Sustaining assessment for learning by valuing partnerships and networks

Jenny Poskitt

https://doi.org/10.18296/am.0030

Abstract

Assessment for learning (AfL) improves student learning and achievement outcomes but, despite its positive effects, sustained implementation has been problematic. An examination of the policy environment, implementation factors that relate particularly to professional learning, and a New Zealand model of AfL, reveal gaps of interdependence at multiple levels. To bridge these gaps and the divide between policy intent and policy use, this article argues that dynamic learning partnerships are necessary to connect and mutually inform policy makers, influencers, and enactors. When all players understand why a policy such as AfL is needed, what it means, how to enact it, and are empowered to contribute, the policy becomes a lived reality. A co-ordinating alliance, like an assessment network, that deliberately connects and fosters relationships across and beyond education may be a means of forging valuable partnerships and networks to sustain assessment for learning.

Introduction

Assessment for learning (AfL) approaches are claimed to have improved student learning and achievement (e.g., Black & Wiliam, 1998). Extensive research has been conducted to verify these claims, including comparative studies with high student achievement effect sizes to indicate the impact of AfL strategies (Laveault & Allal, 2016a; Wiliam, 2010). Although there have been considerable successes in some classrooms and schools in numerous countries (Wylie & Lyon, 2015), attempts at more widespread implementation of AfL have been thwarted. Influential factors are thought to be variable understandings of AfL (Laveault & Allal, 2016a) and assessment literacies (Willis, Adie, & Klenowski, 2013), the policy making environment, insufficient professional development, and the process of implementation itself (Laveault & Allal, 2016b). Another pivotal concern has been the policy maker and policy user divide. “Policy-makers seek to convey precise meanings of educational policies, [yet] parents, school leaders and teachers may experience and construe the policies in other ways” (Ratnam & Tan, 2015, p. 63), resulting in differing understandings about the purpose and value of any given policy. Given these multifaceted factors and the distance between policy makers and policy users, it is not surprising that AfL policies often “fall over” at the school level.

Carless (2005) proposed an exploratory framework of three levels affecting AfL implementation in schools. Level 1 related to the personal domain (teacher knowledge and beliefs), level 2 to the micro level (local school influences), and level 3 to macro-level forces external to the school, such as government reforms. Carless (2005) argued teachers need sufficient depth of AfL understanding and aligned values to implement it. Required also is a school context conducive to professional change and an external environment of supportive academics and teacher educators. Additional influential factors include government policy and the impact of high-stakes testing.

This article takes the Carless framework further by proposing mechanisms for active partnerships across and between the levels. Active learning partnerships are necessary to connect and inform the three levels. The argument is that strengthening links between policy enactors (level 1—school), policy influencers (level 2—researchers, education stakeholders like professional development providers, unions), and policy makers (level 3) bridges the gap between policy formation and policy implementation. These connections are dynamic and require ongoing attention if AfL is to be centre stage and sustained.

The article is structured in three sections. Firstly, a brief review of the literature examines how educational policy is formed and the conditions that affect its implementation—AfL in particular. Since teachers operate at the critical level in which policy is, or is not, implemented, some understanding of how and why teachers change and principles of effective professional learning are relevant. From a synthesis of important elements of professional learning, the author posits that attention to the combination of professional learning factors may create conditions for improved implementation. Secondly, a national example is described of “across level” and “inter-level” partnerships in AfL. Thirdly, the article builds on the practical example to argue potential value in strengthening partnership processes and connections for aligning policy intent and sustained policy use.

Review of literature

Policy environment

Educational policy formulation is subject to international pressures, especially in a neoliberal environment, where education is associated with economic advancement (Laveault & Allal, 2016b). Politicians compare their education system with other jurisdictions to ascertain possible reasons for achievement differences, such as in Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) results (Volante, 2016). Governments then tend to adopt educational policies from other countries in the hope the policies will lead to improved student outcomes and, ultimately, economic advantage.

Typically, national educational policies are adopted/formulated at government or Ministry of Education level (e.g., Spencer & Hayward, 2016) with minimal or inadequate engagement by schools—the end users. This common practice of separating the policy makers from the policy users means the policy users have little, if any, understanding of why a policy has been made. Yet it is only when policy users interact with policy by negotiating understandings and practices (Adie, 2014) that implementation can occur. Ozga and Jones (2006) support this view by arguing that educational policies need to be adapted to local contexts if their impact is to go beyond superficial adoption. Indeed Poskitt (2016) argues that effective implementation requires a process of adaptation of the policy by the user (minor adjustments to suit their context) as well as adaptation to the policy (learning new skills or ways of thinking). In circumstances of open communication and collaboration, such an adaptive process can be mutually informative and beneficial. Under these conditions, not only is the policy negotiated and adjusted to be more appealing to practitioners, they feel valued by having opportunities to participate in policy processes. Consequently, practitioners have a better understanding of, and ownership towards, the resulting policy and engage more meaningfully in policy implementation (Poskitt, 2016). In ideal circumstances, this participatory process reduces the policy and practice divide. The reality is that most policy is a product of competing political, economic, cultural, and educational power struggles in compressed timeframes (Waldow, 2012). Current implementation tends, therefore, to compromise outcomes of these contestations.

