Teaching literacy in a time of environmental crisis

Sasha Matthewman with John Morgan, Molly Mullen, Rawiri Hindle, and Michelle Johansson

Key points

•The research argues for a 3D literacy model which purposefully includes environmental as well as cultural perspectives.

•3D eco-literacy attends to dimensions of literacy and identity for all the learning areas in the curriculum.

•This article gives an overview of the collection of papers presented in this issue of set from the TLRI project Tuhia ki Te Ao—Write to the Natural World.

In Aotearoa New Zealand we need an informed educational response to the environmental crisis within and across all learning areas in the curriculum. One way of organising that response is through the concept of eco-literacy. This article explains the concept of eco-literacy developed within the TLRI project Tuhia ki Te Ao—Write to the Natural World, and introduces the collection of four articles from the project published in this issue of set. This introductory article outlines how the model of eco-literacy has been enacted within the learning areas of English, the Arts, and Social Sciences, and indicates how eco-literacy is connected to Māori and Pasifika cultural perspectives within the full articles.

In times like these

To have you listen at all, it’s necessary

to talk about trees

~ Adrienne Rich, “In Times like These”

In times like these we need to teach as if place and planet matter. New Zealand is fêted as a place of “pristine” natural beauty, but at the same time the pace of urban development and intensification of rural agriculture is threatening the waters and the soils. Bigger issues loom on a global scale with the threats of sea-level rise, flooding, and landslides associated with climate change (IPCC, 2014; Morton, 2017). At the same time children’s contact with nature is diminishing and the language to name and speak for nature is being eroded (see Louv, 2005; Macfarlane, 2015, and Matthewman, Rewi & Britton, this issue). Rather than responding with despairing pessimism or blithe optimism, the educational response needs to be positive, active, informed, and hopeful.

In our TLRI1 project team, Tuhia ki Te Ao—Write to the Natural World, we believe that it is ethically and intellectually important to explore the potential of literacy to “speak for” and represent the natural world within all the learning areas of the school curriculum. We already know that literacy is not just a technical fix and that it involves learning attitudes, values, and knowledge and culture (Ferdman, 1990). Literacy connects to identity, and this is well established in relation to children’s cultural and digital identities (see Gee, 2003). But what about children’s emergent environmental identities? How can learning literacy connect with this set of values, beliefs, attitudes, and knowledge? How does each learning area in the curriculum help students to relate to the environment?

This short article is an introduction to the thinking about literacy that underpins the project, while the articles in this Tuhia ki Te Ao—Write to the Natural World section grapple with more culturally located and subject-specific questions of eco-literacy in teaching and learning within three learning areas: English, the Arts, and Social Sciences.

There are a variety of synonyms for eco-literacy, such as environmental literacy, sustainability literacy, and ecological literacy. Eco-literacy in this sense refers to developing knowledge about the environment, nature, and ecology, including issues of sustainability (Orr, 2004). In our team we recognise the importance of ecological knowledge, but we define eco-literacy in relation to practices of literacy. We are interested in how learning areas use texts (spoken, visual, written, and performed) and subject-specific practices of meaning making to communicate ecological values (see Kalantzis & Cope, 2012, for a framework of different modes of making meaning). Literacy is already firmly established as being about culture (Ferdman, 1990; Hirsch, 1987), but we argue that a more holistic understanding of literacy is about nature and environment too. The work of Australian educator Bill Green has been helpful in conceptualising a holistic and ecological vision of 3D literacy” which we have adapted and developed alongside teacher–researchers in the project (Green, 1988; Green & Beavis, 2012).

Introducing 3D literacy and 3D eco-literacy

Bill Green’s influential model of 3D literacy proposes that there are three essential dimensions to literacy pedagogy: operational, cultural, and critical.

1The operational dimension focuses on competence in technical naming, skills, and production in a range of contexts. This dimension connects with ideas about basic literacy skills and functional literacy.

2The cultural dimension refers to competence in relation to real situations with a focus on knowing how to apply and to select from the different cultural forms and practices available to communicate effectively and powerfully in any given situation. This dimension connects with ideas about cultural literacy (Hirsch, 1987), but is intended to be open and inclusive rather than elitist.

