Improving engagement and achievement for Year 11 Māori and Pasifika students

CELIA FLECK

I am passionate about continually looking for ways to improve outcomes for students. I believe in the importance of being a connected educator, and in the responsibility we have to share our stories and learnings with one another. My involvement in the Sport in Education project has meant that I have been extremely fortunate to work alongside colleagues in my own school with whom I would not normally work. I have also been able to work with colleagues from other schools around New Zealand, and a fantastic team of researchers at NZCER. I am pleased to share this story in the hope that it may spark an interest, and provide a platform for others to explore similar approaches in their own teaching and learning environment.

Introducing the Sport in Education Project

My school was chosen to take part in the Sport in Education project funded by Sport New Zealand. The aims of the project are improved academic outcomes, improved positive social outcomes, and increased numbers of young people enjoying and involved in sport. The project is in its third year in 2015.

When I first heard about the project I saw it as an opportunity for our school to explore some innovative practice to improve academic outcomes for our target groups—that is, males, Māori, and Pasifika students. We have large numbers of students participating in and enjoying success in sport and it seemed a perfect opportunity to use this context to improve achievement and engagement for our priority learners. It was also an exciting opportunity for curriculum areas to collaborate and share good practice around effective teaching pedagogies.

Our main Sport in Education priorities at Aotea have included building a strong sense of community, a focus on raising achievement for target students, and provision of a responsive curriculum. Creating an integrated sports class was seen as one way of building stronger learning relationships for Year 11 students who had been identified as at risk of not gaining an NCEA qualification, and creating a more coherent learning programme for them.

A focus on teaching as inquiry

Creating an NCEA Level 1 sports studies class meant students could take part in learning that was set in sports contexts. We thought this was a good idea because we noticed from our school-wide data that a large group of mostly male Māori and Pasifika students were at risk of not achieving NCEA Level 1, but were achieving well in physical education.1 Students applied to be in the class, and were selected in consultation with teachers and whānau. Students who were at risk of not gaining Level 1 NCEA were our priority, but higher achieving students were not excluded. The ratio of male/female students in the class was 2:1 and 21 of the 23 students identified as Māori or Pasifika.

We wanted to see if working in this class could help all the students achieve NCEA Level 1 literacy and numeracy requirements by the end of the year, and increase the number of endorsements they got in NCEA English, mathematics, and physical education. We also wanted to ensure that all these students were still at school at the end of the year, and were motivated to return for year 12 studies. Once we were clear about our aims, it became easier to plan an overall strategy to gather evidence of about how successful we had been.

What we did

In the sports studies class the students worked together for 12 hours each week. Another health and physical education teacher and I taught them for 6 hours each. I taught a mathematics/physical education combination. The other teacher taught an English/physical education combination. We had an hour together each week for planning and coordination. We also met regularly with teachers from the English and mathematics department to support us in the delivery of these curriculum areas. Sport was the context in which we delivered the curriculum across the three learning areas.

We wanted to see if working in this class could help all the students achieve NCEA Level 1 literacy and numeracy by the end of the year, and increase the number of endorsements they got in NCEA English, mathematics, and physical education.

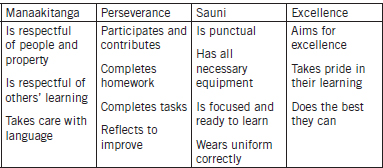

We designed a broad, deep-learning programme where we experimented with using learning contexts with a sports focus. Each term we included a focus on one of the school-wide expectations developed as part of the PB4L school-wide initiative.2 Figure 1 summarises these expectations (note that Sauni is a Samoan concept that broadly translates as being ready for action). The programme we designed also made links between the curriculum areas, all within a sports context.

FIGURE 1. SCHOOL-WIDE EXPECTATIONS AT AOTEA COLLEGE

Figure 2 shows the NCEA achievement standards that were used to assess learning in the integrated programme we had designed. Learning pathways in mathematics and English were personalised in consultation with heads of department, students. and whānau.

Term 1 involved a focus on Manaakitanga. This school-wide expectation aligned well with the focus on interpersonal skills in physical education, and was a good platform for setting up the expectations within the class. Rugby was the common theme that linked the curriculum areas.

