How might research on schools’ responses to earlier crises help us in the COVID-19 recovery process?

CAROL M UTCH

Key points

•Recent disasters and crises in Aotearoa New Zealand, including COVID-19, highlight the need to better understand and prepare for future events.

•Schools play a pivotal role in supporting their communities through these events, but their contribution is not widely acknowledged.

•There is a need for focused pre-event training to ensure that schools are well-prepared for the roles they are asked to take on.

•Once a crisis hits, there is also a need for ongoing support for the multiple roles schools will play during and after the event.

A summary of Carol Mutch’s research into the role of schools in disaster response and recovery highlights the expectations that are placed on schools following a crisis. Her research shows that school staff undertake these extra demands willingly and conscientiously, despite the toll that it takes on their own health and wellbeing. In this article she first outlines the typical process that responses to a disaster or crisis goes through. She then shares some key findings, noting how schools become community hubs, principals become crisis managers, and teachers become first responders. Her final theme is the importance of assisting children and young people to safely process their experiences and provide opportunities to actively contribute towards their own and others’ recovery.

Introduction

COVID-19 took the world by surprise and, on March 25, Aotearoa New Zealand went into Alert Level 4 lockdown with little preparation or understanding of what we might face. We are now back at school, but still surrounded by global uncertainty. As we begin to gather information on school experiences of lockdown, online teaching, and returning to school, what can we take from school responses to earlier crises?

Since I began my study on the role of schools in disaster response and recovery following the Canterbury earthquakes I have expanded my research to include different countries and crisis types. While the contexts might have differed, there was surprising consistency across the settings in terms of what was expected of schools and how they responded. In this summary of my research I want to highlight the findings across four central themes to provide a comprehensive picture of the roles that schools play. The purpose is to ensure that schools are recognised for what they undertake, over and above expectations, in crisis contexts. It is also to suggest how schools might be better supported through and beyond a crisis, such as COVID-19, and whatever we may face in the future.

Between 2012 and 2014, five Canterbury primary schools allowed me to share parts of their post-earthquake response and recovery journeys. I was also able to visit post-bushfire schools in Victoria, Australia. Four strong themes emerged as I interviewed principals, teachers, support staff, parents, and community members, and worked with students on different projects to record their collective stories. The first theme is the place of local schools as the hubs of their communities (see, Mutch, 2016; 2018a, b). The second theme is the way in which the principal’s job changes during a traumatic event from educational leader to crisis manager (Mutch, 2015a, b). The third theme highlights the multiple roles played by teachers from their first response to the ongoing support they provide for students and their families (Mutch, 2015c). The fourth theme suggests the importance of providing children and young people with opportunities to safely process their experiences. This final theme also includes supporting children and young people to take an active role in their own and their community’s recovery (Mutch, 2013a, 2017a; Mutch & Gawith, 2014).

From 2015, I conducted similar research in post-disaster settings in Japan, Vanuatu, Nepal, and Samoa. I was able to test my four themes against these different experiences. While there was local variation, schools still held a central place in community recovery. Principals stepped up to post-disaster leadership roles. Teachers opened their homes and their hearts to students and their families. Children and young people showed courage and resilience as they came to terms with the enormity of the events (Mutch, forthcoming; Mutch & Latai, 2019). I have also gathered insights into school responses to more recent crises (see Mutch, Miles & Yates, 2020). My four original themes resonate across all these settings. There is a growing interest in these findings. They have been shared widely in seminars, and more recently webinars, for principals and teachers in New Zealand, Australia, and Japan. There is little other research that so comprehensively captures the full role of schools and school personnel through the crisis response and recovery cycle.

What is the crisis cycle?

Schools are found in most communities and have historical, social, and cultural ties with the families in their neighbourhoods and beyond. The many roles they play in ordinary and extraordinary times are often taken for granted. Not only are schools places of education, they are often community meeting places. They host many educational, social, cultural, and sporting events. When a crisis hits, they become even more connected to the lives and experiences of local families and communities (Mutch, 2016; 2017b; 2018a, b).

