Commentary

Revitalisation, relationships, resources: Assessment 3Rs for New Zealand teachers

Jenny Poskitt

https://doi.org/10.18296/am.0034

Introduction

Exciting developments for New Zealand education have provided opportunities recently for teachers and other educators to express their professional aspirations in assessment. Since the New Zealand Government announced that National Standards reporting was no longer required, and that a review of the National Certificates of Educational Achievement (NCEA) would occur, many teachers have been uncertain about assessment requirements. Although some schools have seized the opportunity for innovation, others have been hesitant for fear of unwittingly neglecting assessment for accountability requirements. This state of ambivalence is a contrast to the tradition of explicit commitment to assessment for learning (Chamberlain, 2018; Poskitt, 2014) and previous clarity about the direction of assessment, as seen in the Position Paper on Assessment (Ministry of Education, 2011). Moreover there was an 8-year commitment to providing Assess to Learn (AtoL) professional development (Poskitt & Taylor, 2009), to build and respect teachers’ professionalism in assessment.

The mantle of fostering teachers’ professionalism through strong relationships across the education sector and relevant stakeholder groups, and the provision of timely professional learning opportunities and pertinent resources to build assessment capability, is experiencing a revival through the recent establishment of the New Zealand Assessment Institute (NZAI). This commentary article explains the NZAI, why it was established, its provision of an assessment seminar series for educators and the effects of those seminars on educator thinking and their intended professional practice.

NZAI

NZAI widely represents education sector and stakeholder personnel through its executive committee and broader membership, with members including academics, professional-development facilitators, the New Zealand Council for Educational Research, teachers, and principals, as well as personnel from government agencies such as the Education Review Office (ERO), Ministry of Education, and New Zealand Qualifications Authority. Implied earlier, the vision of NZAI is to develop partnership networks across the education sector and education stakeholders, and build assessment capability. As an independent organisation, NZAI also seeks to advocate for quality assessment. Established in 2018, NZAI set up a website (www.nzai.org.nz), joined over 250 members and delivered an assessment seminar series, “Rethinking assessment in Aotearoa/New Zealand”, in mid-April. Feedback themes arising from participants at these assessment seminars is the focus of this commentary.

NZAI Rethinking Assessment in Aotearoa/New Zealand seminar series

The Rethinking Assessment in Aotearoa/New Zealand seminar series occurred in Christchurch, Wellington, and Auckland on consecutive days in the April 2018 school holidays. The format of the seminar days comprised two to three keynote speakers, three opportunities to attend teacher-led workshops (sharing innovative practice in assessment), and interactive discussion sessions. Two keynote speakers addressed each of the three seminar days. The first of these keynote speakers provided an overview of the history of educational assessment in New Zealand and its central focus on empowering teachers and learners in classroom-based assessment, particularly assessment for learning (Chamberlain, 2018). These endeavours were due, in large part, to trailblazers in assessment research, such as Terry Crooks, and key personnel in the Ministry of Education; in conjunction with systematic professional development (AtoL). Chamberlain also challenged attendees with ideas for moving forward, such as optimising digital affordances (Chamberlain, 2018). The second keynote speaker, who addressed the three seminar audiences, spoke about the value of moderation processes for empowering teachers (Smaill, 2018). By reflecting on a range of evidence gathered to demonstrate student achievement, and engaging in inquiring conversations with colleagues, teachers’ gain clearer understandings through moderation not only of assessment expectations, but also of curriculum and pedagogical strategies. That assessment (moderation) could be a vehicle for informing effective pedagogical approaches to deliver curriculum was a valuable insight for some seminar attendees. The Wellington and Auckland seminars had different, additional third keynote speakers who signalled innovative directions that national qualifications were taking (Poutasi, 2018), and the need to challenge our assumptions and thinking about the purpose of assessment (Ings, 2018).