Process of policy implementation

AfL implementation has been particularly troublesome. As Black (2015, p. 163) states, “given the wide range and differing approaches to developing formative assessment practices, it is hardly surprising that many difficulties have arisen”. Black (2015) argues many jurisdictions have encountered tensions between formative teaching approaches and accountability demands of standardised testing. Such tensions have altered understandings and practices of formative assessment, and made the process of change more complex. Moreover, insufficient time and resources have been invested in teacher professional learning in assessment (Black, 2015), and resulting in therefore incomplete teacher instruction and engagement with students’ in-classroom uses of AfL. Yet, fundamentally, AfL is “learning to learn” and “self-regulation” (Black, McCormick, James, & Pedder, 2006), for both the teacher and the learner. As such, considerable investment is required to foster change in teacher knowledge, understanding, and pedagogical practice.

Teacher change and professional development

But teacher change is not easy. Firstly, teachers need to perceive that change is required. When they are removed from the policy making process, teachers are deprived of realising the foremost reasons for AfL. Yet, critical to the change process are understandings related to why change, what to change, andhow to change.

The “why” needs to tap into teachers’ passion for learning and learners; so that teachers are motivated to engage in the change process (Säfström, 2014). New learning requires relinquishing familiar and trusted ways, to take on the unfamiliar and untried pedagogical practices. Letting go challenges teachers’ professional identity—the values, beliefs, and knowledge of the teacher (Buchanan, 2015; Mockler, 2011). When the new concept or practice aligns with basic beliefs about the learning process and the role of the teacher (professional identity), change is easier to adopt. When it differs, such as realising that assessment information is not merely to be recorded, but to be reflected on, to alter the learning and teaching sequence, then the process of change is more difficult—requiring considerable time and support. Emotions of anxiety, insecurity, and stress can be triggered, and need to be allayed through professional support and perceived benefits for student learning and achievement (Buchanan, 2015). These emotional and identity facets are frequently overlooked in the implementation of new policies.

The “what” of change necessitates growing teachers’ relevant knowledge. Sometimes dissonance (Timperley, Wilson, Barrar, & Fung, 2007) or disruption in current views are needed (such as student achievement data compared against age expectations or data from other similar students) to stimulate teachers’ thirst for new knowledge. DeLuca, Luu, Sun, and Klinger (2012) indicate that it is important to deepen teacher knowledge of curriculum content knowledge, pedagogical knowledge, and conceptions of assessment. Along with conceptions of assessment (purposes, functions, and processes), Luke and McArdle (2009, p. 243) deem four other categories of knowledge as essential for effective understanding:

•content knowledge (of specific disciplines and competing paradigms)

•pedagogical content knowledge (of field-specific and general pedagogies, assessment strategies, and techniques)

•curriculum knowledge (syllabus goals and standards)

•knowledge of students and community (knowledge of student background—cultural, cognitive, diverse community contexts).

All of these categories of knowledge are required for the effective application of AfL, yet few AfL professional learning programmes focus on all of these components in sufficient depth. The reader will perceive in the argument thus far, inadequate attention in implementation processes to the purpose (the “why”) for AfL policies, and content (the “what”) of AfL for teachers. There is one more element of change to consider—process (the “how”).

Translating teacher knowledge into classroom practice, the “how” of change could benefit from the application of at least eight principles of professional learning: understanding teachers as adult learners; the value of collaboration and positive relationships; opportunities for professional dialogue and reflection; professional readings, or input of external experts; mentors; sufficient time to trial and implement changes; leadership; and feedback. Each of these principles is now considered. Firstly, recognition that teachers are adult learners. Adult learners value relevant learning that relates to job-embedded improvement (centred on improving student and teacher learning and assessment), provides “hands-on” experiences, and acknowledges their prior life experiences (Finn, 2011; Gravani, 2012). Furthermore, effective learning for many adults is flexible, responsive to interests, and has a variety of individual and collaborative learning situations. These principles are contrary to most AfL professional learning programmes that are preplanned and delivered in a consistent fashion to multiple schools (Laveault & Allal, 2016b). In contrast, greater flexibility and responsiveness to differing preferences of teachers may foster more personally relevant, new learning. Indeed, Timperley et al. (2007) argue that giving teachers discretion, so long as their efforts are within a broadly agreed framework and direction, and that their change efforts are checked against the impact on students, results in more meaningful and sustained teacher change.

Opportunities for professional dialogue enable teachers to share emotions (Saunders, 2013) and practical pedagogical strategies; deepen, challenge, and co-construct knowledge; and build networks and support. Professional dialogue, when conducted respectfully, can lead to positive relationships and emotions, which are important in successful pedagogical practice (Hardy, 2016), and are key factors in classroom climates, for developing a sense of belonging and learner identity, and for teachers’ professional identity. Importantly, positive relationships cultivate mutual feelings of trust. Trust is essential for divulging uncertainties or confusions and therefore openness for new learning (Crooks, 2011). Fundamentally, teaching is relational, fostered through opportunities to collaborate with other professionals. Collaborative opportunities are important elements of professional learning because they enable teachers to learn informally from one another, by clarifying ideas, observing, and participating in new teaching experiences with support alongside other teachers. Observing and discussing other colleagues’ teaching practice often inspires new adaptations of one’s own practice. However, collaborative opportunities need to be purposeful and beneficial for teachers otherwise teachers resent the time involved. Collaboration is dependent not only on teacher willingness to be involved, but also on effective relationship skills, particularly skills in active listening and displaying interpersonal respect while disagreeing with professional perspectives. These latter communication skills are vital for honest exchange of ideas (Adams & Vescio, 2015), although paucity of interpersonal communication skills can restrict or damage professional conversations. Yet limited attention is given to communication skills in most AfL professional learning programmes.