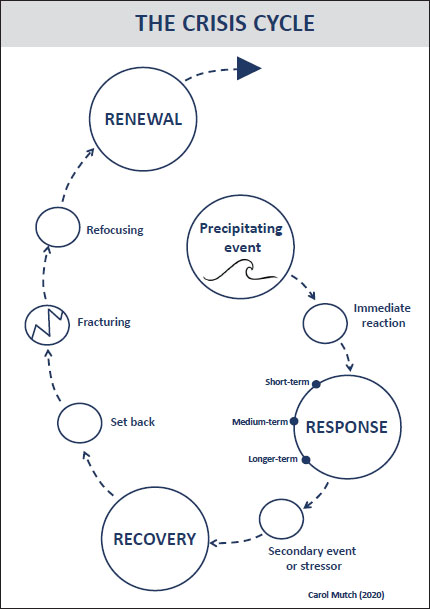

There are many models that outline the processes that communities go through to respond and recover from disasters and crises. New Zealand Civil Defence talks of four phases of emergency management—reduction, readiness, response and recovery (known as the 4Rs).1 The 4Rs are often shown as a neat circle with four even quarters. I feel a more realistic understanding of the nature of the cycle could provide a stronger sense of what to expect in a crisis. While my focus was only on response and recovery, I found that these two phases were far more complex than they appeared in emergency planning documents. I created my own diagram of the crisis cycle to portray more closely what I observed (see Figure 1).

Drawing on my studies and the work of earlier disaster scholars (Drabek, 1986; Gordon, 2004), I tied to convey a cycle that is more elongated and open-ended. The cycle starts with the precipitating crisis event and ends with a sense of renewal. A crisis could be one that is anticipated as in an approaching weather event or completely unexpected as in a terror attack. It could happen in a specific location as in a mine disaster or have a much broader impact as in a pandemic.

Immediate reactions are shock and disbelief. In the short term, we often focus our own safety or the safety of those around us. Next, we might take a scan of the immediate surroundings as we try to make sense of the situation. We might experience a rush of adrenalin where we choose to stay put or leave, known as “fight or flight”. It is in this state of heightened alertness that many heroic acts take place. People find the strength to rescue others, search for survivors, support victims, or keep order until help arrives.

Depending on the type of event and whether it is repeated or ongoing, the response phase begins with attending to the most desperate needs. These needs might be getting medical attention, seeking shelter, or locating basic supplies. Communication and transport links are often disrupted. Our minds turn to worrying about our loved ones and whether they are safe. Amid the chaos and disorganisation, people become dislocated and distraught. In the absence of formal communication, rumours and misinformation abound making the situation even more confusing.

FIGURE 1. THE CRISIS CYCLE

After a time, rescue services arrive and someone takes charge. The chaos becomes a little more ordered. Authorities take stock of the situation and plan what to do next. In the later response phase and early recovery phase, while there might be some antisocial behaviour, such as looting, we often see the best come out in people. This is called the “honeymoon period”. Community members come together to help one another. We hear of generous acts and supportive initiatives that provide heartening stories and generate hope.

Disasters and crises are not one-off events. There will be many repercussions and possibly repeated events. There might, for example, be a tsunami after an earthquake or social and economic disruption following a pandemic. These follow-up events cause further anxiety and distress. Eventually, authorities begin the formal process of recovery. In my diagram, I have tried to convey that the recovery stage is of indeterminate length—and always longer than anyone imagines. The Canterbury earthquakes provide us with a constant reminder of how long and complex the process of recovery can be.

Along the recovery journey, the setbacks and secondary stressors wear people down. The goodwill that was seen in the honeymoon period starts to disintegrate. Bureaucracy becomes tedious and interferes with our ideas of a swift and smooth recovery. Tension starts to build as people feel that some individuals or groups are being favoured over others. The social ties that existed before the event have weakened. Newer social ties are not always as strong. Social cohesion fractures. At one end of the continuum, there might be organisational bickering or political standoffs. At the other end, protests and riots might erupt. At this time, it is important to rebuild a sense of purpose and direction, to keep social order and maintain recovery momentum. At some point, if no further breakdown occurs, the community refocuses and finds a hopeful way forward. Regeneration and renewal can now occur.

What is the role of the school as a community hub in the crisis cycle?

