-based approach in our work, not to mask inequities or problems of/in practice, but rather to equip school communities with the resources and thinking they need to do more of to bring about the change they wish to see in ākonga outcomes. We have also used and operationalised terms such as “flourishing ākonga” in our work, to highlight an ideal state or goal that schools can build impetus around and create positive increments towards. It is also for those reasons that we have looked to identify “what works”—as opposed to “what doesn’t”—through our work, and chosen to highlight synergetic and similarly effective strategies that could benefit both Māori and Pacific ākonga. This is especially important since the patterns and insights we have identified separately for Māori and Pacific ākonga appeared to be more similar than not, and most experiences and perceptions reported by whānau members have highlighted very similar patterns in terms of ways to strengthen school environments for flourishing ākonga. Therefore, we focus on both “Māori and Pasifika” ākonga in this article, not as a way to dilute the uniqueness and diversity of the peoples—iwi, aiga, and the like—within each group, but instead to signal that our findings were similar across the board.

What do we know about flourishing Māori and Pasifika ākonga?

Māori and Pasifika ākonga flourish at school when they are encouraged to work in mana-ful ways alongside significant others to identify and further develop their capabilities, strengths, interests, and aspirations for the future. In addition, they thrive emotionally, socially, culturally, and academically when good information about them is shared between whānau, teachers, and other key learning partners. The COMPASS research has shown that many Māori (64% primary, 81% secondary) and Pasifika (71% primary, 66% secondary) ākonga are flourishing, thriving, or striving at school (Alansari et al., 2022). They are generally motivated to learn, engaged in classroom activities and discussions, feel supported, and are proud of their cultural identities. The research also shows that high levels of ākonga motivation and engagement are predictive of positive academic efficacy, perceptions of academic and social support, and cultural pride. Finally, the COMPASS research shows that what teachers are doing in the classroom and how whānau are seen to partner in learning has a significant impact on how the ākonga see and apply themselves academically and socially.