•In mathematics students were learning about number (fractions, decimals, percentages, exchange rates, GST) and exploring budgeting and saving to attend the 2015 Rugby World Cup.

•In physical education students were working to improve their performance in flag (or tag football—flag is a game similar to rugby league or union, but instead of making a tackle you rip a Velcro flag off the opposition’s shorts).

•In English students were studying a novel about a boy trying to fit in to a new school and striving to make the first XV rugby team.

In term 2 we used the context of basketball, and the school expectation of perseverance, to link together the learning in the three curriculum areas.

•In mathematics students used the context of the basketball free throw to investigate a situation involving elements of chance.

•In physical education the focus was on biophysical concepts; students were developing their understanding of exercise physiology, anatomy, and biomechanics with the aim of using this knowledge to analyse and improve skill performance in basketball.

•In English students were completing a film study of Coach Carter (a movie about an American high school basketball coach). The theme of perseverance was used throughout the year in English to Explain significant connections across texts (AS90852); students collected examples of athletes demonstrating perseverance in novels, films, and real life.

FIGURE 2. ASSESSMENT OPPORTUNITIES ACROSS THE THREE CURRICULUM AREAS

| Mathematics | English | Physical Education |

| All students were assessed against:

91026 v3 Apply numeric reasoning in solving problems

91030 v3 Apply measurement in solving problems

91032 v3 Apply right-angled triangles in solving problems

91035 v2 Investigate a given multivariate data set using the statistical enquiry cycle

Students were assessed against ONE of the following:

91027 v3 Apply algebraic procedures in solving problems

OR

91029 v3 Apply linear algebra in solving problems

Some students were assessed against:

91037 v4 Demonstrate understanding of chance and data |

All students were assessed against:

90855v2 (1.7) Create a visual text

90852v2 (1.8) Explain significant connection(s) across texts, using supporting evidence

90854v2 (1.10) Form personal responses to independently read texts, supported by evidence

All students were assessed against at least one external standard:

90849v3 (1.1) Show understanding of specified aspect(s) of studied written text(s) using supporting evidence

90850v3 (1.2) Show understanding of specified aspect(s) of studied visual or oral text(s) using supporting evidence

90851v2 (1.3) Show understanding of significant aspects of unfamiliar written text(s) through close reading using supporting evidence

Some students were assessed against:

Literacy: US 26622 (v2) Write to communicate ideas for a purpose and audience

Literacy: US 26624 (v2) Read texts with understanding

Literacy: US 26625 (v3) Actively participate in spoken interactions |

All students were assessed against:

90962v3(1.1) Participate actively in a variety of physical activities and explain factors that influence own participation

90963v3 (1.2) Describe the functions of the body as it relates to the performance of physical activity

90964v3 (1.3) Demonstrate quality of movement in the performance of a physical activity

90965v3 (1.4) Demonstrate understanding of societal influences on physical activity and the implications for self and others

90966v2 (1.5) Demonstrate interpersonal skills in a group and explain how these skills impact on others

|

| Integrated Assessment task across English and physical education (all students): 90053v5 (1.5) Produce formal writing and 90969v3 (1.8) Take purposeful action to assist others to participate in physical activity |

In term 3 the Commonwealth Games were happening in England and we linked this context to our learning, as well as our school expectation of excellence.

•In physical education students took action to plan and run an “Aotea Games” event for the Year 10 cohort; this involved opening and closing ceremonies, and throughout the day students competed in physical activity events—netball, ki o rahi, sevens rugby, dodgeball, rowing—as well as some non-physical events, including pavement art, general knowledge quiz and a technology challenge. This gave the Year 11 students a powerful experience of making a contribution to the wider school community.

•In English students were learning about how to construct a piece of formal writing and, at the conclusion of the Aotea Games, they wrote about it for the purpose of the school magazine.

•We used this context to design an integrated NCEA assessment task. We combined the physical education AS90969 Take purposeful action to assist others to participate in physical activity with the English AS90053 Produce formal writing. The work they did in planning, implementing, and then writing about the Aotea Games provided evidence for achievement in the two achievement standards.

•Students also collected data from the indoor rowing event to support their learning about the statistical enquiry cycle, and work towards mathematics AS91036 Investigate bivariate numerical data using the statistical enquiry cycle.