Schools are such an integral feature of our lives and communities that the significance of their role as a community hub is often overlooked. Schools are complex webs of interconnections between places, people, organisations, and wider society. It is not until a crisis occurs, such as a school closure, that people remember how intertwined local schools are with their lives (Mutch, 2016; 2017b).

Like marae, the buildings and facilities take on multiple uses when a crisis strikes. Schools might be used as emergency shelters, relief hubs, communication centres, or a place to locate support agencies. More significantly than the physical support they provide, they offer a sense of safety and security. Whether people come to sleep in the school hall, shower in the physical education block, register with agencies in the reception area or have a coffee and chat in the school library, schools are seen as havens of order and calm. If school buildings are damaged in the event, it doesn’t seem to change the idea of schools as and for communities. Teaching continues, whether in tents, teachers’ living rooms, out in the open, or online. Principals become de facto community leaders. Teachers are seen as people who would “know what to do” even when they are not sure themselves (Mutch, 2015c, 2016; forthcoming).

Disaster agencies and education officials highlight the importance of getting schools up and running. A school in operation signals that there is a return to a semblance of normality. It enables parents to return to work or deal with the after-effects of the disaster. It provides somewhere safe and secure for children and young people to resume their education—even if that is under quite different circumstances. Despite the difficulties in their own lives, principals, teachers, and other school staff are expected to return to work. They come back to trying conditions and without their usual facilities and materials. For years afterwards, schools will still be picking up the pieces of community trauma. It might be children’s unresolved mental-health concerns, the impact of family breakdowns, or community economic decline. Despite these issues, my studies showed that schools continued to be there for their communities. They helped secure necessary resources, services, and funds. They were also places that helped mend the community’s damaged social fabric. They would bring people together for information evenings, and family and community events and commemorations (Mutch, 2016, 2018a, b) long after the event had passed.

“Like marae, the buildings and facilities take on multiple uses when a crisis strikes. Schools might be used as emergency shelters, relief hubs, communication centres, or a place to locate support agencies. More significantly than the physical support they provide, they offer a sense of safety and security.”

How does the principal’s role change during a crisis?

Principals and their leadership teams most often felt unprepared for what they were about to face. While most education systems expect schools to have emergency plans and evacuation drills, these were not necessarily at hand, up to date, well-rehearsed, or appropriate. The reports of how Christchurch schools dealt with the mosque massacre lockdown illustrates a wide variation in responses. In a fast-moving context, principals suddenly move from being educational leaders to crisis managers (Mutch, 2015a, b, forthcoming). Across my study, however, they did not feel that their principal training had provided them with enough understanding of a crisis context. They often fell back on instinct. Instinct usually worked in their favour, but there were examples, in Japan in particular, where lack of foresight had tragic consequences. To provide a framework for principals I undertook an analysis of their actions as crisis managers. My framework (Mutch, 2015a) highlights three attribute groups. The first attribute group is dispositional—what does a principal bring to the role? The second attribute group is relational—how does a principal build strong relationships and networks within and across the school community ahead of any crisis? The third attribute group is contextual—how does a principal manage the multiple complexities when faced with a crisis situation?

A principal’s role in a crisis is constantly changing. Principals need to respond differently at different times. When the event strikes, everyone looks to them. Visibility is important. They have to appear decisive and in control. Once students and staff are rescued, evacuated, and safe, they need to move from “command and control” mode to making sense of what has happened. They use this information to make decisions about what to do next. All the while they need to remain calm and show empathy. This stage often involves negotiation and delegation with their leadership teams and wider staff. I characterise this stage as repeated “zooming in and zooming out”. Principals need to repeatedly gather information about what is going on in the wider crisis context and relate it back to the situation that they are facing.

Because schools are in loco parentis, they also have a duty to keep students’ parents and carers informed. Principals need to keep appraised of communications coming in and then tailoring this information for communications that they send out. As the situation moves from response to recovery, principals can spend less energy on day-to-day crisis management and put more focus on crisis leadership. At this stage, their leadership is characterised by providing a vision of a positive future along with consultation on a plan of how to get there. At the same time, they need to keep an eye on the wellbeing of their staff. One central feature in my study, however, was that principals rarely looked after their own wellbeing—something that education agencies need to factor in to post-crisis support.