School-led workshops were another feature of the seminars. In these sessions, teachers presented their school experiences of innovative practices in assessment. Innovations ranged from evolving digital platforms for managing and communicating classroom-based assessment data, to integrating secondary school subjects and project or portfolio-based assessments. Other sessions considered ERO evaluation expectations, tools such as learning progressions frameworks, the Progress and Consistency Tool (PaCT), and how these resources helped teachers to ascertain student progress, determine pertinent interventions or subsequent teaching, and report progress to parents and whānau.

Having provided background to the content and structure of the NZAI assessment series, attention now turns to the critical topic of the impact of the seminars on delegates’ thinking and professional practice.

Delegate thinking at the seminars

What influence did these sessions have on delegates’ thinking and intended subsequent practice? Discussion group opportunities allowed delegates to share and clarify understandings with other participants, and subsequently to record their responses to three questions:

•What has the day caused you to think about in relation to assessment and learning?

•What do you intend to do differently in your classroom, school, or Kāhui Ako?

•How would you like NZAI to help you solve those issues?

The author collated responses to the three questions for each seminar location (N = 1,250 responses; 3Q x 412 people responses). Inductive content analysis followed. Hsieh and Shannon (2005, p. 1,278) define content analysis as a “systematic classification process of coding and identifying themes and patterns”. In the case of identical phrases from different respondents, aggregation occurred, for example, “more workshops like this one (15)”. Phrases containing similar ideas but different wording clustered together. For example, in the theme “purposeful assessment” similar ideas included, “re-evaluate the why and what of assessment”, “what is necessary versus what is done in assessment”, “how can we better match the things we assess to the values we believe in?” The phrase clusters were subsequently analysed to ascertain possible labels for themes. Theme labels derived from the language respondents used. These themes were subsequently compared across seminar locations and where the same themes occurred in at least two seminar locations, they were included for discussion in this article. Finally, more abstract level categories were derived from themes across the three questions (refer to Table 1).

The next section explores delegate responses.

1.Reflections about assessment and learning. Common themes arose across the three seminar locations. Explanations of eight themes follow; the first five of which were common to the three seminar locations, and the last three themes arose across two locations.

a)Purposeful assessment. Respondents who wrote in relation to this theme realised that they undertook some unnecessary assessments, often out of misperception of requirements or fear of lower levels of professionalism if they had inadequate amounts of evidence related to student achievement. They referred to the importance of gathering only relevant assessment intended for use primarily to guide teaching and learning, or for reporting purposes, e.g., “assessment should be used to inform—not as a tool to compare and make people accountable”. Others mentioned the need for balance—sufficient information to make transparent and well-informed decisions— without overloading students or themselves, e.g., “balance between the right amount of assessment without over-assessing”. The seminar day provided attendees with greater clarity and confidence about what mattered in assessment, and, therefore, the fundamental purpose of assessment.

b)Reviewing current practice. Reflections on current practice revealed the likelihood of discarding some activities and retaining others of value for current or future teaching and learning. In other words, rationalising assessment practices to focus on important or highly useful information. Some respondents grappled with devising a framework or set of guiding principles to influence a review of current practice, e.g., “I am not sure where to start to review our current assessment and learning programmes”. Other respondents indicated an intention to adopt practices presented at the seminar, for example, “Different people’s perspectives and examples from schools have given me time and space to think about where to next in terms of assessment and learning at my school”.

c)Use of learning progressions. Some respondents viewed learning progressions as frameworks for guiding their assessments (a reference point against which to make judgements) and clarifying achievement expectations at particular Year levels, especially with the recent removal of National Standards reference points. For some respondents, the learning progressions helped inform current and future student learning. Others expressed concerns about using learning progressions owing to confusion about appropriate interpretation and adaptation of them—how legitimate was it to adjust learning progressions to localised contexts or for ease of child use? Or, should instrumental integrity and validity be respected by only using the nationally derived versions of the learning progressions?

d)Moderation. Intentionally implementing, or supporting, moderation processes to deepen teachers’ understandings in curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment were commented on by respondents across the three seminar locations. Shared language, vision, and tool use were seen as additional desired outcomes from moderation conversations.