Developing a positive sense of mana

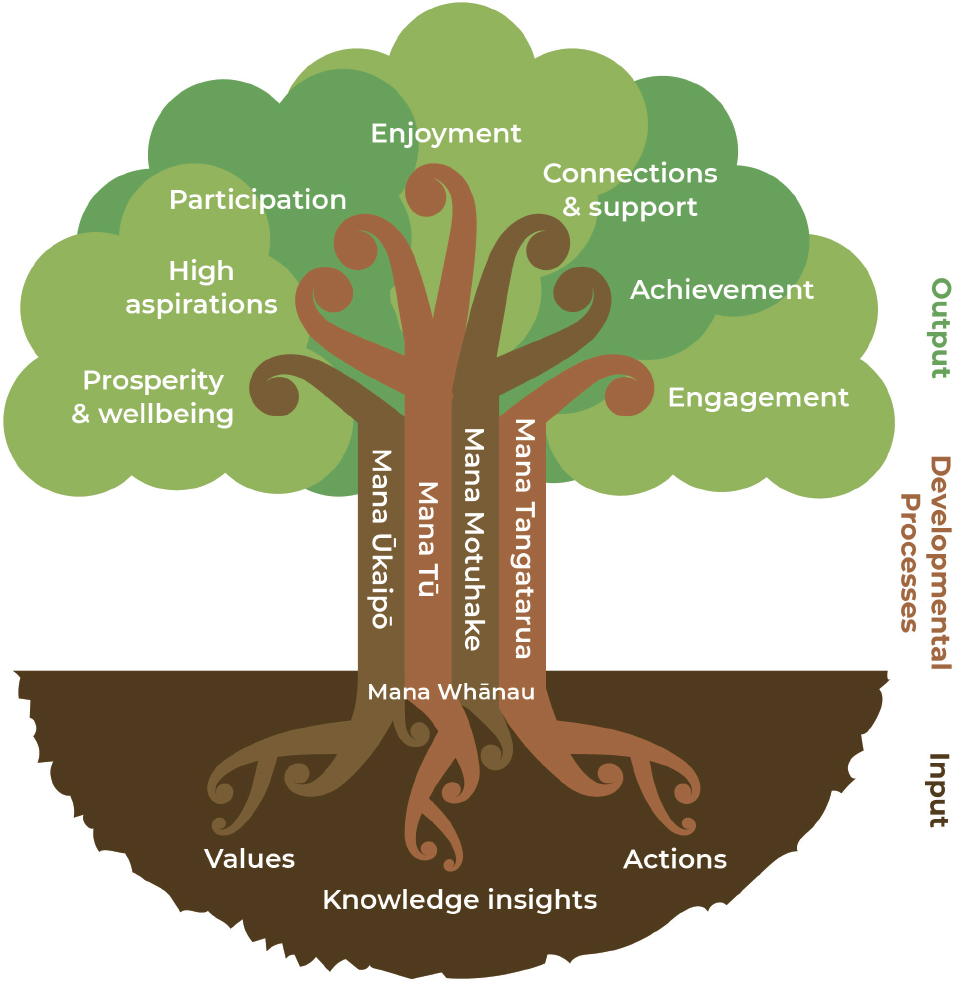

Māori and Pasifika ākonga flourish when they experience school as a context that affirms their mana, including their sense of authority, influence, self-efficacy, purpose, pride, and belonging. Previous research (Webber, 2024) has asserted that all ākonga are driven to actualise their mana in educational contexts, which can have a profound impact on their perceived “ability to impact upon, effect and positively transform the lives of others” (Dell, 2017, p. 89). The mana model (Webber, 2024; Webber & Macfarlane, 2020) contends that schools are an influential space to harness and transform students’ mana, motivation, knowledge, skills, capabilities, and interests. The mana model proposes five optimal conditions for Māori student success: Mana Whānau (connectedness to others and collective agency); Mana Ūkaipō (belonging and relationship to place); Mana Motuhake (positive self-concept and embedded achievement); Mana Tū (social–psychological competence); and Mana Tangatarua (a diverse knowledge base and skill set). These five optimal conditions are not linear or hierarchical in nature, but instead evolve, overlap, and flourish depending on the school or classroom environment. Importantly, the mana of ākonga is always present, ebbing and flowing in response both to classroom content, and to conditions in the context for learning. Additionally, Bright and Webber (2024) found that whānau, teachers, and school leaders play a critical role in the development of tamariki, particularly in terms of collectively nurturing their mana, wellbeing, and success in school.

Motivation, engagement, and positive self-beliefs: Influences on ākonga success

Critical to student success and ongoing school engagement is their motivation to learn and engagement patterns at school. Motivation in education can be intrinsic, extrinsic, or influenced by whānau values, and individuals often experience different motivations simultaneously (Reschly & Christenson, 2022). COMPASS explored how whānau perceive their Māori children’s motivations for school, noting that whānau perceptions often mirror their children’s motivations. Madjar et al. (2016) investigated the impact of parental attitudes on children’s motivation towards homework. They discovered that, when parents emphasised mastery goals, such as deep learning and self-improvement, it was positively associated with children’s own mastery orientations. In contrast, a focus on performance goals—such as competing with peers or avoiding negative evaluations—was linked to children’s performance-approach and performance-avoidance orientations, with these effects mediated by how children perceived their parents’ goals. Intrinsic motivation has been found to be linked to positive attitudes towards learning (Wigfield et al., 2012), greater persistence (Miller et al., 2020), enhanced metacognitive processing (Hoyle & Dent, 2018), and better wellbeing (Park et al., 2024). Conversely, findings on extrinsic motivation’s impact on achievement were mixed, with some studies suggesting negative effects (Lee et al., 2016) and others indicating positive correlations (Senko, 2019). Whānau motivation, such as the desire to make one’s whānau proud, is also crucial for student success (Webber & Macfarlane, 2020). However, contrary to prior research that has reinforced a dual, and at times binary, notion of motivation, our COMPASS study 1 findings (Alansari et al., 2022) showed both intrinsic and extrinsic motivation to be positive predictors of self-reported wellbeing and educational outcomes. We also found that whānau was another positive predictor of student outcomes, as well as a positive correlate with the other two motivation types. The COMPASS study 1 contended that students are attuned to the multiple and simultaneous reasons why attending school can be important for their short- and long-term goals (both tangible and intangible) and are therefore able to utilise that knowledge to fuel their engagement with various aspects of school(ing).