A further analysis of the principals in my study revealed that they simultaneously kept adjusting their own roles as well as making good use of their leadership teams (Mutch, 2015b). Principals noted that having prepared for any crisis situation, even if it was unrelated, was better than no preparation. It meant that some scenarios had been discussed and roles assigned prior to a crisis event. If leadership teams and wider staff had helped design protocols and procedures, they had more confidence to step up when they were needed. There is a detailed checklist in Mutch (2015b) which suggests tasks to be considered and allocated across the crisis cycle, including pre-event preparation as well as during the event itself. The tasks are set out in three columns—for the leader, the leadership team, and the wider organisation. Schools might find that table (too large to reproduce here) useful in their own crisis-preparedness planning.

How does the role of the teachers change during a crisis?

What stays with me from my research on teachers is a statement made by a parent: “All these teachers are quiet heroes… there are teachers here that have lost their homes and some of them are living in the same situation as we are and they come to work and they get on with it.” In many of the settings I studied, teachers, principals, and other school staff were also victims of the event or severely affected by it. They lost loved ones, homes, and possessions. They were coming to school with a positive focus on their students despite the myriad of problems that awaited them at home. If the event happened when school was in session, teachers became first responders, in some cases putting their own lives at risk. Once students were safe and settled, teachers stayed with them until someone came to claim them—and if no-one came, teachers ensured that students were taken care of (Mutch, 2015c; forthcoming).

“A principal’s role in a crisis is constantly changing. Principals need to respond differently at different times. When the event strikes, everyone looks to them. Visibility is important. They have to appear decisive and in control. Once students and staff are rescued, evacuated, and safe, they need to move from ‘command and control’ mode to making sense of what has happened. They use this information to make decisions about what to do next. All the while they need to remain calm and show empathy.”

In the time before schools recommenced, teachers found creative ways to keep up social contact with their classes and support them and their families. When schools reopened, teachers had already been there—repairing, tidying up, finding resources, and preparing ways to welcome students back to school. In the early days, many students did not come back or their attendance was intermittent, so teachers needed to be flexible and adaptable.

As schools settle into a recovery routine, teachers need to find a balance between the normal business of schooling, and dealing with students’ emotional, social, and psychological needs (Mutch & Latai, 2019). Across all the settings, appropriate counselling support was either non-existent, limited, or stretched thin. Teachers felt that they needed a better understanding of what to expect and also how to identify and support students with trauma. They also needed guidance on when it was time to return to the regular curriculum. While providing pre-service or in-service training for teachers on what to expect in a crisis was a recommendation from my research (Mutch, 2015c), I have not yet seen this suggestion taken up.

The toll of supporting students in a fluid, constantly changing set of circumstances as well as managing their own home and family issues finally takes its toll. While school leaders and teachers tried to support each other, the stress eventually led to a decline in their physical and mental wellbeing. In three settings (Japan, Samoa, and New Zealand), bureaucratic decisions around school closures, amalgamations and the relocation of schools and staff added to the stress teachers were already under (Mutch, 2017b; forthcoming). Yet when the medals were given out and the citations read, teachers, school leaders, and support staff were overlooked. They were simply considered to be doing their job.

How do we support children and young people during and after a crisis?

One of my initial reasons for undertaking my research after the Canterbury earthquakes was to support schools to compile a record of their experiences. This record would be available for them, their communities, and future generations. I found funding to conduct and manage the projects. Schools agreed that their stories could be forwarded to the National Library and Archives New Zealand. What I hadn’t anticipated was the creative ways in which schools would take up my offer and how therapeutic the exercise was for everyone involved (see Mutch, 2013a; Mutch & Gawith, 2014).

I came to understand more about the importance of post-trauma emotional processing for children. By using a range of safe practices, such as arts-based activities, storying, or guided discussions through picture books or puppets, children can begin to make sense of what has happened. They come to realise that they are not alone in how they feel. They start to absorb the event into their own personal histories. In this way, they gain a measure of emotional distance from the event so they can begin to heal (Gibbs et al., 2013; Mutch & Latai, 2019).