e)Trans-disciplinary assessment. In this theme, respondents referred to various ways of combining or integrating subject matter, for example, through project-based learning, as well as more streamlined assessments, from which judgements could be made about progress and achievement in multiple subject areas. In a few cases, respondents included attention to competencies, capabilities, or skills that spanned several subject areas.

f)Learner involvement in assessment. How to encourage more student voice in assessment was occupying the thinking of many respondents—in terms of increasing student agency in assessment, developing assessment-capable students, encouraging students to shape assessment requirements, and making assessment more relevant for students. Illustrative quotes include, “how are we co-creating success criteria with our learners?” “Perhaps we still lack student voice—an area for development”.

g)Use of assessment for learning strategies. Respondents mentioned the importance of listening to students during the learning and assessment process, noticing details of what students were doing, and realising that assessment was part, not the end, of the learning process. For teachers of secondary school students, realising that summative assessments tended to restrict students’ learning through their focus on collecting credits rather than deepening learning. The challenge for teaching senior students was to prioritise and enhance learning strategies, rather than just outcomes of learning.

h)Shared understanding of assessment. Shared understanding of assessment was typically a concern of school leadership members who realised the need for a shared vision, common practice, and emphasis placed on using assessment information to inform ongoing teaching and learning.

Three trends stand out through these eight common themes: thinking about the effects of assessment (on learning and workload); a focus on more deliberate use of assessment to enhance student learning; and a desire to share the assessment process with others, particularly the learner. Less-common themes, such as those that arose in only one seminar location, related to thinking about affirmation of current practice, expanding the role of whānau in assessment, and how to incorporate key competencies or graduate profiles in school-wide assessments.

However, it is one thing to think about assessment, another to change practice. To that end, we asked participants about their intended professional practice.

2.Transforming reflections into professional practice

Eight themes emerged in relation to attendee’s intended changes in practice. Themes a to e, below, emerged from the three seminar centres, and themes f to h arose from two seminar centres.

a)Review our current practices. Uppermost in the minds of many respondents was the intention to review either their own classroom practice in assessment or that of their team or school. The intention was to question why and how they assessed, retain only the necessary assessment activities, and consider how to make assessments more relevant and meaningful for teachers and students.

b)Widen scope of assessment for learning. Weaving in key competencies or capabilities was the intention of some respondents. Others were prioritising student and teacher wellbeing or different techniques to foster assessment for learning, such as spider-webs, personalised, or group-based assessments. A few respondents wrote about the need to include parents or whānau in discussions about assessment.

c)Focus more on assessment for learning than on assessment for credits. Teachers of secondary school students reported dissatisfaction with the rigidity of NCEA standards assessment and a focus on credit mining or even credit “gaming”. Instead, they wanted to use a greater variety of assessments and to encourage junior students in self- and peer assessments to focus more on the learning process. A few respondents intended to develop more innovative and appropriate means of assessing 21st-century skills.

d)Converse with colleagues about assessment. Discussions about assessment with colleagues had the purpose of deepening knowledge about the technicalities and possibilities of assessments, as well as extending their contacts and networks with other schools and education stakeholders. Representative comments included: “Keep the conversations going with a number of schools in the room that we are working with—why, how, what will it look like, how are students co-creating with us? How are we celebrating our journey with colleagues, parents, whānau, and Kāhui Ako?”

e)Grow teacher knowledge about assessment. Clarifying the purpose of assessment in relation to learning, teaching, and curriculum was deemed important, along with development of skills in the formative use of assessment, particularly the provision of informative feedback to assist students with “next steps in their learning”.

f)Involve students more fully in the assessment process. There was an intention to develop assessment-capable students and involve them more regularly in creating relevant assessment tasks and formative use of assessment in their learning, e.g., “Keep getting more student voice”, “Co-construct success criteria with class and engage them in passion projects”.

g)Consult with stakeholders. Respondents intended to seek out the views of students, parents/whānau, and boards of trustees about the purpose of assessment, what they valued and needed, and to develop shared understandings. The need for shared understandings and relational trust was a particular concern of people involved in Kāhui Ako.

h)Develop ways of using technology to enhance assessment. A

few respondents were prioritising the creation of parent portals for the communication of assessment results and development of more efficient digital platforms for accessing and manipulating assessment information.