A related skill is individual and collective reflection. Personal and interpersonal reflection helps teachers elicit current knowledge, and adjust and adapt that knowledge to “fit with” current circumstances (Grimmett & MacKinnon, 1992; Schon, 1983). Renewed awareness of existing knowledge helps to situate new knowledge and skills that may come from collegial interactions, professional readings, or the input of external experts (Timperley et al., 2007). This dynamic relationship between deepening content knowledge and professional reflection is foundational, though time consuming, for teachers inquiring into their practice (Clayton & Kilbane, 2016). But inward-looking reflections and practices only go so far; new perspectives may require assistance from outside experts or mentors.

Mentors perceive potential and inspire capabilities for learning and teaching (Achinstein & Davis, 2014) of which the individual teacher may be unaware or lacking in confidence. Mentors provide teachers with emotional and psychosocial support; assist their mentees to construct personal and practical pedagogical knowledge; help foster reflection; and build strategies for ongoing growth to develop competent and confident professionals. Mentoring requires awareness of the twofold nature of the task: what constitutes effective teaching and assessment; and how to transform a novice into an expert teacher (van Ginkel, Oolbekkink, Meijer, & Verloop, 2016). Such mentoring knowledge and skills need fostering—a facet rarely deliberately cultivated in assessment-related professional learning.

Sufficient time is necessary for teachers to apply new knowledge to practice, and to allow for sustained professional learning. Although WeiBenrieder et al. (2015) indicate at least 8 hours per month is required for meaningful professional learning to impact teacher practice and student learning, Timperley et al. (2007) argue that the way the time is used is more critical than the amount. “Teachers need to have time and opportunity to engage with key ideas and integrate those ideas into a coherent theory of practice” (Timperley et al., 2007, p. 225). The reader may sense how the principles of professional learning discussed thus far are not isolated, independent factors, but rather, interdependent factors. It is not just the provision of sufficient time that is important; it is the optimal use of professional learning time—for activities such as professional dialogue, deepening assessment knowledge, reflection on practice, mentoring, and collaborative practice (Timperley et al., 2007). To understand this interdependent nature of effective professional learning and to plan and execute it with associated resources requires vision and a committed leadership team. Active, strong leadership is necessary for stimulating and sustaining the vision of AfL, especially in political climates of summative testing demands (Black, 2015; Volante, 2016). Where leadership (at team, school, and national levels) has been lacking, AfL has languished.

Another important factor is monitoring progress (Timperley et al., 2007) at teacher and organisational levels because using the monitoring information allows adjustments and refinements to occur to pedagogical and organisational practice, such as the need for deeper pedagogical content knowledge. It is important, therefore, to collect evidence of student achievement and progress in relation to pedagogical and assessment strategies trialled, and thereby help teachers perceive the impact of their endeavours on students’ thinking. Regular feedback to guide teachers’ efforts in implementing AfL, particularly the involvement of students in discussing their learning, formulating goals, and pertinent criteria is necessary, yet rarely practised. In eight projects he reviewed, Black (2015) found no evidence of classroom dialogue to foster students’ understanding of assessment or capacity to learn. Often the reason given is limited time in the school day.

Some teachers could benefit from observing other colleagues or facilitators skilled in aspects such as generating interactive dialogue with students, or constructing quality feedback processes. Gadd (2014) has long maintained the importance of teacher modelling, followed by regular reflective debriefing sessions, action planning, and subsequent observation for implementing modified teaching practices. Related processes in the research literature include instructional rounds (e.g., DeLuca, Klinger, Pyper, & Woods, 2015) and inquiry learning (e.g., Hardy 2016; Timperley & Parr, 2007) which can improve teacher knowledge and practice. Instructional rounds involve identifying a pedagogical problem; collaboratively developing and implementing strategies; engaging in peer classroom observations; and professional conversations to de-brief and reflect (DeLuca et al., 2015). Inquiry learning is similar but identifies a worrisome aspect of student learning. Collectively, teachers identify knowledge and skills they wish to develop. They then trial the ideas, gather evidence of their impact, and reflect on ongoing modifications (Hardy, 2016). But limited analysis and content knowledge weaken inquiry learning (Clayton & Kilbane, 2016). Sustained professional learning appears to arise from dynamic interactions between various principles of professional learning (such as deepening knowledge and extending interpersonal skills) to address individualised and collective teacher needs.

In summary, it seems that effective policy implementation at school level necessitates attention to a combination of numerous professional learning principles in three broad categories: relationships; teacher knowledge and pedagogical practice; and encouraging conditions. Incorporation of principles that respect teachers at a personal level and build staff relationships include adult learning principles; building positive communication and relationships; and creating opportunities for dialogue and reflection. In terms of increasing teacher knowledge and pedagogical practice, periodic assistance from external experts and mentors, professional reading, stimulating new knowledge, and opportunities to apply new practices with support and feedback over sustained time are helpful. Encouraging conditions for collaborative learning include active leadership and appropriate monitoring of progress to support ongoing learning. In political climates of competing demands and expectations, scant attention to some of these fundamental components of professional learning means, unsurprisingly, implementation of AfL is incomplete.

External influences

Problems with policy implementation of AfL extend beyond the school. “Parents can form a source of pressure on teachers’ [assessment] practices as well as the curriculum, particularly in the elementary grades” (Ratnam & Tan, 2015, p. 64). In climates of high-stakes assessment, the ways in which parents/families interpret, translate, and value assessments influence the extent to which they engage with teacher feedback and judgements of their child’s achievements. Parents’ views about assessment are shaped by their own educational experiences as well as their knowledge and expectations of the workforce. What they value, or perceive is valued, in securing future employment for their children influences their interactions with school assessment information. Indeed, Ratnam and Tan (2015) found parents’ reactions to holistic assessment severely restrained the implementation of innovations in the Singaporean education system.