3The critical dimension involves learning how these cultural forms and practices are themselves selective, value-laden, ideological, and constrained. Following from an analysis of powerful interests in meaning making, students critique, and transform texts according to alternative interests. This dimension connects with the concept of critical literacy that originates from critical pedagogy and the work of Paulo Freire on education for social justice (Freire, 1970/1995). The relationship of critical literacy to valuing places and recognising environmental justice and actions is an emerging literacy agenda (see Comber, 2015; Green & Beavis; 2012; Nixon, Comber & Cormack, 2007).

Educators might choose to start with any of these dimensions as they are all interlinked and permeable. The value of separating the dimensions is that this draws attention to how literacy pedagogy privileges particular activities and processes (see Morgan and Iki, this issue). Green’s 3D model also raises important questions for literacy in the 21st century: What do we think of as valuable cultural and environmental texts worth sharing as part of a common heritage? Whose cultural and environmental heritage and place dominates? How can we move discussion of literacy pedagogy in schools beyond a narrow focus on the operational dimension of literacy, which can be just as limiting on screen as on paper? How can students have the confidence to experiment with changing and challenging the literacy forms, models, and practices that they are given?

We adapted Green’s 3D model to explicitly reference environment and ecology as well as culture so that the model becomes “operational, enviro-cultural and eco-critical”. Green’s model originally aimed at clarifying literacy in different learning areas and we have found it especially flexible in this respect (Green, 1988). Inevitably, the model is inflected differently in relation to particular contexts and learning areas as indicated below:

1The operational dimension in English refers to the technical features of writing and design such as punctuation or the use of font. An example from Social Sciences would be the naming of geographical features, while in Arts an aspect of operational literacy is an understanding of the colour wheel.

2The enviro-cultural dimension in English refers to learning about how significant enviro-cultural texts represent nature, environments and places such as “Nui Tireni” by Hone Tuwhare (1997, p.88). In Arts this enviro-cultural literacy might be shown in understanding playwright Bruce Mason’s representation of environmental change, whereas in Social Sciences enviro-cultural literacy might focus on knowledge about the environmental issues of a particular place, such as Kiribati.

3The eco-critical dimension for English could involve the critique of the contradictions of a car advert or researching and writing an eco-poem. In Arts it might mean directing a play from an environmental perspective, and in Social Sciences it could mean analysis and response to the political interests invested in environmental policies or places.

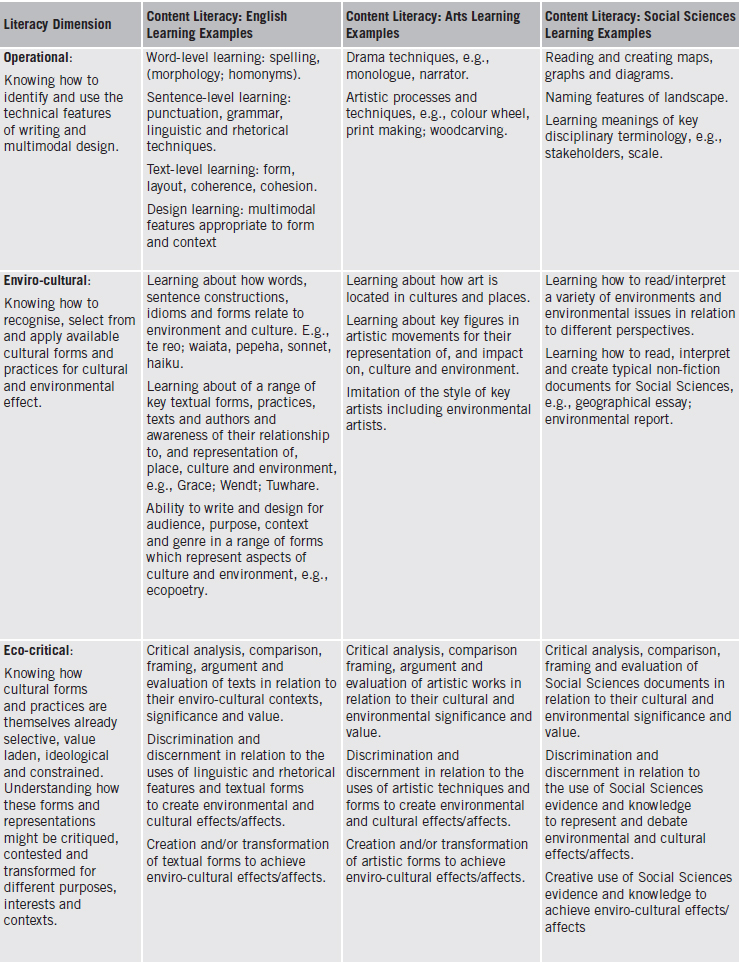

We hope that teachers in other learning areas will see the potential to develop their own approaches to the 3D eco-literacy model. Some further provisional connections to the English, The Arts, and Social Sciences learning areas are outlined in Table 1.