Thus, four of the themes related to people—seeking their input, discussing assessment purposes and possibilities with them, and growing assessment capability of teachers and students. Another notable point was the streamlining of assessments (through reviewing current practices and creating greater efficiencies with the affordances of digital technology) in order to more closely align assessment and learning. Themes specific to one of the three centres included development of graduate profiles and more meaningful collaboration across Kāhui Ako.

The final question related to the role that NZAI might play in assisting with the implementation of these practice plans.

3.Role of NZAI in building assessment capability

Five themes arose across the data from respondents:

a)Offer more workshops and seminars. A high proportion of respondents highly valued the opportunity for building their knowledge about assessment, stimulating thinking about or affirming their practice, and extending their professional networks. They particularly appreciated hearing about the latest research and innovative practice from other teachers in schools, and the opportunity to intermingle with researchers, professional-development providers, and personnel from various government and non-governmental agencies. School presenters valued the interest and affirmation they received from agency personnel, such as NZQA and ERO. For these reasons, particularly in deepening their knowledge of assessment and extending professional networks, they requested more workshops and seminars.

b)Create opportunities for professional conversations about assessment. The “rich discussion opportunities” with other people interested in assessment and learning were valued. Many respondents sought opportunities to provoke thinking and discuss new ideas with other educators, and other respondents sought clarification or extension of practical ideas and resources for classroom teaching. They requested more face-to-face and electronic means to stimulate ongoing professional conversations about future learning, teaching, and assessment.

c)Act as a purveyor of assessment research and practice resources/opportunities. Teachers were “thirsty” for greater “challenge from recent research”, identification of effective practice in schools they could potentially visit, updates on new assessment ideas, including research, thinkpieces, practical tips, and examples from which to adapt in their own professional circumstances. Suggestions for material to be accessible from the NZAI website, and specific materials to be made available, related to moderation, data aggregation, and building assessment capability.

d)Foster assessment-related relationships across stakeholders and education sectors. Respondents sought help with establishing links across other early childhood, primary secondary, and tertiary sectors. A few respondents were looking to create “trusting relationships” in assessment, usually in relation to home/school partnerships or relationships across Kāhui Ako. Others requested help with changing the focus of educational assessment “from standardisation and teaching to pass, towards learning and believing that everyone can develop as a learner and have a love of learning”. Most of all, they sought relationships that enabled all participants to seek feedback and to learn from one another.

e)Advocate for quality assessment. Comments in this theme included the following: “keep NZAI independent, apolitical, evidence-based with sound educational philosophy and practice”, “provide informed media comment on assessment”, “informed input into NZC [New Zealand Curriculum] discussion, extending beyond current MOE [Ministry of Education] thinking”. The overall tenor of comments in this theme related to the need for powerful change to enable a greater focus on assessment that informed meaningful learning, rather than assessment for the sake of it. To that end, respondents were keen that NZAI contribute to current reviews on education, represent members’ voices in the formation of new educational policies related to assessment, and ensure the use of assessment data to benefit learners.

Additional comments from individuals included the need for NZAI to expand its capacity to convey bicultural and multicultural perspectives on assessments. A few attendees sought assistance on the aggregation and analysis of data across schools and particularly across Kāhui Ako, and others were seeking exemplars of contemporary future-focused assessments and assessment of “soft skills” or “21st-century capabilities”.