Implicit here is the need to inform and involve parents in AfL policy implementation, but more so, to involve wider business and employers groups. Carless (2005) referred to this as the macro-level forces external to the school. However, there is also a mindset issue. If the public continue to value only summative-assessment information, then AfL implementation is stymied. Most future-focused employers and businesses value employees who continually seek improvement, innovation, and ongoing learning. AfL is at the heart of these desirable employment attributes. One means of raising awareness and garnering support could be through learning partnerships.

Learning partnerships

Fostering of learning partnerships may be a potential pathway for bridging the policy and practice divide with AfL. Partnerships can bring mutual benefits including shared understandings and increased access to resources. Willems and Gonzalez-DeHass (2012) described school–community partnerships as

meaningful relationships with community members, organisations and businesses that are committed to working cooperatively with a shared responsibility to advance the development of students’ intellectual, social and emotional well-being. (Gross, Haines, Hill, Francis, Blue-Banning & Turnbull, 2015, p. 10)

Among other measures of school engagement, Guevara (2014) maintains schools with strong community partnerships have higher percentages of students performing at grade level and achieving higher test scores. Trusting community–school partnerships not only contribute to positive student outcomes but also develop common goals (across community members, agencies, organisations, business, and industry) to work collaboratively—resulting in “direct participation by community representatives in school leadership and enhanced community resources” (Gross et al., 2015, p. 11). Both schools and communities benefit from resource sharing in partnerships, particularly when principles of reciprocity (mutual benefit), diversity, and variety (of purposes, personnel, and means) underpin the partnerships.

Schools can reach out to their wider communities through “boundary spanners”—“leaders who bring people together across traditional boundaries to work towards a common goal” (Adams, 2014, p. 113). These boundary spanners can convey influence, negotiate power and balance, but also promote mutual partnerships by encouraging understanding of each party’s “perceptions, expectations and ideas” (Adams, 2014, p. 114). In being community champions, these boundary spanners often generate trust and empathy through eliciting the perspectives of others, listening, and creating shared action plans that represent the views of all parties. Moreover, boundary spanner leaders develop a vision that unites and benefits all involved. “Strong school leadership, inviting school culture, educator commitment to student success, [and] ability to collaborate and communicate with community partners” (Gross et al., p. 9) optimise school–community partnerships. In essence, respectful alliances value authentic, trusting relationship building, dialogue, and power sharing.

However, Brackmann (2015) argues that, in a neoliberal environment, partnerships often exhibit power imbalances where one partner has more wealth and resources than the other partner or wields more power and influence. Different types of partnerships can be formed—from the structured with formal solicitation of membership, matching of experts, and contract requirements; to the semistructured, characterised by fluid processes; through to the unstructured which is formed from word-of-mouth reputations and informal recruitment. Unstructured processes favour organisations with more social capital and members with networks of personal connections. Brackmann (2015) argues, regardless of the degree of structure, the ideal partnership is characterised by a shared voice and participation. Indeed, “those involved in transformative partnerships highlighted desires to change society or communities through their programmes” (Brackmann, 2015, p. 130). For some partnerships, deep change is sought; for other more enduring partnerships, exchange-based relationships (mutual benefits and reciprocity) are favoured.

Exchange-based relationships are arguably the most suited to school relationships with their parent, local, and business communities since most schools are limited by resources but not by passion for learning and learners. Such moral purpose—of desiring the best for students, their current and future learning and wellbeing—is the underlying belief that has power to unite schools with their local, medial, and overarching communities. Rather than arguing over minutiae, educators and the public who collaborate mutually inform and assist one another for the benefit of students and society.

How might an exchange-based relationship unite the education sector and stakeholders?

Assess to Learn (AtoL): National assessment professional development programme

The next section of the article examines a sustained (8-year) programme of assessment for learning that drew on, and built, a range of professional networks. The nationwide example-in-practice, illustrates what is possible and what can be learnt from interactions across policy makers, policy influencers, and policy enactors.

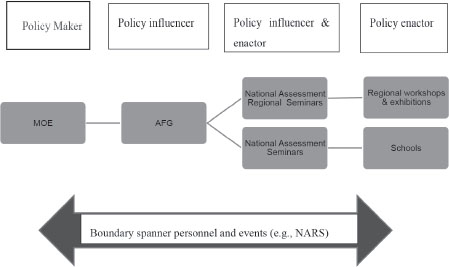

The Assess to Learn (AtoL) professional development programme in New Zealand is an example of an education sector partnership strategically connecting the policy maker (Ministry of Education), though the policy influencer (medial level, including unions, researchers, professional development providers), to the policy enactor (local school level) to implement AfL. Refer to Figure 1.

Figure 1. Nationally Co-ordinated Assess to Learn Programme: Policy Maker to Policy Enactor

The Ministry of Education co-ordinated AtoL nationally. Eight providers successfully tendered to deliver AtoL over an 8-year period between the years 2002–10. Each professional development provider comprised a national director and a team of facilitators who worked in AtoL schools in their respective geographic regions. Schools were invited to participate in AtoL, based on either application or “shoulder tapping” from various educational agencies (e.g., lower performing schools, or particular schools identified by the Education Review Office with an assessment need). Although a few schools participated in AtoL for only 1 year, most schools participated for 2 years. Occasionally, schools continued for 3 consecutive years in AtoL. In most regions, AtoL schools predominantly worked individually with their allocated facilitator. In other regions, the school senior management team was involved in cluster workshops for the first year. If they continued with AtoL in the subsequent year(s), they worked intensively in the school with an external facilitator (Poskitt, 2014).