In term 4 we focused on our school expectation Sauni. This meant preparing students for external English and mathematics examinations.

During every class, we used sporting analogies to reinforce class culture and expectations, and to contextualise the teaching and learning. For example, the structure of a mathematics lesson was likened to a training session, which included a warm up, skills practice, and a modified game. Assessments were referred to as “game day” and leading up to this we would participate in a number of “pre-season games”. We kept up a strong focus on being a “team”, although as the year went on students began to refer to themselves as a family or whānau. We found that the whānau environment which evolved was hugely valuable to some students in providing stability and we incorporated a strong element of pastoral care into our interactions with the students. Feedback from students was that they felt that the positive learning relationships within the class contributed more to their success than the sports context. Consistent contact with fewer teachers with shared messages and expectations, and greater whānau contact, also contributed to the success of this approach.

We took deliberate actions to work with students’ whānau throughout the year, meeting with their whānau once a term. The initial meeting was to find out what they knew (or thought they knew) about the approach we were taking, and to answer any questions. We discovered at this meeting that there were several gaps in people’s understanding of NCEA, and so we were also able to offer ongoing support in this area. My colleague and I worked together to run the parent–teacher conferencing for our students, which enabled a lengthier conversation about their son or daughter. This conferencing opportunity was well attended by students and their whānau, largely because of our consistent contact throughout the year.

We believe that culturally responsive pedagogies underpinned our teaching and learning approach. These included:

•supporting good academic decision making

•involving whānau

•recognising diversity of learning—one size does not fit all

•knowing our students and whānau

•having high academic expectations.

The evidence we gathered

At the end of term 1 the project team met for a review. The English teacher noticed that the work the students were producing and the results gained in English in term 1 were above what she would have predicted from their Year 10 results. She believed that we had “created a myth” whereby students believed that it was going to be easier to learn and achieve in sports studies, and therefore it was. We surveyed students to ask them what it was about sports studies that was having a positive impact on their learning and achievement. This was some of the feedback:

•“We have similar goals and attitudes towards our learning, everyone wants to achieve, we are more engaged in our learning because it’s in a sports context that we understand.”

•“Another positive is the way work and assessments are given, in a sporting context. With everyone being into sports, it makes work more fun and easier to understand.”

We noticed how the students’ confidence increased as the year went on, and so did they. Students enjoyed the team philosophy, even though this became a bit competitive between the boys and the girls at times. The sport-related resources made it easier for them to make connections to, and be interested in, their learning. The routine use of “team” and “coaching” metaphors, combined with the creation of a tight whānau group, also served to keep them on track.

At the end of the year the class completed a piece of writing for English that was a letter to myself and my colleague teaching the class. What came through very strongly from the students was the importance of building a positive relationship with their teachers in contributing to their success.

•“Positive relationships mean people are not afraid to ask for clarification.”

•“Another positive aspect of this class was having two teachers who actually cared about our learning and achievements we did in and outside of the classroom.”

•“The positives I have experienced in this course is that you get to build a relationship with the teachers, because honestly, if I don’t know the teacher or do not work well with them then I will not try my best for them.”

The English teacher noticed that the work the students were producing and the results gained in English in term 1 were above what she would have predicted from their Year 10 results. She believed that we had “created a myth” whereby students believed that it was going to be easier to learn and achieve in sports studies, and therefore it was.

The school created a “matched” group of students so that we could compare data for our class with other similar students in the school.3 This matched group was compiled by selecting “like-for-like” students based on gender, ethnicity, and asTTle data.

•At the end of the year we found that attendance was slightly higher for our class (87 percent) than for the matched group of Year 11 students (85 percent).

•All the sports studies students were still at school at the end of the year. Two had left from the matched group without achieving NCEA Level 1.

•Referrals for pastoral issues were almost halved compared to those for the same students in 2013, whereas pastoral entries for the matched group more than doubled.

•All students in the sports studies class achieved NCEA Level 1 literacy, compared to 21/23 in the matched group. They were also more successful in gaining NCEA Level 1 numeracy (22/23 compared to 17/23 for the matched group) and in gaining the 80+ credits required for an overall NCEA award at Level 1 (sports studies class 20/23; matched group 15/23).