Synthesis of themes

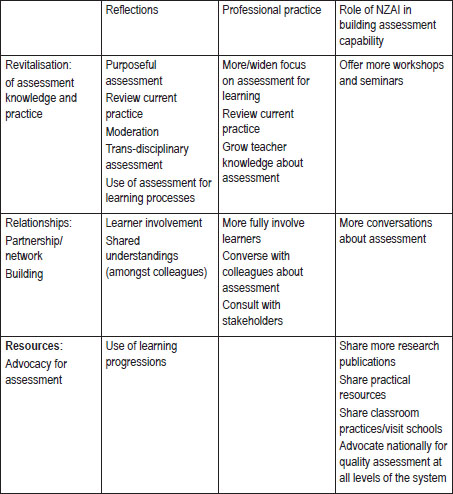

Further inductive analysis of the themes arising from the three questions (related to seminar respondents’ thinking about assessment, intended changes in their practice, and help that NZAI may be able to provide) revealed three higher level categories: revitalisation, relationships, and resources. Table 1 shows relationships between the themes and the more generic categories.

Table 1. Categories from Synthesised Themes for Building Assessment Capability

In effect, delegates were seeking assistance on three aspects: revitalisation of their assessment practices through rethinking and reviewing current assessment practices; relationships and network expansion; and additional resources such as research publications related to assessment, and practical ideas for implementation in the classroom or school. Growing assessment capability would appear to “go hand in glove” with relationship and network building, for respondents mentioned the value of conversations with a range of other educators (teachers as well as personnel from government agencies, and researchers) in their learning about assessment. Illustrative comments included, “Provide means for professionals to meet and share ideas, good practice in assessment”, and “set up forum/community networks where we can talk to each other”, “network with like-minded schools”, “share research articles/YouTube clips to upskill us and to bounce ideas off each other”.

Implications for assessment capability building

Building assessment capability is an ongoing adventure because assessment and learning are iterative processes responsive to learner needs and changing circumstances. Students differ year by year, as does the educational context with political, economic, social and cultural forces exerting varying influences (e.g., implementation and subsequent abandonment of National Standards).

Teachers have spoken—their enthusiastic presence at these assessment seminars during school holidays, and their responses on feedback sheets, demonstrates their desire to learn and become more assessment capable. Networks such as NZAI empower educators to share their assessment thinking, practice, and expertise—because individually we know and do a little, but collectively we can do and think a lot more. Educators indicated they seek to seize the opportunity to build their own, and their professional colleagues’ knowledge and practice in assessment because each person can grow so much more in assessment understanding. By engaging in respectfully challenging conversations with cross-sector colleagues, building relationship networks, and sharing assessment resources, assessment knowledge and practices are being revitalised.

References

Chamberlain, M. (2018, April). Keynote address: Where have we been? Where are we going? NZAI Rethinking assessment seminars. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Bmsj0TpT7DA&t=1616s

Hsieh, H., & Shannon, S. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Ings, W. (2018, April). The illusion of performance: How comparative testing distorts the way we understand learning. NZAI Rethinking assessment seminars. www.nzai.org.nz./events-seminars/resources-from-Auckland-nzai-seminar-18-april-2018/

Ministry of Education. (2011). Position paper on assessment. http://assessment.tki.org.nz/Media/Files/Ministry-of-Education-Position-Paper-Assessment-Schooling-Sector-2011

Poskitt, J., & Taylor, K. (2009). Final report: Evaluation of AtoL professional development. Auckland: Education Group Ltd.

Poskitt, J. (2014). Transforming professional learning and practice in assessment for learning. The Curriculum Journal, 25(4), 542–566. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585176.2014.981557

Poutasi, K. (2018, April). Qualify for the future world. NZAI Rethinking assessment seminars. www.nzai.org.nz./events-seminars/resources-from-Wellington-nzai-seminar-17-april-2018/

Smaill, E. (2018, April). Social moderation and the formation of assessment focused professional learning communities. NZAI Rethinking assessment seminars. https://www.nzai.org.nz/events-seminars/resources-from-christchurch-nzai-seminar-16-april-2018/

The author

Dr Jenny Poskitt is a senior lecturer in the Institute of Education at Massey University. Jenny’s research and teaching interests include assessment, professional learning, adolescent learning, and engagement.

Email: j.m.poskitt@massey.ac.nz