Developing relationships and partnering

AtoL relationships were fostered at four levels: national; medial; local; and intersecting levels. For the purposes of this article, the national level included the policy maker, the Ministry of Education, and policy influencers: AtoL directors and research/evaluation team. The medial level included policy influencers: university researchers; Initial Teacher Education; professional development facilitators; teacher union representatives; and independent agencies, such as the New Zealand Council for Educational Research and the Education Review Office. The intersecting level across the national, medial, and local levels included the research/evaluation team. Descriptions of each of these relationship levels follow.

1.National level : Ministry of Education and AtoL directors

Throughout the AtoL programme, bimonthly meetings of the provider directors, the research/evaluation team, and the Ministry of Education occurred. These “Assessment Focus Group” (AFG) meetings served several purposes. Namely, to:

•update the team on Ministry of Education initiatives

•co-construct the national research/evaluation tools, report data, or plan subsequent actions based on research outcomes

•report regional developments and periodically engage in shared problem solving among providers

•provide advice or input to the Ministry of Education on emerging strategies

•plan upcoming events.

The AFG meetings served other informal purposes of emotional support (realising other providers experienced similar issues), inter-regional connections, and shared problem solving (new knowledge and strategies). For example, during the regional updates section of the agenda, directors were informed about emerging trends and issues in each of their regions. Such updates led to realisations of regional variations and commonalities (e.g., two regions covered proportionally larger geographical areas and tended to work with smaller, rural schools). This reality created issues of additional travelling time/costs for these facilitators and limited face-to-face sharing opportunities for their school clusters, but opportunities for creative problem solving (e.g., electronic networking). Most providers encountered challenges effecting change in larger secondary schools, and with “reluctant to change” schools, and shared strategies they were trialling. In effect, the bimonthly AFG meetings created conditions for friendships and reciprocal professional help-seeking connections and networks to develop among the directors (and vicariously, their facilitation teams).

2.Medial level: Professional development facilitators, unions, pre-service educators, and researchers

At the medial level, two New Zealand-wide AfL events occurred: National AtoL Seminars and National Assessment Regional Seminars. These events involved policy enablers.

Firstly, the National AtoL Seminars occurred twice-yearly with the primary purpose to update and upskill assessment facilitators. Typically, the 2-day seminars were occasions for the Ministry of Education to update facilitators on their latest thinking, as well as undertake planning and tool development in assessment (to ensure consistent messages in schools). Various Ministry personnel attended and delivered workshops on related topics such as literacy progressions and Numeracy Project developments. Representatives from national assessment programmes were regularly invited to the workshops. For example, the New Zealand Council for Educational Research (NZCER) was invited to “show and tell” the latest tool developments (e.g., PAT Comprehension test, Assessment Resource Banks); the National Evaluation and Monitoring Project (NEMP) representatives provided updates on either tools (e.g., Self-assessment instrument) or data analysis from the previous year’s monitoring. Ministry Curriculum and Leadership personnel attended, and Te Kete Ipurangi (TKI) (Ministry of Education electronic platform and web-based resources) representatives demonstrated the latest resources. Time allocated for national AtoL evaluation planning or trend analysis, as well as round table discussions, enabled facilitators to share innovative practice and problem solve mutual concerns.

In the latter years of AtoL, invitations to one or two schools to present innovative practices at the National Seminar created opportunities for inter-level (policy influencer and policy enactor) information sharing. Invited schools shared their successful practice with facilitators from other regions. These sessions extended connections and learning partnerships beyond the invited schools and facilitators of schools in other regions, to schools around the country as facilitators shared the ideas and network connections with schools in their regions. Thereby National AtoL Seminars created opportunities for professional friendships, network partnerships (intra- and inter-regional), and reciprocal sharing of ideas and resources across the policy influencer (facilitator) and into the policy enactor (school) level.

The second event, National Assessment Regional Seminars (NARS), became a boundary-spanning opportunity. Although NARS were essentially regional conferences for teachers from both AtoL and non-AtoL schools, NARS created opportunities for teachers to initiate and extend professional relationships across the educator sector, with stakeholders, and with personnel from the policy influencer and policy maker levels. Accordingly, in attendance were: AtoL teachers; prospective AtoL school members; representatives from the primary and secondary teacher school unions; Education Review Office; Ministry of Education regional and national office personnel; academics/researchers; professional development advisers/facilitators; Initial Teacher Education personnel; NZCER; and occasionally school product promoters. The structure of NARS comprised a mix of keynote addresses by national and international assessment experts (e.g., Crooks, Flockton, Sadler, Stobart) and the current Minister of Education, researcher presentations, and teacher workshops (the latter typically presented by “shoulder-tapped” AtoL school personnel). Ensuing discussions deepened professional knowledge about conceptions of assessment, developed awareness of innovative practice, inspired attendees in aspects of assessment for learning, provided strategies and resources for use in the classroom, created professional camaraderie and networking connections, and continued to prioritise assessment in the minds and actions of teachers. Thus, NARS created considerable opportunities for professional relationship and partnership building across schools, with people in the policy maker and policy influencer levels.