Many children will exhibit signs of distress or unusual behaviour in the early aftermath. They will experience clinginess, bedwetting, or anxiety, but most will recover over time. For those who have severe symptoms, bringing in trained support is necessary. A lesson we learned from the Canterbury earthquakes is that mental-health needs were not given the attention they were due until the establishment of the Mana Ake programme.2 Is this something we need to consider nation-wide as the after-effects of COVID-19 set in?

What I also came to understand was the usefulness of engaging children in projects that took children out of themselves and helped them focus on others. Being empowered to make decisions and work collaboratively for others proved beneficial in both the short (Mutch, 2017a) and long term (Mutch, Miles & Yates, 2020).

While, of course, we understand that children and young people can be vulnerable in crisis contexts, they are not passive victims. They have a right to participate in issues that relate to them. We need to listen to their views and engage them in suitable crisis recovery activities. When I visited post-bushfire schools in Victoria, students proudly showed the ways they had contributed to the redesign of their new schools. I was shown indoor gardens, covered basketball courts, adventure playgrounds, and running tracks. While children in Christchurch did get a say in the Margaret Mahy playground, in terms of rebuilding schools, no-one thought to ask children what they wanted. It was up to the Student Volunteer Army to show what young people can do if you give them the chance (Mutch, 2013b). I think that there are lessons here that we still need to learn going forward.

What can we take from this research to help us as we move through the COVID-19 levels?

As I write this, the Prime Minister is announcing that we are moving to Alert Level 1. Many of us will still be wondering how we arrived here so quickly. However, as she made clear, we are not out of the woods. So, what can schools take from my prior crisis research? First, in terms of the crisis cycle—recovery will take longer than you expect. The path ahead will have setbacks. We must try to anticipate them and be prepared to be flexible and responsive. Secondary stressors, such as economic decline and social distress, will have an impact on our families and our students. We need to plan now for how to meet the physical and emotional needs our students will display. There will be social fracturing—it might be within the school, community, locally, or nationally. If we know that this is to be expected, we can try not to take matters personally or escalate tensions further. This phase will pass. Schools can play a part in helping their communities refocus. They can bring them together in ways that rebuild the social ties that had become frayed by social distancing or fear of community transmission. Schools can also model how to move forward with purpose and hope.

“By using a range of safe practices, such as arts-based activities, storying, or guided discussions through picture books or puppets, children can begin to make sense of what has happened. They come to realise that they are not alone in how they feel. They start to absorb the event into their own personal histories. In this way, they gain a measure of emotional distance from the event so they can begin to heal.”

Principals could reflect, individually and collectively, on the experience of leading schools through the COVID-19 alert levels. What worked well? What could have been done better? What have they learned about themselves in terms of their dispositional, relational, and contextual attributes? How well did they use the potential within their teams, schools, communities, and networks? Where are their leadership strengths, individually and collectively, and where might improvements be made? How can we ensure that principals receive the training and support that they need to take on and manage crisis leadership roles without any detriment to their own health and wellbeing?

Similarly, how do we help teachers reflect on what they have experienced and achieved? How do we assist them to build on the positives and learn useful lessons from the not-so-positives? How do we ensure that when they take on the multiple roles expected of them, the agencies and support services that they need are sufficiently funded, staffed, and responsive? How do we ensure that the health and wellbeing of teachers is prioritised? How do we acknowledge the extra load that all school staff carry in difficult times? How do we show that we value them? How do we, as a society, say “thank you”?

And the children and young people in our care—what can we learn from this research to support them? It helps to understand how trauma affects students, how to recognise the signs, how to provide support, and where to seek help when things are outside our expertise. It is useful to find ways to help our students process their emotions and experiences. This is not something that has gone unnoticed in response to the pandemic. There is a range of resources for teachers available, especially in the form of educational websites. Two New Zealand sites that come to mind are Te Rito Toi3 and The Education Hub.4 They have picked up the challenge of providing accessible resources for teachers and students in the COVID-19 context. They provide activities and lessons that focus on using the arts for emotional processing, dealing with anxiety, and building resilience. Finally, it is helpful to get our children and young people to think beyond themselves, to find ways to help others, to contribute positively to their own and the country’s recovery process. In this way we help them and ourselves move forward with critical hope.