Academic engagement is a well-established factor in the literature, with known links to enhanced achievement outcomes—a multifaceted construct that includes affective/emotional, behavioural, and cognitive aspects (Reschly & Christenson, 2022). Behavioural engagement pertains to students’ actions and participation in school activities, emotional engagement involves their emotional responses to school and learning enjoyment, and cognitive engagement reflects the mental effort invested in learning. Research showed that school engagement can improve academic performance, promote school attendance, and reduce risky behaviours (Lippman & Rivers, 2008). Despite previous underestimation of its importance, fostering school engagement has now been recognised as vital for enhancing academic motivation and success (Bosnjak et al., 2017; Chodkiewicz & Boyle, 2016; Fredricks et al., 2004). Therefore, understanding the motivational and engagement drivers for Māori and Pasifika ākonga, and how these relate to their learning beliefs and outcomes, is likely crucial for improving educational strategies and support mechanisms.

Leveraging home–school partnerships: The importance of whānau and schools working together

Research into whānau involvement and engagement has highlighted the significant role of whānau contexts in influencing student engagement, both directly and indirectly through whānau beliefs and expectations (Reschly & Christenson, 2019). Whānau behaviours, such as monitoring progress and active involvement, have been identified as essential for supporting and enhancing students’ engagement with their education (Upadyaya & Salmela-Aro, 2013; Wilder, 2014). Key aspects such as whānau knowledge of school activities, effective communication with teachers, and support for autonomy were found to be linked to increased student engagement and better academic outcomes (Im et al., 2016). Furthermore, whānau autonomy support and a focus on mastery goals contributed to higher engagement, persistence, intrinsic motivation, and academic achievement (Reschly & Christenson, 2019).

Previous research has also highlighted the influence of whānau and cultural values on children’s success motivations. Rubie-Davies et al. (2018) contended that attention to positive learning-focused relationships with Māori students’ whānau and community can be powerful, particularly if schools invited the participation and decision making and teaching activities related to the children’s learning. These authors also argued that schools must cultivate a climate in which whānau feel comfortable to initiate involvement in their children’s education and should provide them with the appropriate opportunities to do so. Webber et al. (2021) found that, for Ngāpuhi secondary students in Aotearoa New Zealand, whānau role models and cultural values were crucial in guiding their educational choices. These students admired role models who embodied tenacity, ambition, and self-determination—traits mirrored in their tūpuna. In addition, Overbye (in Alansari et al., 2022) found that whānau role models can contribute to ākonga flourishing by modelling cultural competence and confidence, supporting and mentoring ākonga, encouraging and celebrating ākonga achievements, and helping ākonga to achieve their aspirations. Finally, similar findings were echoed by Park and colleagues (2024), who compared success beliefs and wellbeing among Korean youth located in New Zealand and abroad and found that cultural norms—likely emphasised by parents—were highly influential to how Korean children viewed their success beliefs and motivation to learn. These findings highlight the pivotal role of whānau culture and whānau involvement in shaping children’s learning behaviours. Understanding how whānau engage with their children’s education and how this engagement interacts with cultural values is therefore crucial.

COMPASS: A research programme

COMPASS 1–7 studies: An overview

The COMPASS research programme focused on gathering data that tell us about how Māori and Pasifika ākonga navigate schooling, including the ways whānau, teachers, and school leaders can make provisions that enable them to succeed and flourish in educational settings.

COMPASS adhered to ethical principles and practices, including informed consent, protection of vulnerable students, anonymity, and confidentiality as outlined by kaupapa Māori protocols (G. H. Smith, 1997; L. T. Smith, 2005). A kaupapa Māori approach to the project ensured a respectful, culturally responsive, and appropriate pathway was used for undertaking this important work alongside school communities. Teachers and school leaders were involved in the gathering of the data, liaison with ākonga and whānau, and included in the analysis and interpretation of school-level findings.