3.Local level: Exhibitions, mentor, and buddy schools

At the school level, regional variations occurred, but each AtoL provider established at least a yearly means of AtoL schools coming together. In one region, an end-of-year AtoL Exhibition “showcased” and celebrated school achievements. Each school shared highlights of its AtoL journey, informing and inspiring other schools. An invited speaker deepened attendees’ knowledge and conceptions of assessment, and the presence of Ministry of Education personnel further endorsed the value of AfL. These occasions fostered new learning partnerships between teachers and across schools. For example, “buddy” and “mentor partners” were established in two regions, where experienced AtoL schools paired with one or more new schools to support them in the AfL journey.

4.Intersecting levels: Research/evaluation team

Two researchers evaluated the AtoL programme over the 8 years. Annual beginning- and end-of-year data were collected by way of principal and teacher questionnaires, facilitator interviews, classroom observations, and student achievement data. Emerging trends were reported to AFG meetings and the AtoL facilitator national seminars to inform ongoing practice, and to serve the Ministry’s accountability requirements. Researchers interacted at all levels of the programme—from the national Ministry level (policy maker), through the medial (policy influencer) and local school (policy enactor) levels. The research served to increase understanding of the contribution of each level towards AfL, and mirrored assessment for learning by way of providing feedback to facilitators and the Ministry.

Figure 2. Relationship and Partnership Network

Discussion

Evident in the AtoL programme are incidents of mutual sharing of knowledge and expertise, collaborative partnerships, and networking within levels and across levels. In effect, the AtoL directors, facilitators, and researchers acted as policy influencers, or “boundary spanners”, between the Ministry of Education (policy makers) and the policy enactors (schools). Furthermore, they interacted at NARS with union representatives, researchers, other educational agencies, and networks of schools. These interactions led to increased awareness of, and respect for, collegial roles and perspectives. An emerging sense of common purpose and solidarity arose related to assessment for learning. There was a realisation that collaborative networks across the education sector were mutually beneficial for all involved. More could be accomplished collectively, through AfL, than individually. These characteristics align with Sachs’ (2003) notion of activist or transformational teacher professionalism. Sachs argues that, by building and promoting collaborative development, professional dialogue generates new insights and improvements:

Spaces are created for new kinds of conversations to emerge. They provide opportunities for all groups to be engaged in public critical dialogues and debates about the nature of practice, how it can be communicated to others and how it can be continually improved. All parties move from peripheral involvement in individual and collective projects to full participation. Dialogue is initiated about education in all its contexts and dimensions, and about how people can learn from the experiences and collective wisdom of each other. (Sachs, 2003, p. 143)

Full participation and interactive dialogue occurred within and across the education sector in the AtoL programme—but the missing component was attention to macro-level external forces (Carless, 2005); an outward-looking focus and activist orientation. Active participation of the parent, business, and political communities was omitted—a fundamental component in Hargreaves’ (2000) notion of the postmodern professional. Limited participation by the wider education sector and relevant parent, business communities and alternative pressure on politicians, may have contributed to the policy environment change around 2011. Pressures of accountability and summative assessment came in the guise of international testing results like PISA, the New Zealand senior secondary school qualification National Certificates of Educational Achievement (NCEA), and National Standards (NS). Despite opportunities for AfL being embedded within NCEA and NS at the individual student and system level, misunderstandings and distrust arose from limited opportunities for schools to be actively involved in the associated policy making (Poskitt, 2016). Unions activated resistance on issues of time and workload. Professional development consultants resorted to “training” related to tool use because there were insufficient resources provided for in-depth professional learning. Confusion arose for teachers as to what had happened to “AfL”. With reports of increased workloads, more visible accountability, and increased uncertainty, attention to AfL lessened in New Zealand.

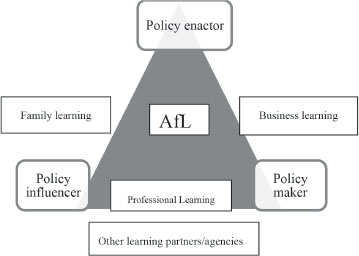

Towards a new assessment for learning partnership model

A new way of thinking about AfL policy implementation is proposed. Figure 3 displays the policy enactor at the top in policy making processes and more directly linked to both the policy maker and policy influencers. Direct and closer links between the policy maker and the policy enactors could enhance the clarity of the policy meaning and purpose of policy, and engage teachers’ motivation and passion for learning and assessment. Also, stronger links to the policy influencers could help to optimise the “what and how” of professional learning for schools, with greater flexibility to adjust professional learning to suit particular needs of teachers and schools.

Figure 3. A New Assessment for Learning Policy Partnership Model

Note the central place of AfL in Figure 3, and embedded professional learning to establish and sustain AfL in schools. Learning partnerships with families and business communities and other agencies could help develop a common understanding, and valuing, of AfL. When external forces align with education sector interests, there may be a greater likelihood for sustainable policy.

The notion of learning partnerships has several key connecting elements of the triangle.

•Vertices: Intra-education. The vertices of the triangle connect the policy maker, policy influencers, and policy enactor to form a cohesive education sector.

•Edges: Inter-agencies. The edges (lines) of the triangle symbolise learning partnerships fostered between each of the policy maker, policy influencers, and policy enactors with parents, business, and other partners or agencies.

•Inner triangle: AfL implementation links the passions and interests of all connected with education. The need for, and support of, AfL in the learning of students, the professional learning/development of teachers, and adults as life-long learners (parent, business, and community connections).