Notes

References

Drabek, T., 1986. Human system responses to disaster: An inventory of sociological findings. Springer-Verlag. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-4960-3

Gibbs, L., Mutch, C., O’Connor, P., & MacDougall, C. (2013). Research with, by, for, and about children: Lessons from disaster contexts. Global Studies of Childhood: Actualisation of children’s participation rights, 3(2), 129–141. https://doi.org/10.2304/gsch.2013.3.2.129

Gordon. R. (2004). The social system as a site of disaster impact and resource for recovery. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, 19(4), 16–22.

Mutch, C. (Forthcoming). High expectations, low recognition: the role of principals and teachers in disaster response and recovery in the Asia-Pacific. In H. James, (Ed.), Risk, Resilience and Reconstruction: Science and Governance for Effective Disaster Risk Reduction and Recovery. PalgraveMcMillan.

Mutch, C. (2018a). The place of schools in building community cohesion and resilience: Lessons from a disaster context. In L. Shellavar & P. Westoby (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of community development research (pp.239–252). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315612829-16

Mutch, C. (2018b). The role of schools in helping communities cope with earthquake disasters: The case of the 2010–2011 New Zealand earthquakes. Environmental Hazards, 17(4), 331–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/17477891.2018.1485547

Mutch, C. (2017a). Children researching their own experiences: Lessons from the Canterbury earthquakes. Set: Research Information for Teachers (2), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.18296/set.0077

Mutch, C. (2017b). Winners and losers: School closures in post-earthquake Canterbury. Waikato Journal of Education, 22(1), 73–95. https://doi.org/10.15663/wje.v22i1.543

Mutch, C. (2016). Schools as communities and for communities: Learning from the 2010–2011 New Zealand earthquakes. School Community Journal, 26(1), 99–122.

Mutch, C. (2015a). Leadership in times of crisis: Dispositional, relational and contextual factors influencing school principals’ actions. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 14(2), 186–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2015.06.005

Mutch, C. (2015b). The impact of the Canterbury earthquakes on schools and school leaders: Educational leaders become crisis managers. Journal of Educational Leadership, Policy and Practice, 3(2), 39–55.

Mutch, C. (2015c). “Quiet heroes”: Teachers and the Canterbury earthquakes. Australasian Journal of Disaster and Trauma Studies, 19(2), 77–86.

Mutch, C. (2013a). “Sailing through a river of emotions”: Capturing children’s earthquake stories. Disaster Prevention and Management, 22(5), 445-455. https://doi.org/10.1108/DPM-10-2013-0174

Mutch, C. (2013b). Citizenship in action: Young people’s responses to the Canterbury earthquakes. Sisyphus: Journal of Education, 1(2), 76–99.

Mutch, C., & Gawith, L. (2014). The role of schools in engaging children in emotional processing of disaster experiences. Pastoral Care in Education, 32(1), 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2013.857363

Mutch, C. & Latai, L. (2019). Creativity beyond the formal curriculum: Arts-based interventions in post-disaster trauma settings. Pastoral Care in Education, 37(3), 230–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2019.1642948

Mutch, C., Miles, J., & Yates, S. (2020). “River of emotions”: Reflecting on a university–school–community partnership to support children’s emotional processing in a post-disaster context. In R.M. Reardon & J. Leonard (Eds.), Alleviating the educational impact of adverse childhood experiences: School–university–community collaboration. Information Age Publishing.

Carol Mutch is a professor in critical studies in education at The University of Auckland. Her research into the role of schools in disaster response and recovery has earned her a 2020 University of Auckland Research Excellence medal. She is the author of numerous books and journal articles and her contributions to education and educational research have been recognised with national and international awards. She is currently the Education Commissioner for the New Zealand National Commission for UNESCO.

Carol Mutch is a professor in critical studies in education at The University of Auckland. Her research into the role of schools in disaster response and recovery has earned her a 2020 University of Auckland Research Excellence medal. She is the author of numerous books and journal articles and her contributions to education and educational research have been recognised with national and international awards. She is currently the Education Commissioner for the New Zealand National Commission for UNESCO.

Email: c.mutch@auckland.ac.nz