COMPASS was a strengths-based research project that set out to investigate how ākonga learn, succeed, and thrive at school, through surveying a large number of ākonga (n = 18,996), whānau (n = 6,949), and kaiako (n = 1,866) respondents from 102 schools across Aotearoa New Zealand. For the purposes of the current article, we have focused on the views and experiences of Māori (n = 4,651) and Pasifika (n = 1,192) ākonga, Māori whānau (n = 1,665), Pasifika whānau (n = 362), and kaiako Māori (n = 311).

In this article, we undertake a retrospective, secondary analysis of the key findings across the seven COMPASS studies, identifying common themes, threads, and insights. This synthesis of the broader findings allowed us to highlight the strengths-based practices, qualities, and pedagogies that ākonga, whānau, and teachers believe are important for the success of Māori and Pasifika ākonga in education.

As part of the analysis, we have developed three tables through which we present the key findings, translated into actions and practical recommendations for key groups (whānau, teachers, and school leaders) to amplify positive outcomes for Māori and Pasifika ākonga.

Study 1 (Alansari et al., 2022) analysed quantitatively the motivation and engagement patterns of Māori and Pasifika ākonga and had established statistically significant and positive associations between student beliefs, their educational aspirations, support networks, and academic efficacy.

Studies 2–4 analysed qualitatively the perspectives and views of ākonga Māori (Overbye, in Alansari et al., 2022), kaiako Māori (Edge, in Alansari et al., 2022), and Pasifika whānau (Tuifagalele, in Alansari et al., 2022), to ascertain what makes a positive difference for Māori and Pasifika ākonga. These accounts highlighted the importance of positive role models, home–school partnerships, and the teaching pedagogies in shaping the success experiences of ākonga.

Study 5 (Tuifagalele et al., 2024) focused on Pasifika whānau perspectives, by bringing to the fore the values and qualities they believe are important in helping their children successfully navigate schooling in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Study 6 (Bright & Webber, 2024) focused on whānau Māori experiences and perspectives, by highlighting what is most important for them and for kaiako to do in order to support tamariki Māori to flourish. The study highlighted the role of identity, strengths-based teaching approaches, and home–school partnerships in making learning enjoyable and fruitful.

Study 7 (Alansari et al., 2025) further examined the role of home–school partnerships, through a quantitative analysis of whānau Māori experiences and involvement in their children’s schools, including their views of their children’s school engagement. The study concluded that whānau who are in active partnerships with their children’s schools were more likely to report positive views of their children’s motivation, engagement, and learning. More generally, the study emphasised the critical role of school enjoyment and motivation to whānau engagement in education.

What did COMPASS findings teach us about developing a system-wide approach to transforming outcomes for ākonga?

Framing the findings through a value/know/do model

Our analyses revealed that the findings across all studies can be categorised into three areas based on what participants told us about whānau, teachers’, and school leaders’ actions to positively transform outcomes for Māori and Pasifika ākonga in education:

•the things that whānau, teachers, and school leaders must value, in terms of espoused beliefs, dispositions, qualities, and non-negotiables, that transcend school life and are known to have a long-term impact on Māori and Pasifika ākonga outcomes

•the things that whānau, teachers, and school leaders must know, in terms of insights, strategies, how-to’s, and processes, to translate the values into actionable steps and create school-wide and classroom shifts in practice

•the things that whānau, teachers, and school leaders must do, in terms of actions and practices, to enact valued aspirations and values and create impetus and positive improvements towards long-term vision for Māori and Pasifika ākonga success.

As shown in Tables 1–3, we offer our findings through a value/know/do framework as articulated by our participants, but also as a way of showing progression or connection between what schools espouse and enact. We also offer Figure 1 after the tables, which is a visual representation of how we envision the values, knowledge insights, and actions to interact with the mana model to transform ākonga outcomes. That is, in order for schools to transform outcomes for ākonga, they must first decide on the values, often manifested in the form of a rationale, that underpin their intended change. This would then be followed by a discussion of what schools need to know to realise and enact such values, followed by agreement on a set of key actions (or actionable next steps) that are well supported, resourced, and valued.