Educators across the policy making, influencing, and enacting levels have an opportunity to engage in authentic discussions with the wider public about learning and assessment, share understandings of what the business and public sector seek from education, and what education can realistically deliver. Furthermore, they could develop solidarity on the value of life-long learning, at the heart of which is self-regulated learning, including assessment for learning. This situation creates opportunities for “ground up” partnerships across the local community, to include a range of agencies, private- and public-sector organisations, and businesses. Direct participation could lead to mutual benefit of shared understandings and resources (Guevara, 2014), especially when the partnerships are based on principles of reciprocity (mutual benefit), diversity, and variety (of purposes, personnel, and means).

Time is of the essence for the three levels (policy maker, influencer, and enactor) to collectively build awareness and skills of the education sector to seize this AfL opportunity. Networking, advocacy, and knowledge mobilisation seem to be keys to educational reform, “placing educational practice [assessment for learning] at the centre, providing the kind of social and professional nourishment that leads members [and the public] to invest time, effort and commitment far beyond” usual activity (Sachs, 2003, p. 151).

Perhaps national policy making might not be primarily the jurisdiction of government officials. Nor may it be reasonable to expect schools to carry sole responsibility for the implementation of policies like AfL. Rather, maybe the making and the enactment of policy is the responsibility and privilege of all, “because people are more committed to solutions they have had a hand in developing” (Rubinstein, 2014, p. 22). Furthermore, solutions or policies in which various player voices have contributed can be more productive and higher performing (Rubinstein, 2014).

As educators and members of a democratic society, educators have a right and a mutual obligation to be educational policy influencers and enactors—communicating, contributing, and collaborating in learning partnerships to influence and enhance educational policy making and policy enacting. Valuing partnerships in learning and assessment gives greater likelihood of sustainable and reciprocal student, teacher, and community learning,

If there is merit in the notion that policy making and policy enacting may benefit from combined participation of policy makers, policy influencers, and policy enactors, specifically in the area of sector-wide assessment to serve learning, then a facilitative or co-ordinating “body” or “network” may be desirable. In practical terms, a co-ordinating assessment body—an assessment network of AfL representatives across the policy maker, policy influencer, and policy enactor roles—may help operationalise this aspiration. A networking “body” could connect and unify representatives to foster and sustain the relevance of AfL from preschool, primary, and secondary school, tertiary, and into workplace environments. Gross et al. (2015) argue that strong network partnerships are dependent on champions who serve three functions: garner and facilitate commitment to a common cause; actively lead and nurture the network; and create opportunities for network partners to communicate and collaborate. An assessment network could serve as a championing organisation and ultimately foster opportunities for students, the wider community, and business representatives also to be involved because “real change requires both professional and political action to ensure that all communities, including parents and employers, as well as teachers, policymakers and researchers, are part of the process” (Hayward & Spencer, 2010, p. 174). Network partnerships do take time and work, but “once a culture and system of collaboration is institutionalised, great results do emerge” (Rubinstein, 2014, p. 28).

References

Achinstein, B., & Davis, E. (2014). The subject of mentoring: Towards a knowledge and practice base for content-focused mentoring of new teachers. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnerships in Learning, 22(2), 104–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/13611267.2014.902560

Adams, A., & Vescio, V. (2015). Tailored to fit: Structure professional learning communities to meet individual needs. Journal of Staff Development, 36(2), 26–28.

Adams, K. (2014). The exploration of community boundary spanners in university–community partnerships. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, 18(3), 113–118.

Adie, L. (2014). The development of shared understandings of assessment policy: Travelling between global and local contexts. Journal of Education Policy, 29(4), 532–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2013.853101

Black, P. (2015). Formative assessment: An optimistic but incomplete vision. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 22(1), 161–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2014.999643

Black, P., McCormick, R., James, M., & Pedder, D. (2006). Learning how to learn and assessment for learning: A theoretical inquiry. Research Papers in Education, 21, 119–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671520600615612

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 5(1), 7–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969595980050102

Brackmann, S. (2015). Community engagement in a neoliberal paradigm. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, 19(4), 115–146.

Buchanan, R. (2015). Teacher identity and agency in an era of accountability. Teacher and Teaching Theory and Practice, 21(6), 700–719. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1044329

Carless, D. (2005). Prospects for the implementation of assessment for learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 12(1), 39–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594042000333904

Clayton, C., & Kilbane, J. (2016). Learning in tandem: Professional development for teachers and students as inquirers. Professional Development, 42(3), 458–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2014.997397

Crooks, T. (2011). Assessment for learning in the accountability era: New Zealand. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 37, 71–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2011.03.002

DeLuca, C., Klinger, D., Pyper, J., & Woods, J. (2015). Instructional rounds as a professional learning model for systematic implementation of assessment for learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 22(1), 122–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2014.967168

DeLuca, C., Luu, K., Sun, Y., & Klinger, D. (2012). Assessment for learning in the classroom: Barriers to implementation and possibilities for teacher professional learning. Assessment Matters, 4, 5–29.

Finn, D. (2011). Principles of adult learning: An ESL context. Journal of Adult Education, 40(1), 34–39.

Gadd, M. (2014). What is critical in the effective teaching of writing? A study of the classroom practice of some year 5 to 8 teachers in the New Zealand context. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, The University of Auckland, Auckland.