•Almost half the class (11/23 students) gained endorsements for physical education (2 with excellence and 9 with merit), and two students gained merit endorsements in mathematics. Five students from sports studies gained a Level 1 NCEA merit certificate endorsement compared to three students in the matched group.

The results that really interested us emerged when we looked specifically at the patterns for Māori and Pasifika students in the two groups. When we looked at the integrated assessment task results we found that in English 50 percent (5/10) of Māori students in sports studies were successful compared with 35 percent (13/37) in other English classes, and 73 percent (8/11) of Pasifika students were successful compared with 38 percent (6/16) in other English classes. In physical education 100 percent of sports studies students were successful compared with 75 percent of Māori and 80 percent of Pasifika students from the other physical education classes. This integrated task was also significant for male achievement with only 75 percent of males in other physical education classes achieving.

Combining the two achievement standards placed more value on the assessment task. For many of the students who did not achieve the physical education standard, this was due to a lack of work completion and not submitting the written component of the task. For the students in sports studies the written component became more valuable and therefore students saw it as more important that they complete it. Writing a formal piece for the school magazine about something that the students had been involved in was more meaningful and relevant to them and they were more engaged in the task.

The results that really interested us emerged when we looked specifically at the patterns for Māori and Pasifika students in the two groups. When we looked at the integrated assessment task results we found that in English 50 percent (5/10) of Māori students in sports studies were successful compared with 35 percent (13/37) in other English classes, and 73 percent (8/11) of Pasifika students were successful compared with 38 percent (6/16) in other English classes.

What we learned and what we’ll try next

We found it extremely valuable that the time with these students enabled us to get to know them and their whānau well, and therefore create a supportive learning environment, that contributed to increased engagement and achievement.

Creating the integrated course and working towards NCEA assessments in the non-physical education parts was a steep learning curve for two physical education teachers. Having one hour per week set aside to meet with each other to plan, reflect and review was hugely valuable. One thing that did not work so well was that the English and mathematics teachers who were also in the project team were not teaching NCEA Level 1 in 2014. This meant that we were not part of valuable conversations that often take part in departments before teaching a particular unit, during the teaching of it, and in reviewing it; and therefore there was not the same sharing of resources or teaching practices that occurs when teachers do collaborate in this way. This is a change we have made for 2015, where we not only have the support of a lead teacher from each department but that we are part of the team of Level 1 teachers within each of those departments and have increased access to knowledge, experience, and resources.

The 2:1 male:female ratio made it very difficult to ensure that we didn’t have a learning environment dominated by the boys. In 2015 we ensured that we had an even gender balance in the class.

Teaching the course for the second time we are able to strengthen many aspects of the course and we now have a better idea of how to integrate internal assessments. Following this study, we aimed to create more integrated assessment tasks.

Conclusion

I am very passionate about the journey that the Sport in Education project has taken me on and the possibilities that have been opened up for cross-curricular collaboration and breaking down our siloed subject areas in secondary schools. The context in which this has taken place has been important. What has been equally important, if not more so, is whakawhanaungatanga—building relationships and relating to others. This has come through strongly in the feedback from students but it has also been a critical success factor in working with colleagues from other curriculum areas. A cross-curricular approach is an opportunity available to all teachers no matter what context or curriculum area. I would encourage all interested teachers to think about the following.

1.Identify a colleague in another curriculum area who you know you could work well with and who would be agreeable to trialling a cross-curricular approach—open up a dialogue with them and start looking for links between your curriculum areas, then start planning.

2.How well do you know your learners? How can you get to know them better?

3.How can you recontextualise what you are currently doing to better suit your learners, and better link to other curriculum areas?

4.What kind of support would you need to gather evidence? What data might you look at to track whether, and how you know you are making a difference? How might you communicate this progress with your school community?

Notes

Celia Fleck is Head of Department, Health and Physical Education at Aotea College, a position she has held for 6 years. Celia is the Sport in Education project leader at her school. She is passionate about continually looking for ways to improve outcomes for students.

Celia Fleck is Head of Department, Health and Physical Education at Aotea College, a position she has held for 6 years. Celia is the Sport in Education project leader at her school. She is passionate about continually looking for ways to improve outcomes for students.

Email: fl@aotea.school.nz