Table 1. Conditions needed to transform outcomes for ākonga—whānau

Table 2. Conditions needed to transform outcomes for ākonga—teachers

Table 3. Conditions needed to transform outcomes for ākonga—school leaders

Figure 1. How we envision the values, knowledge insights, and actions to interact with the mana model to transform ākonga outcomes

Recommendations for engagement with the findings

It is often in the most complex situations and school contexts where simple checklists or tables like the ones in this article can be most useful. Teachers and school leaders are expected to integrate a staggering volume of information to inform their planning, teaching, and practice. Similarly, whānau are often juggling numerous responsibilities alongside prioritising the education of their tamariki. Among these demands and pressures, schools and whānau are still expected to establish and sustain supportive home–school relationships centred on improving outcomes for ākonga. We know educational success is not a simple matter and there is not a prescribed formula or process that will suit everyone. In response, we offer Tables 1–3 as a reminder that there is a range of different actions we could take in our homes, classrooms, and schools to help ākonga flourish in education.

Whānau, teachers, and leaders can use the information presented in the tables to enhance Māori and Pasifika ākonga learning, motivation, engagement, and achievement at school. The tables are a synthesis of research findings from seven different empirical studies, simplified into three tables to highlight research-informed best practice and ensure consistency of application and collective focus. They are also simple, flexible, and designed to help whānau, teachers, and school leaders set clear objectives, track complex processes, promote accountability, and prevent critical details from being overlooked.

When engaging with the tables, it might be useful for leadership teams and heads of departments to lead their colleagues in discussions using the following questions (or an iteration of them):

1.Audit: Which of these values, knowledge insights, and actions do you already enact well, somewhat well, or not well at all? Do you espouse more of the values and enact fewer of the actions? Or do you do lots of actions that aren’t necessarily driven by values or knowledge as to why these things matter?

2.Plan: Which values, knowledge insights, or actions can be the focus for your next annual plan? What support or resourcing might your team need to enact change?

3.Involve: How might you invite Māori and Pasifika ākonga and whānau feedback on these changes, including the extent to which you have been effective at implementing them?

4.Timeline: How long might it take you to learn, plan, and adapt for change in practice based on what you want to value, know, and do more of?

5.Review and monitor: What evidence, data, and/or insights should you gather to examine the extent to which teaching and learning outcomes are improving because of changes you made to what you value, know, and do in your school?

Conclusion

The purpose of the article is to synthesise an extensive programme of research focused on unpacking ways to support the success and aspirations of Māori and Pasifika ākonga. In doing so, we highlight the conditions needed to ensure ākonga mana, motivation, cultural identities, and academic potential are nurtured and sustained through(out) their educational journeys. The article argues that lifting the educational trajectories of Māori and Pasifika ākonga requires concerted efforts to unpack what school leaders, teachers, and whānau value, know, and do to positively transform student motivation, engagement, and achievement. This involves ensuring tamariki hold strong and positive motivational beliefs about learning and their potential and have opportunities to participate in learning experiences that are culturally embracing, aspirational, and future oriented.

Māori and Pasifika ākonga success relies on robust networks of support, both in and out of school, along with home–school partnerships that are built on mutual care, respect, and a collective vision for ākonga and their communities. The findings demonstrate that what whānau, teachers, and school leaders value, know, and do must be strengths based, ambitious, and contextually tailored to ensure Māori and Pasifika ākonga flourish in education. Finally, effective and reflexive teachers who leverage positive relationships, demonstrate high expectations, and seek ongoing opportunities for professional learning and development, are key to transforming the learning trajectories of ākonga.

References

Alansari, M., Webber, M., & Li, M. (2025). COMPASS: Whānau partnerships with school—patterns and associations with Māori students’ learning. New Zealand Council for Educational Research. https://doi.org/10.18296/rep.0070

Alansari, M., Webber, M., Overbye, S., Tuifagalele, R., & Edge, K. (2022). Conceptualising Māori and Pasifika aspirations and striving for success (COMPASS). New Zealand Council for Educational Research. https://doi.org/10.18296/rep.0019

Bosnjak, A., Boyle, C., & Chodkiewicz, A. R. (2017). An intervention to retrain attributions using CBT: A pilot study. The Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 34(1), 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1017/edp.2017.1