Gravani, M. (2012). Adult learning principles in designing learning activities for teacher development. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 31(4), 419–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/02601370.2012.663804

Grimmett, P., & MacKinnon, A. (1992). Craft knowledge and the education of teachers. In G. Grant (Ed.), Review of Research in Education, 18, 385–456. https://doi.org/10.2307/1167304

Gross, J., Haines, S., Hill, C., Francis, G., Blue-Banning, M., & Turnbull, A. (2015). Strong school–community partnerships in inclusive schools are “part of the fabric of the school … we count on them”. School Community Journal, 25(2), 9–34.

Guevara, F. (2014). Vehicle of change: The PS 2013 campaign. VUE, 39, 16–25.

Hardy, I. (2016). In support of teachers’ learning: Specifying and contextualising teacher inquiry as professional practice. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 44(1), 4–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2014.987107

Hargreaves, A. (2000). Four ages of professionalism and professional learning. Teachers and Teaching: History and Practice, 6(2), 151–182. https://doi.org/10.1080/713698714

Hayward, L., & Spencer, E. (2010). The complexities of change: Formative assessment in Scotland. The Curriculum Journal, 21(2), 161–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585176.2010.480827

Laveault, D., & Allal, L. (Eds.). (2016a). Assessment for learning: Meeting the challenge of implementation. The Enabling Power of Assessment Series. Heidelberg, Switzerland: Springer.

Laveault, D., & Allal, L. (2016b). Implementing assessment for learning: Theoretical and practical issues. Chapter 1 in Part 1: Assessment policy enactment in education systems. In D. Laveault & L. Allal (Eds.), Assessment for learning: Meeting the challenge of implementation (pp. 1–20). The Enabling Power of Assessment Series. Heidelberg, Switzerland: Springer.

Luke, A., & McArdle, F. (2009). A model for research-based state professional development policy. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 37(3), 231–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598660903053611

Mockler, N. (2011). Beyond ‘what works’: Understanding teacher identity as a practical and political tools. Teachers and Teaching, 17(5), 517–528. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2011.602059

Ozga, J., & Jones, R. (2006). Travelling and embedded policy: The case of knowledge transfer. Journal of Educational Policy, 21, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930500391462

Poskitt, J. (2014). Transforming professional learning and practice in assessment for learning. The Curriculum Journal, 25(4), 542–566. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585176.2014.981557

Poskitt, J. (2016). Communication and collaboration: The heart of coherent policy and practice in New Zealand assessment. Chapter 6 in Part 1: Assessment policy enactment in education systems. In D. Laveault & L. Allal (Eds.), Assessment for Learning: Meeting the challenge of implementation (pp. 81–96). The Enabling Power of Assessment Series. Heidelberg, Switzerland: Springer.

Ratnam, C., & Tan, K. (2015). Large-scale implementation of formative assessment practices in an examination-oriented culture. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 22(1), 61–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2014.1001319

Rubinstein, S. (2014). Strengthening partnerships: How communication and collaboration contribute to school improvement. American Educator, 37(4), 22–28.

Sachs, J. (2003). The activist teaching profession. Professional Learning Series. Philadelphia: Open University Press.

Säfström, C. (2014). The passion of teaching at the border of order. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 42(4), 337–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2014.956045

Saunders, R. (2013). The role of teacher emotions in change: Experiences, patterns and implications for professional development. Journal of Educational Change, 14, 303–333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-012-9195-0

Schon, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner—How professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books.

Spencer, E., & Hayward, L. (2016). More than good intentions: Policy and assessment for learning in Scotland. Chapter 7 in Part 1: Assessment policy enactment in education systems. In D. Laveault & L. Allal (Eds.), Assessment for learning: Meeting the challenge of implementation (pp. 111–127). The Enabling Power of Assessment Series. Heidelberg, Switzerland: Springer.

Timperley, H., & Parr, J. (2007). Closing the achievement gap through evidence-based inquiry at multiple levels of the education system. Journal of Advanced Academics, 19, 90–115. https://doi.org/10.4219/jaa-2007-706

Timperley, H., Wilson, A., Barrar, H., & Fung, I. (2007). Teacher professional learning. Best evidence synthesis iteration [Bes], 292. Wellington: Ministry of Education. http://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/publications/series/2515.

van Ginkel, G., Oolbekkink, H., Meijer, P., & Verloop, N. (2016). Adapting mentoring to individual differences in novice teacher learning: The mentor’s viewpoint. Teachers and Teaching, 22(2), 198–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2015.1055438

Volante, L. (Ed.). (2016). The intersection of international achievement testing and educational policy. Global perspectives on large scale reform. New York: Routledge.

Waldow, F. (2012). Standardisation and legitimacy: Two central concepts in research on educational borrowing and lending. In G. Steiner-Khamsi & F. Waldow (Eds.), World yearbook of education 2012. Policy borrowing and lending in education (pp. 411–423). New York: Routledge.

Wiliam, D. (2010). An integrative summary of the research literature and implications for a new theory of formative assessment. In H. Andrade & G. J. Cizek (Eds.), Handbook of formative assessment (pp. 18–40), New York, NY: Routledge.

Willis, J., Adie, L., & Klenowski, V. (2013). Conceptualising teachers’ assessment literacies in an era of curriculum and assessment reform. Australian Educational Researcher, 40(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-013-0089-9

Wylie, E., & Lyon, C. (2015). The fidelity of formative assessment implementation: Issues of breadth and quality. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 22(1), 140–160. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2014.990416

The author

Dr Jenny Poskitt is a senior lecturer in the Institute of Education at Massey University. Jenny’s research and teaching interests include assessment, professional learning, adolescent learning, and engagement.

Email: j.m.poskitt@massey.ac.nz