Introducing the project

The project Tuhia ki Te Ao—Write to the Natural World aims to support teachers to develop eco-literacy within their learning areas through attending to the distinctive lenses on the environment offered through different subjects. Six teacher–researchers (three from James Cook High School in Manurewa and three from Hobsonville Point Secondary School in Hobsonville Point) have worked together with researchers to develop ecological themes within 6-week units of work in their learning areas in English, Social Sciences, and The Arts.

What do we think of as valuable cultural and environmental texts worth sharing as part of a common heritage? Whose cultural and environmental heritage and place dominates? How can we move discussion of literacy pedagogy in schools beyond a narrow focus on the operational dimension of literacy, which can be just as limiting on screen as on paper?

TABLE 1. COMPARING 3D ECO-LITERACY IN ENGLISH, THE ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES

In our team we have shared impressions from lesson observations, followed up by detailed written notes, which include the post-lesson evaluative discussion. We have analysed these observations and discussions in relation to the 3D eco-literacy dimensions—operational, enviro-cultural, and eco-critical. Together we have discussed examples of students’ work in each learning area and from two Year 9 classes (ages 13–14) in the two schools. Researchers have then selected from lesson observations, students’ work, and interview data to write “vignettes of practice” and student profiles. These have become important artefacts that we have discussed openly together in order to reflect on the successes and challenges of the lessons within the units of work, and to consider ways of moving the teaching and learning forward. This year we are refining the unit plans and working with two new classes of Year 9 students. We are building more detailed profiles of students’ environmental identities and analysing how these are shaped by the work in the three learning areas.

Introducing the Tuhia ki Te Ao—Write to the Natural World articles

This issue of set discusses work from the exploratory first year of the project. We think it is important to show the initial challenges of reconceptualising literacy from an ecological perspective within the “messiness” of real classrooms. The articles examine the relationship of literacy to learning areas, ecological knowledge, meaning making, and the shaping of environmental identities in two culturally diverse schools. Two articles involve sustained reflection on Māori and Pasifika perspectives on cultural and environmental literacy. We hope that the four articles provide insights into how eco-literacy is applied differently and flexibly in relation to each learning area (see also Sue McDowall’s review of New Zealand literacy research in disciplinary contexts, 2015). Below is a brief summary of each article:

•In English the focus has been on developing a language to speak for nature. The article “Locating Eco-critical Literacy in Secondary English” discusses work in the two schools on reading and writing “eco-poetry”.

•In visual arts, one teacher, Paddy O’Rourke, supported students to connect their cultural and environmental identities with images of place and nature through the concept of whakapapa. In the article “More than Words: Culturally and Environmentally Responsive Literacies in The Arts” this project is discussed with particular reference to Pasifika environmental identities and the culture of the sea and the islands.

•In the article, “I Fear Kiribati will be Gone Forever”: Exploring Eco-literacy in one Social Sciences Classroom”, John Morgan and Maria Iki explain how students at James Cook connected their local and global identities in a powerful project on the problem of sea-level rise in Kiribati.

•Māori literacies have been raised within our team discussions, and in the article “Māori Literacies: Ecological perspectives” we have tried to reflect together on points of connection with the units so far, across both schools.

Throughout these articles we note the strong focus on cultural identity in New Zealand, but suggest that the ecological dimension of this identity could be strengthened through teaching and learning practices that connect students to their environment and places. As David Gruenewald (2008) states, “environmental education in schools is rare and rarely intersects with culturally responsive teaching” (p.144). He suggests that the failure to know about the unique places in our lives is to remain in “a disturbing sort of ignorance” (p.143). More poetically, Wendell Berry writes: “Not knowing where you are, you can lose your soul or your soil, your life or your way home.” (Berry, 1983, p. 103, in Buell, 2001, p.75). The article “Māori Literacies: Ecological perspectives” is a stepping stone for thinking through how eco-literacy connects us to our spiritual souls, our sense of “being”.