Bright, N., & Webber, M. (2024). COMPASS: Poipoia ngā Tamariki—How whānau and teachers support tamariki Māori to be successful in learning and education. New Zealand Council for Educational Research. https://doi.org/10.18296/rep.0054

Chodkiewicz, A. R., & Boyle, C. (2016). Promoting positive learning in students aged 10–12 years using attribution retraining and cognitive behavioural therapy: A pilot study. School Psychology International, 37(5), 519–535. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034316667114

Dell, K. (2017). Te hokinga ki te ūkaipō: Disrupted Māori management theory; harmonising whānau conflict in the Māori land trust [Doctoral thesis, The University of Auckland]. https://hdl.handle.net/2292/36918

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. https://doi. org/10.3102/00346543074001059

Hoyle, R. H., & Dent, A. L. (2018). Developmental trajectories of skills and abilities relevant for self-regulation of learning and performance. In D. H. Schunk & J. A. Greene (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation of learning and performance (pp. 49–63). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315697048-4

Im, M. H., Hughes, J. N., Cao, Q., & Kwok, O. (2016). Effects of extracurricular participation during middle school on academic motivation and achievement at grade 9. American Educational Research Journal, 53(5), 1343–1375. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831216667479

Lee, C. S., Hayes, K. N., Seitz, J., DiStefano, R., & O’Connor, D. (2016). Understanding motivational structures that differentially predict engagement and achievement in middle school science. International Journal of Science Education, 38(2), 192–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2015.113 6452

Lippman, L., & Rivers, A. (2008). Assessing school engagement: A guide for out-of-school time program practitioners. Child Trends. https://www.childtrends.org/publications/assessing-school-engagement-a-guide-for-out-of-school-time-program-practitioners-2

Madjar, N., Shklar, N., & Moshe, L. (2016). The role of parental attitudes in children’s motivation toward homework assignments. Psychology in the Schools, 53(2), 173–188. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21890

Miller, C. J., Perera, H. N., & Maghsoudlou, A. (2020). Students’ multidimensional profiles of math engagement: Predictors and outcomes from a self-system motivational perspective. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(1), 261–285. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12358

OECD. (2025). Unlocking high-quality teaching. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/f5b82176-en

Park, J. J., Brown, G. T. L., & Stephens, J. M. (2024). In between Korean and New Zealander: Extrinsic success beliefs and well-being of Korean youth in New Zealand. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 99, 101943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2024.101943

Reschly, A. L., & Christenson, S. L. (2019). The intersection of student engagement and families: A critical connection for achievement and life outcomes. In J. Fredricks, A. L. Reschly, & S. L. Christenson (Eds.), Handbook of student engagement interventions: Working with disengaged youth (pp. 57–71). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-813413-9.00005-X

Reschly, A. L., & Christenson, S. L. (Eds.). (2022). Handbook of research on student engagement. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-07853-8

Rubie-Davies, C. M., Webber, M., & Turner, H. (2018). Māori students flourishing in education: Teacher expectations, motivation and sociocultural factors. In G. Lief & D. McInerney (Eds.), Big theories revisited (Vol 2). Research on sociocultural influences on motivation and learning series (pp. 213–236). Information Age Publishing.

Senko, C. (2019). When do mastery and performance goals facilitate academic achievement? Contemporary Educational Psychology, 59(Article 101795). https://doi.org/10.1016/j. cedpsych.2019.101795

Smith, G. H. (1997). Kaupapa Māori: Theory and praxis [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. The University of Auckland.

Smith, L. T. (2005). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples. Zed Books.

Tuifagalele, R., Uasike Allen, J., Meinders, R., & Webber, M. (2024). COMPASS: Whānau Pasifika navigating schooling in Aotearoa New Zealand. New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Upadyaya, K., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2013). Engagement with studies and work. Emerging Adulthood, 1(4), 247–257. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696813484299

Webber, M. (2024). Teaching the mana model—a Māori framework for reconceptualising student success and thriving. Set: Research Information for Teachers, (1), 2–11. https://doi.org/10.18296/set.1545

Webber, M., Horne, R., & Meinders, R. (2021). Mairangitia te angitū: Māori role models and student aspirations for the future—Ngāpuhi secondary student perspectives. MAI Journal, 10(2), 125–136.

Webber, M., & Macfarlane, A. (2020). Mana tangata: The five optimal cultural conditions for Māori student success. Journal of American Indian Education, 59(1), 26–49. https://doi.org/10.1353/jaie.2020.a798554

Wigfield, A., Cambria, J., & Eccles, J. S. (2012). Motivation in education. In R. M. Ryan (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of human motivation (pp. 463–478). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195399820.013.0026

Wilder, S. (2014). Effects of parental involvement on academic achievement: A meta-synthesis. Educational Review, 66(3), 377–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2013.780009

Further readings

•COMPASS 1: Conceptualising Māori and Pasifika aspirations and striving for success (COMPASS) | New Zealand Council for Educational Research https://www.nzcer.org.nz/research/publications/conceptualising-m-ori-and-pasifika-aspirations-and-striving-success-compass

•COMPASS 2: COMPASS: Whānau Pasifika navigating schooling in Aotearoa New Zealand | New Zealand Council for Educational Research https://www.nzcer.org.nz/research/publications/compass-whanau-pasifika-navigating-schooling-aotearoa-new-zealand

•COMPASS 3: Poipoia ngā tamariki—How whānau and teachers support tamariki Māori to be successful in learning and education | New Zealand Council for Educational Research https://www.nzcer.org.nz/research/publications/poipoia-nga-tamariki

•COMPASS 4: COMPASS: Whānau partnerships with school—patterns and associations with Māori students’ learning | New Zealand Council for Educational Research https://www.nzcer.org.nz/research/publications/COMPASS-whanau-partnerships-with-school

Acknowledgements

In this article, we report on findings from our COMPASS research programme, which is a partnership between Rangahau Mātauranga o Aotearoa | New Zealand Council for Educational Research (NZCER) and Professor Melinda Webber from Waipapa Taumata Rau | The University of Auckland. COMPASS is part of NZCER’s Te Pae Tawhiti Government Grant programme of research, funded through the Ministry of Education. The broader project was funded by a Rutherford Discovery Fellowship, administered by the Royal Society Te Apārangi. We would like to thank all the school communities (ākonga, their kaiako, and whānau) who completed our surveys and allowed us to share their experiences and perspectives in this article. Our thanks also go to Sheridan McKinley who provided critical feedback and support throughout this project, and for her careful review of the outputs.

Dr Melinda Webber is a professor of Māori education at Waipapa Taumata Rau | The University of Auckland.

Dr Melinda Webber is a professor of Māori education at Waipapa Taumata Rau | The University of Auckland.

Dr Mohamed Alansari (corresponding author) is a senior researcher at Rangahau Mātauranga o Aotearoa | New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Dr Mohamed Alansari (corresponding author) is a senior researcher at Rangahau Mātauranga o Aotearoa | New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Email: mohamed.alansari@nzcer.org.nz

Email: mohamed.alansari@nzcer.org.nz

Rāhera Meinders is a lecturer at Waipapa Taumata Rau | The University of Auckland.

Rāhera Meinders is a lecturer at Waipapa Taumata Rau | The University of Auckland.

Dr Jean M Uasike Allen is a senior lecturer at Waipapa Taumata Rau | The University of Auckland.

Dr Jean M Uasike Allen is a senior lecturer at Waipapa Taumata Rau | The University of Auckland.

Nicola Bright is a kairangahau Matua Māori at Rangahau Mātauranga o Aotearoa | New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Nicola Bright is a kairangahau Matua Māori at Rangahau Mātauranga o Aotearoa | New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Renee Tuifagalele is a research officer at The Front Project, Australia.

Renee Tuifagalele is a research officer at The Front Project, Australia.

Sinead Overbye is a kairangahau Māori at Rangahau Mātauranga o Aotearoa | New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Sinead Overbye is a kairangahau Māori at Rangahau Mātauranga o Aotearoa | New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Dr Mengnan Li is a researcher at Rangahau Mātauranga o Aotearoa | New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Dr Mengnan Li is a researcher at Rangahau Mātauranga o Aotearoa | New Zealand Council for Educational Research.