The collection of articles on eco-literacy demonstrate that literacy can serve a powerful role in shaping a sense of place and positive environmental attitudes to the world. We want students to be critical readers and producers of powerful texts for, and about, the environment and the natural world. In short, we seek to develop eco-critical literacy practices.

Note

Acknowledgements

John Morgan, Molly Mullen, Rawiri Hindle, and Michelle Johansson are team members of the TLRI funded research project Tuhia ki te Ao–Write to the Natural World.

References

Buell, L. (2001). Writing for an endangered world: Literature, culture, and environment in the U.S. and beyond. Cambridge, MA and London, England: Harvard University Press.

Cope, B. & Kalantzis, M. (Eds). (2000). Multiliteracies: Literacy Learning and the Design of Social Futures. London, England: Routledge.

Comber, B. (2015). Literacy, place and pedagogies of possibility. New York, NY: Routledge.

Ferdman, B. (1990). Literacy and cultural identity. Harvard Educational Review, 60(2), 181–205. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.60.2.k10410245xxw0030

Freire, P. (1995). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Continuum. (Original work published 1970).

Gee, J. P. (2003). What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Green, B. (1988). Subject-specific literacy and school learning: A focus on writing. Australian Journal of Education, (August) 32, 156–179.

Green, B., & Beavis, C. A. (2012). Literacy in 3D: An integrated perspective in theory and practice. Victoria, Australia: ACER Press.

Gruenewald, D. (2008). Place-based education: Grounding culturally responsive teaching in geographical diversity. In D. Gruenewald, & G. Smith, (2008) (Eds.). Place-based education in the global age. New York, NY and Abingdon, England: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Hirsch, E.D. (1987). Cultural literacy: What every American needs to know. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). (2014). Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability [Report]. Retrieved from http://www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/publications_and_data_reports.shtml

Kalantzis, M., & Cope, B. (2012). Literacies. Victoria, Australia: Cambridge University Press.

Louv, R. (2005). Last child in the woods: Saving our children from nature deficit disorder: Chapel Hill, NC: Algonquin Books.

Macfarlane, R. (2015b). Landmarks. London, United Kingdom: Penguin.

McDowall, S. (2015). Literacy research that matters. A review of the school sector and ECE projects. http://www.nzcer.org.nz/research/publications/literacy-research-matters-review-school-sector-and-ece-literacy-projects

Morton, J. (2017). Celebrities, scientists join new nationwide push for action on climate change. In New Zealand Herald, 18th June. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=11878784

Nixon, H., Comber, B., & Cormack, P. (2007). River literacies: Researching in contradictory spaces of cross-disciplinarity and normativity. English Teaching Practice and Critique, 6(3), 92 –111.

Orr, D. W. (2004). Earth in mind: On education, environment, and the human prospect. Washington, ML; London, UK: Island Press.

Tuwhare, H. (1997). Nui tireni (Long white shroud). In Shape-shifter (p.88). Wellington: Steele Roberts.

Sasha Matthewman is a senior lecturer at the University of Auckland and principal investigator on the TLRI-funded research project Tuhia ki Te Ao–Write to the Natural World. She has worked as a teacher of English in a variety of schools and as a teacher educator in the UK and New Zealand. She is the author of Teaching Secondary English as if the Planet Matters (2010).

Sasha Matthewman is a senior lecturer at the University of Auckland and principal investigator on the TLRI-funded research project Tuhia ki Te Ao–Write to the Natural World. She has worked as a teacher of English in a variety of schools and as a teacher educator in the UK and New Zealand. She is the author of Teaching Secondary English as if the Planet Matters (2010).

Email: sr.matthewman@auckland.ac.nz

John Morgan, Molly Mullen, Rawiri Hindle, and Michelle Johansson are University of Auckland members of Tuhia ki Te Ao–Write to the Natural World.

John Morgan, Molly Mullen, Rawiri Hindle, and Michelle Johansson are University of Auckland members of Tuhia ki Te Ao–Write to the Natural World.